Ant Farm: The Media Collective

Description

Week 7: February 27 – March 5

Linking the Chip Lord interview to our study of the integration of the arts and forms of collaboration, we will look in depth at how Ant Farm pioneered the interdisciplinary fusion of media art, performance, spectacle, and sculpture in such iconic works as Media Burn, Cadillac Ranch, and the Eternal Frame. We discuss the historical importance importance of media collectives and experimentation in the 1960s and 1970s.

Assignments

Due in two weeks: March 13 (no class next week, spring recess)

Reading

- Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz, “Welcome to Electronic Café International,” 1992, Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality

- Roy Ascott, “Is There Love in the Telematic Embrace,” 1991, Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality

Works for Class Discussion

- Douglas Davis, World’s Longest Collaborative Sentence, 1984

- Kit Galloway & Sherri Rabinowitz, Hole-in-Space, 1980

Research Critique

Each student will be assigned the following work to research and critique:

- Paul Sermon, artwork: Telematic Dreaming, 1992

Write a short 300 word essay about your assigned work and the artist. Incorporate the readings (see above), as relevant, into your research post, using at least one quote from each of the readings to support your own research and analysis.

The goal of the research critique is to conduct independent research by reviewing the online documentation of the work, visiting the artist’s Website, and googling any other relevant information about the artist and their work. You will give a presentation of your research in class and we will discuss how it relates to the topic of the week: Telematic Art

Here are instructions for the research critique:

- Create a new post on your blog incorporating relevant hyperlinks, images, video, etc

- Be sure to reference and quote from the reading to provide context for your critique

- Apply the “Research” category

- Apply appropriate tags

- Add a featured image

- Post a comment on at least one other research post prior to the following class

- Be sure your post is formatted correctly, is readable, and that all media and quotes are DISCUSSED in the essay, not just used as introductory material.

Be prepared to synthesize and present your summary for class discussion in two weeks.

Outline

Reading and Analysis of the Ant Farm media collective

1968 – 1978

Co-founded by Chip Lord and Doug Michaels, with additional members Hudson Marquez and Curtis Schreier, including several other collaborators on various projects.

Constance Lewallen (2004): Ant Farm (1968-1978), Michael Sorkin, Sex, Drugs, Rock and Roll, Cars, Dolphins, and Architecture, Berkeley: UC Press

Many took to the woods, back to nature, to study communitarianism and to live a life of virtuous simplicity. Others wondered about the architectural equivalent of rock and roll. From this matrix, Ant Farm emerged in… 1968.

Ant Farm was a product of the 1960s in America: rebellion, hippie movement, non-conformist, rock and roll, etc. Out of this ferment they began to create works of architecture, art, performances, and other interdisciplinary forms that signified the stretching of artist boundaries that was in the air of the 1960s with the emergence of video and new media technologies.

It wasn’t just the music that was inspirational; the rock group also emerged as a model of practice for Ant Farm.

Ant Farm as a media collective was part of the communalism of the 1960s, the rock band, and the emphasis on collaboration and collectivity. Ant Farm also stood for the underground, where ants far from our view build colonies and communities.

The group well understood that the object is nothing without its performative aura, and their high-theatric events Media Burn (1975) and The Eternal Frame (1975) were characteristic of their edgy hilarity and deliriously twisted appropriations.

These two works incorporated the interdisciplinary forms of performance, sculpture, video, and media culture to challenge the primacy of television (Media Burn), and the power of the television image as an iconic historical documentation (The Eternal Frame) that shapes our sense of history and reality.

Countercultural bricoleurs, they created a graphic and architectural style that joined the curvaceous enthusiasms and future lust.

Ant Farm also created futuristic architectural forms, such as The House of the Century, which were influenced visionary architects such as Buckminster Fuller, who was the designer of the geodesic dome, used in the Pepsi Pavilion we studied earlier this semester.

The postmodernist architecture that emerged during Ant Farm’s fateful decade represented—inter alia—a post-televisual surreal. Watching television, the most powerful everyday experience of surreality ever devised, was formative of the cultural outlook of anyone growing up in America in the fifties and sixties.

Ant Farm was influenced by growing up on television, the culture of television and its influence on the formative stages of those growing up in the post World War II baby boom. Both Media Burn and the Eternal Frame are directly related to television culture. Media Burn is an attack on television and the power of the broadcast, whereas the Eternal Frame replays the image of President Kennedy’s assassination that was burned into the consciousness of a generation.

