Week 2 – Open Source / Open Culture

Description

Open Source

Thinking

Culture

Movement

- Knowledge should be spread freely

- Growth should come from developing, altering or enriching already existing works

- Have equal access to information

Readings:

The Open Source Definition

https://opensource.org/osd

All Together Now: Artists and Crowdsourcing

http://www.artnews.com/2014/09/02/artists-and-crowdsourcing/

How Open Source Is Disrupting Visual Art

https://creators.vice.com/en_us/article/wnzm4q/how-open-source-is-disrupting-visual-art

Meet the Artist Building an Open-Source Database of Everyday Movements

https://creators.vice.com/en_au/article/nz4aeg/archiving-socio-economic-diversity-east-london-movement

Artists/Artworks:

Craig D. Giffen, Human Clock (2001 – ongoing)

Ed Forniels, Dorm Daze (2011)

Lauren McCarthy, Social Turkers (2013), p5.js

Kyle McDonalds, Faces (2011 – on-going), FaceOSC

James George, slyPhone, DepthEditorDebug

Keywords:

Do-it-with-others (DIWO), peer2peer, co-creation, sharing, community, collaboration, contributing, crowdsourcing

Outline

Open Source

(Courtesy Randall Packer)

Let’s begin with a discussion of open source thinking and its practices with some specific examples. Open source has a long history and we will discuss it in detail in connection with the readings below.

First, here is an artwork by Nathaniel Stern and Scott Kildall called Wikipedia Art. Here is a short video trailer of the project:

“A collaborative project initiated with Scott Kildall, Wikipedia Art was originally intended to be art composed on Wikipedia, and thus art that anyone can edit. Since the work itself manifested as a conventional Wikipedia page, would-be art editors were required to follow Wikipedia’s enforced standards of quality and verifiability; any changes to the art had to be published on, and cited from, ‘credible’ external sources: interviews, blogs, or articles in ‘trustworthy’ media institutions, which would birth and then slowly transform what the work is and does and means simply through their writing and talking about it. Wikipedia Art, we asserted at its creation, may start as an intervention, turn into an object, die and be resurrected, etc, through a creative pattern / feedback loop of publish-cite-transform that we called “performative citations.” Despite its live mutations through continuous streams of press online, Wikipedia Art was considered controversial by those in the Wikipedia community, and removed from the site 15 hours after its birth. But the debate and discussion there, and later in the art blogosphere and mainstream press, produced a notable work after all. Various communities still “transform what the work is and does and means simply through their writing and talking about it,” despite its absence from Wikipedia. The “work” has since lived as a myriad of substantiated remixes at the Venice Biennale, a performance in New York City, a book chapter, several real-world installations in Berlin, London, and Vancouver, and more. It continues to question epistemological and material occurrence in the Communication and Information Ages.” – from the project Web page

The Wikipedia Art project challenges the authenticity of open source practices, such as Wikipedia, where believe information to be verified and true with citations and references. However, how do we really know if those citations are true, much as how do we know if the news we read on social media is fake?

Thus, a group of artists created a Wikipedia page as an art project to test the idea of open sourced authenticity, by requiring that anyone who contributes to the Wikipedia Art page to produce citations, or what they called “performative citations.”

This project questions whether or not we can trust online information. Do you believe everything you read, even when it is supposed to be true, such as Wikipedia? Does open source expand our ability to create and document knowledge, or does it open the door to misinformation. This is an important question we must ask in regards to our study of open source thinking.

Related Reading:

(1) Vaidhyanathan, Sida (2005) “Open Source as Culture-Culture as Open Source,” The Social Media Reader. New York: New York University Press, 2012

Some questions concerning open source ideology to consider:

- Why do we think of open source as “utopian,” “free-spirited,” “anarchic,” or even “impracticable?” What is the fear of open source in an economically-driven society that values and protects proprietary methods?

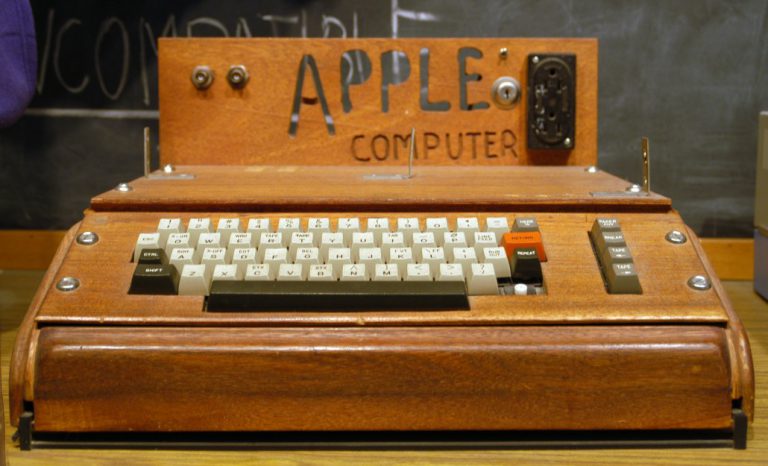

- What was the impact of Bill Gates’ decision to “sell” software in 1976, when up until that time it was strictly the domain of hackers and software enthusiasts and hobbyists who wrote software purely for purposes of sharing and trading.