They were genuine researchers, and their contribution … set the agenda for contemporary research in environmentalism, advanced building technologies, electronic globalization, public art and space, and postindustrial flows.

Their works explored environmentalism, science, new technologies, public art, etc., such as the Dolphin Embassy, in which they built a vessel in Australia to explore communications with dolphins, to attempt to form a common language.

The Ants’ project grew from a foundational enthusiasm: cars, our national icon.

They were deeply interested in the American car of the 1950s as an icon representation of the American Dream, particularly the tailfin, which led to the creation of Cadillac Ranch in 1974. Chip Lord had a particular fascination for the Cadillac tailfin as a design motif of American futurism, utopianism, desire, seduction and pure style. The essence of the Dream Car in America.

The ultimate countercultural vehicles were Volkswagen vans and converted school buses (e.g., the psychedelic transport of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters), self-effacing but communal vehicles designed to enable the gathering of the tribe, but also, critically, genuinely mobile homes for the realization of the wildest dreams of hippie nomadology.

The Ant Farm created their own Media Van, which was patterned after the bus that was used by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters in 1964 to drive across the US and introduce counter-culturalism to American youth and the post World War II baby boom generation.

Ant Farm’s inflatables—portable, affordable, cut loose from the walls of the academy—were the extension of the car by other means.

Ant Farm’s architectural interests involved the creation of inflatables, temporary structures that could be built cheaply and efficiently as part of their interest in nomadic, portable lifestyle. This too was influenced by the Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome as an alternative lifestyle dwelling that rejected “Brutalist Architecture,” the cold, hard-edged modernist architecture that was popularized by such architects such as Le Corbusier.

Ant Farm’s eternal emblem is Cadillac Ranch (1974), that primal icon of gathering. Its Stonehenge quality precisely suggests the work of a cult willing to go to absurd lengths in worship of an object of totally strange character.

With Cadillac Ranch, Ant Farm realized its vision of the American car as an icon symbol of desire, materialism, futurism, shaping not only the car culture of America, but around the world. Located on Route 66 in Amarillo, Texas, they buried the noses of ten Cadillacs in the ground, Ant Farm proposed Cadillac Ranch as a monument to the rise and fall of the tailfin. It was intended to be a roadside attraction, a readymade (like Duchamp), a symbol of American power and ingenuity turned upside down: a critical assessment that undermines and challenges the shininess of the American Dream, the “the inevitable doom of the entire project of the automobile.”

Ant Farm’s series of car concerts and the Media Burn Phantom Dream Car continued to expand the car’s expressive, self-critical range. A Caddy customized into a hyperconcept car, the Phantom Dream Car was designed to enable a short-lived event symbolizing its own futility (being driven into a flaming wall of televisions) and to mock received futurist fantasies of speed and the glories of mass destruction.

Media Burn is a classic confrontation with the power of television, the symbol of broadcast media, the ubiquitous nature of the image as it is disseminated to our tv sets. This work is a challenge to television, as well as its embrace, since the Phantom Car itself is equipped with an elaborate television monitoring system that guides the “artist-dummies” to their inevitable destructive destination into the burning video wall.

However, Ant Farm’s most biting piece of auto critique, and their most brutally direct mating of form and place, was their reenactment of John F. Kennedy’s assassination at Dealey Plaza in Dallas for The Eternal Frame.

In the The Eternal Frame Ant Farm, in collaboration with another media collective T.R. Uthco, re-enacted the Kennedy assassination. Why you may ask? Perhaps because of the powerful imagery of the Zapruder Film that runs as a narrative through the lives of a generation, in which, like September 11th for another generation, the images holds tremendous power to shape our reality and the impact of the event. In many ways, the images of 9/11, like the images of the Kennedy Assassination, are more powerful than the event itself. With the advent of television, images course through the global nervous system and reside in our consciousness to remain in our memory forever. Perhaps this is the ultimate weapon: the creation of a media spectacle? Both Media Burn and the Eternal Frame are critical, artistic examinations of the media spectacle and the nature of the mediated image.

Architecture, invariably social, was not simply politically but also conceptually fraught during the Ant Farm era.

Although Ant Farm presented itself as an architectural group, they were artists, and though some of their projects of a practical nature, they were always pushing the boundaries of cultural critique and irony. As artists, they were concerned more with modeling IDEAS as a way of challenging American culture, including its architecture, manufacturing, automobiles, media, politics as a form of artistic expression. They incorporated the media of the day (video) in order to challenge the media establishment. And they were by nature social, as a collective of artists, working together, negotiating ideas, committed to the collaborative model of the artist collective that was prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s.

Beginning with their first inflatable projects, Ant Farm rode the wave of political and cultural enthusiasms that sought an architecture that could be realized outside the intentions of the Man.

Returning to the inflatables, they were testing new ideas, such as nomadic culture, in which people were not necessarily rooted to one place, one dwelling, one family, one lifestyle, but they were continuously exploring with curiosity the alternative modes of lifestyle as an experiment in living. Ant Farm ebbed and flowed with members, an evolving extended family of artists who worked on a variety of projects TOGETHER. This was a radical departure from the top-down hierarchical structure of a traditional architectural firm, as well as the artistic process that is generally navigated by a single, solitary artist. Ant Farm was a committed media collective and every project, decision, and execution was done as in the spirit of the collective process.

The dome, recurrent in their work from the inflatables to Convention City (1972) and Freedomland (1973), was a crucial totem of the liberty of undifferentiated enclosures to support free styles of inhabitation.

Convention City (1972) was typical of the prototypical way in which they modeled ideas. Convention City proposed for the 1976 political conventions and bicentennial, was so ambitious as to be more than likely unrealizable but in fact is the kind of visionary thinking that might only come from artists who are not constrained by the practical but perhaps more focused on the conceptual.They envisioned building the “World’s Largest TV Studio” from their earlier intervention at the 1972 political conventions, in which, together with TVTV they conducted guerilla-style interviews and on-site video documentation.

Ant Farm also authored the 1970 Inflatocookbook to share and promulgate both technology and vibe, the pneumatology of freedom. The point wasn’t simply form, but access too.

The Inflatocookbook was a book of “recipes” for inflatables, a do-it-yourself book of ideas and techniques inspired by Stewart Brand’s The Whole Earth Catalog (1968/72), and also coinciding with Radical Software (1970-74), an alternative publication chronicling the rise of the video movement, both of which served the counter-culture as an alternative guide of new technologies and methods for new forms of lifestyle, communalism, and modes of collective living. This was the cultural milieu that the Ant Farm operated in.

Performance, video, public sculpture, architecture, and polemic were all wielded with huge skill and massive aplomb.

From the works mentioned above, it is clear that Ant Farm was dedicated to using whatever materials and forms suited the project, an interdisciplinary approach to architecture and art they helped pioneer. The three works we are studying: Cadillac Ranch, Media Burn, and the Eternal Frame, use these materials and processes to create integrated works of art.

Long live the Ants!

Works for Review

Ant Farm, a group of artists and architects based in San Francisco, produced experimental work between 1968 and 1978. The group combined architecture, performance, happenings, sculpture, installation, and graphic design, and documented its activities on camera in the early days of video art, embracing the latest technologies to disseminate its scathing criticism of American culture and mass media.

Ant Farm was a product of the 1960s in America: rebellion, hippie movement, non-conformist, rock and roll, etc. Out of this ferment they began to create works of architecture, art, performances, and other interdisciplinary forms that signified the stretching of artist boundaries that was in the air of the 1960s with the emergence of video and new media technologies.

Ant Farm as a media collective was part of the communalism of the 1960s, the rock band, and the emphasis on collaboration and collectivity. Ant Farm also stood for the underground, where ants far from our view build colonies and communities.

Ant Farm’s architectural interests involved the creation of inflatables, temporary structures that could be built cheaply and efficiently as part of their interest in nomadic, portable lifestyle.

Ant Farm was influenced by growing up on television, the culture of television and its influence on the formative stages of those growing up in the post World War II baby boom.

Cadillac Ranch (1974)

In 1974 Ant Farm staged Cadillac Ranch Show, its most famous intervention, in Amarillo, Texas, along U.S. Route 66. Ten different models of Cadillac cars were half-buried in a row, nose-first in the ground, at a sixty-degree angle corresponding to that of the Great Pyramid of Giza, in Egypt. Each car features one step in the evolution of the tail fin from 1949 to 1963 in a statement about innovation in a technological era, the American dream, and the absurdity of consumerism. The cars are periodically repainted; they rarely last more than a few hours without new graffiti. The video alternates between footage of the making of the installation and sequences in which members of the group examine each Cadillac in detail, depicting its value as a design object at once wonderful and grotesque and as an expression of the values of American society.

They were deeply interested in the American car of the 1950s as an icon representation of the American Dream, particularly the tailfin, which led to the creation of Cadillac Ranch in 1974. Chip Lord had a particular fascination for the Cadillac tailfin as a design motif of American futurism, utopianism, desire, seduction and pure style. The essence of the Dream Car in America.

With Cadillac Ranch, Ant Farm realized its vision of the American car as an icon symbol of desire, materialism, futurism, shaping not only the car culture of America, but around the world. Located on Route 66 in Amarillo, Texas, they buried the noses of ten Cadillacs in the ground, Ant Farm proposed Cadillac Ranch as a monument to the rise and fall of the tailfin. It was intended to be a roadside attraction, a readymade (like Duchamp), a symbol of American power and ingenuity turned upside down: a critical assessment that undermines and challenges the shininess of the American Dream, the “the inevitable doom of the entire project of the automobile.”

Media Burn (1975)

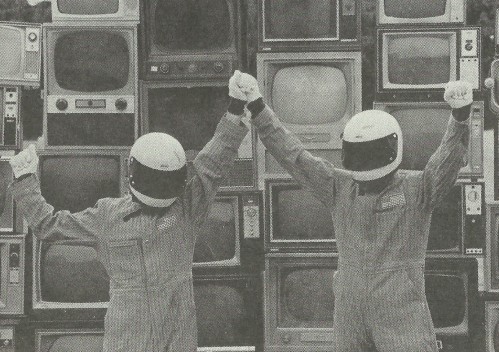

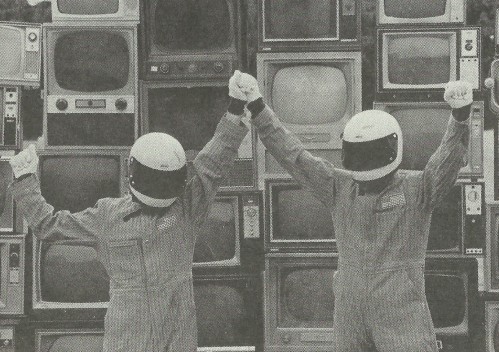

Media Burn integrates performance, spectacle and media critique, as Ant Farm stages an explosive collision of two of America’s most potent cultural symbols: the automobile and television. On July 4, 1975, at San Francisco’s Cow Palace, Ant Farm presented what they termed the “ultimate media event.” In this alternative Bicentennial celebration, a “Phantom Dream Car”—a reconstructed 1959 El Dorado Cadillac convertible—was driven through a wall of burning TV sets.

Footage of the actual event, much of which was shot from a closed-circuit video camera mounted inside a customized tail-fin, is framed and juxtaposed with news coverage by the local television stations. Doug Hall, introduced as John F. Kennedy, assumes the role of the Artist-President to deliver a speech about the impact of mass media monopolies on American life: “Who can deny that we are a nation addicted to television and the constant flow of media? Haven’t you ever wanted to put your foot through your television?”

The spectacle of the Cadillac crashing through the burning TV sets became a visual manifesto of the early alternative video movement, an emblem of an oppositional and irreverent stance against the political and cultural imperatives promoted by television, and the passivity of TV viewing.

Examining the impact of mass media in American culture, Media Burn exemplifies Ant Farm’s fascination with the automobile and television as cultural artifacts, and their approach to social critique through spectacle and humor.

Ant Farm organized Media Burn, in which two “artist dummies” dressed as astronauts “drove” a customized 1959 Cadillac renamed the Phantom Dream Car at full speed into a wall of flaming television sets. Using the car once again as a cultural icon, Ant Farm addressed the pervasive presence of television in everyday life, affronting the same media they had invited to cover the event. The video is styled after news coverage of a space launch, including melodramatic pre-stunt interviews with the members of the group and an inspirational speech by a John F. Kennedy impersonator.

The following words were spoken by the Artist-President, performed by Doug Hall. This statement speaks to the power of the mediated image, forecasting the effect of 9/11.

“The world may never understand what was done here today, but the image created here shall never be forgotten.”

Media Burn is a classic confrontation with the power of television, the symbol of broadcast media, the ubiquitous nature of the image as it is disseminated to our tv sets.

Ant Farm’s series of car concerts and the Media Burn Phantom Dream Car continued to expand the car’s expressive, self-critical range. A Caddy customized into a hyperconcept car, the Phantom Dream Car was designed to enable a short-lived event symbolizing its own futility (being driven into a flaming wall of televisions) and to mock received futurist fantasies of speed and the glories of mass destruction.

This work is a challenge to television, as well as its embrace, since the Phantom Car itself is equipped with an elaborate television monitoring system that guides the “artist-dummies” to their inevitable destructive destination into the burning video wall.

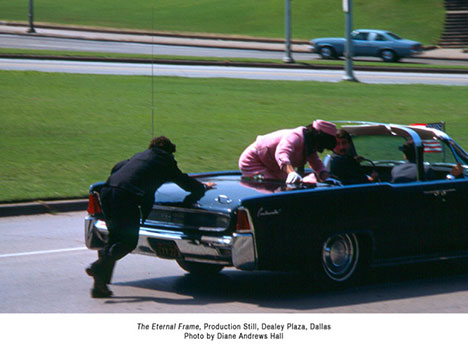

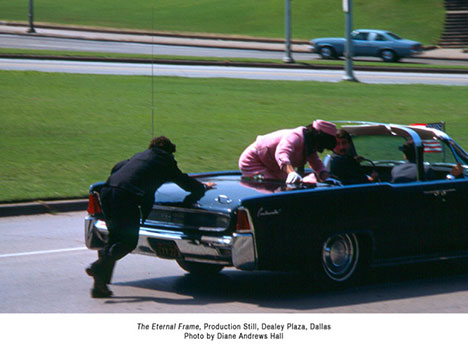

The Eternal Frame (1975)

The Eternal Frame is an examination of the role that the media plays in the creation of (post)modern historical myths. A collaboration of T.R. Uthco and Ant Farm, the iconic event that signified the ultimate collusion of historical spectacle and media image was the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963. The work begins with an excerpt from one of the most iconic and significant film documents of the twentieth century: Super-8 footage of the Kennedy assassination shot by Abraham Zapruder, a bystander on the parade route, which is one of the very few filmic records of the event.

Using those infamous few frames of film as their starting point, T.R. Uthco and Ant Farm construct a multilevelled event that is simultaneously a live performance spectacle, a taped re-enactment of the assassination, a mock documentary, and, perhaps most insidiously, a simulation of the Zapruder film itself. Performed in Dealey Plaza in Dallas — the actual site of the assassination — the re-enactment elicits bizarre responses from the spectators, who react to the simulation as though it were the original event.

The grotesque juxtaposition of circus and tragedy calls our media “experience” and collective memory of the actual event into question. The gulf between reality and image is foregrounded by the manifest devices of Doug Hall’s impersonation of Kennedy and Michel’s drag transformation into Jacqueline Kennedy. Hall, in his role as the Artist-President, addresses his audience with the ironic observation that “I am, in reality, only another image on your screen.”

In the uncanny simulation of the Zapruder film, however, the impersonations are not as apparent, raising the question of the veracity of the image. Image and reality collide in a post-assassination interview; while both President Kennedy and the imagic Artist-President are dead and entered into myth, Hall discusses his role like an actor having completed a film.

Through a deconstruction of the filmic image, the artists underscore the media’s importance to contemporary mythology — in which greatness is more a measure of drama than substance — and the extent to which it can be manipulated. In light of television’s transformation of the American political system — and the later election of a movie star to the presidency — The Eternal Frame continues to ring a truthful and haunting chord in the American consciousness.

In the The Eternal Frame Ant Farm, in collaboration with another media collective T.R. Uthoco, re-enacted the Kennedy assassination.

Why you may ask? Perhaps because of the powerful imagery of the Zapruder Film that runs as a narrative through the lives of a generation, in which, like September 11th for another generation, the images holds tremendous power to shape our reality and the impact of the event. In many ways, the images of 9/11, like the images of the Kennedy Assassination, are more powerful than the event itself.

With the advent of television, images course through the global nervous system and reside in our consciousness to remain in our memory forever. Perhaps this is the ultimate weapon: the creation of a media spectacle? Both Media Burn and the Eternal Frame are critical, artistic examinations of the media spectacle and the nature of the mediated image.

Long Live the Ants!