“Strong intellectual property rights inefficiently shrink the universe of existing information inputs that can be subject to this [software development] process.”

“Regulators concerned with fostering innovation may better direct their efforts toward providing the institutional tools that would help thousands of people to collaborate.”

– Yochai Benkler, Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies at Harvard Law School

- How might proprietary or “elite” control of technology be limiting or constraining to development and innovation?

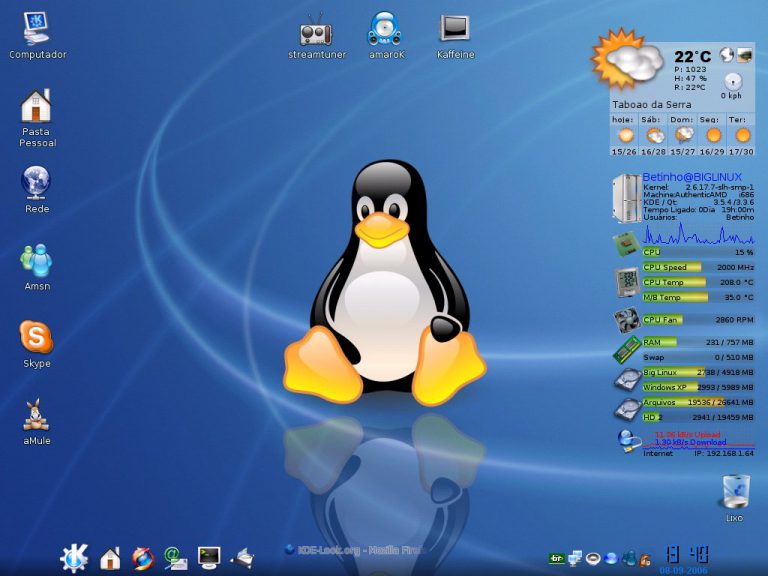

- What does the emergence of “peer-production” hardware/software such as the World Wide Web or Wikipedia or Linux tell us about the power of open source ideology? And what is meant by “peer-production?”

- What is “open source journalism” and what are the implications of participating in the global information ecosystem?

“Creativity as a social process is the common denominator… the act of creation is a social act… a node in a network of relations.” – Vladimir Hafstein, associate professor of folkloristics and ethnology at the University of Iceland

- How do the concepts and ideologies of open source thinking impact and shape our study and creation of art?

- How might OSS serve as a platform for peer production that will help catalyze our work, both collectively and individually?

Related Reading:

Randall Packer (2015). “The Studio of Now,” “The Way of Open Source,“ and “The Open Source Artist” from the Open Source Studio essay.

“Creativity as a social process is the common denominator… the act of creation is a social act… a node in a network of relations.” – Vladimir Hafstein, associate professor of folkloristics and ethnology at the University of Iceland

Review the article and its references.

Some questions concerning open source ideology to consider:

- Why is the act of creation a social act, rather than a solitary one? In other words, how is art a social activity?

- Why do we think of open source as “utopian,” “free-spirited,” “anarchic,” “risky” or even “impracticable?” What is the fear of open source in an economically-driven society that values and protects proprietary methods?

- How do the concepts and ideologies of open source thinking impact and shape our study and creation of art? For example, what about sharing one’s work such as Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater. How does this practice correlate with social media?

- How is OSS, based on open source thinking, a collaborative medium? How does it change the paradigm of how work is created for a studio art class?

Works for Review: The Open Source Artist

How do artists use techniques of appropriation to create collage work with electronic media:

- Nam June Paik, Global Groove (1973)

‘This is a glimpse of a video landscape of tomorrow when you will be able to switch on any TV station on the earth and TV guides will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book.’ Paik’s introductory statement stands for the tape’s compositional principle and message – global channel zapping, in 1973 a visionary precursor of subsequent developments. The spirit of the tape conveys Marshall McLuhan’s theory of a future ‘global village’, which Paik matched with an idea of his own: ‘If we could compile a weekly TV festival made up of music and dance from every county, and distributed it free-of-charge round the world via the proposed common video market, it would have a phenomenal effect on education and entertainment.’ A typical Paik mixture, the tape includes excerpts from TV programmes, contributions by artist friends such as John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, Charlotte Moorman and Karlheinz Stockhausen, footage by other video artists like Jud Yalkut and Robert Breer, and excerpts from earlier Paik videos. The combination of mass media and avant-garde was aimed at art-lovers and ‘normal’ TV viewers alike. The video was broadcast by WNET-TV on 30 January 1974. – from http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/global-grove/

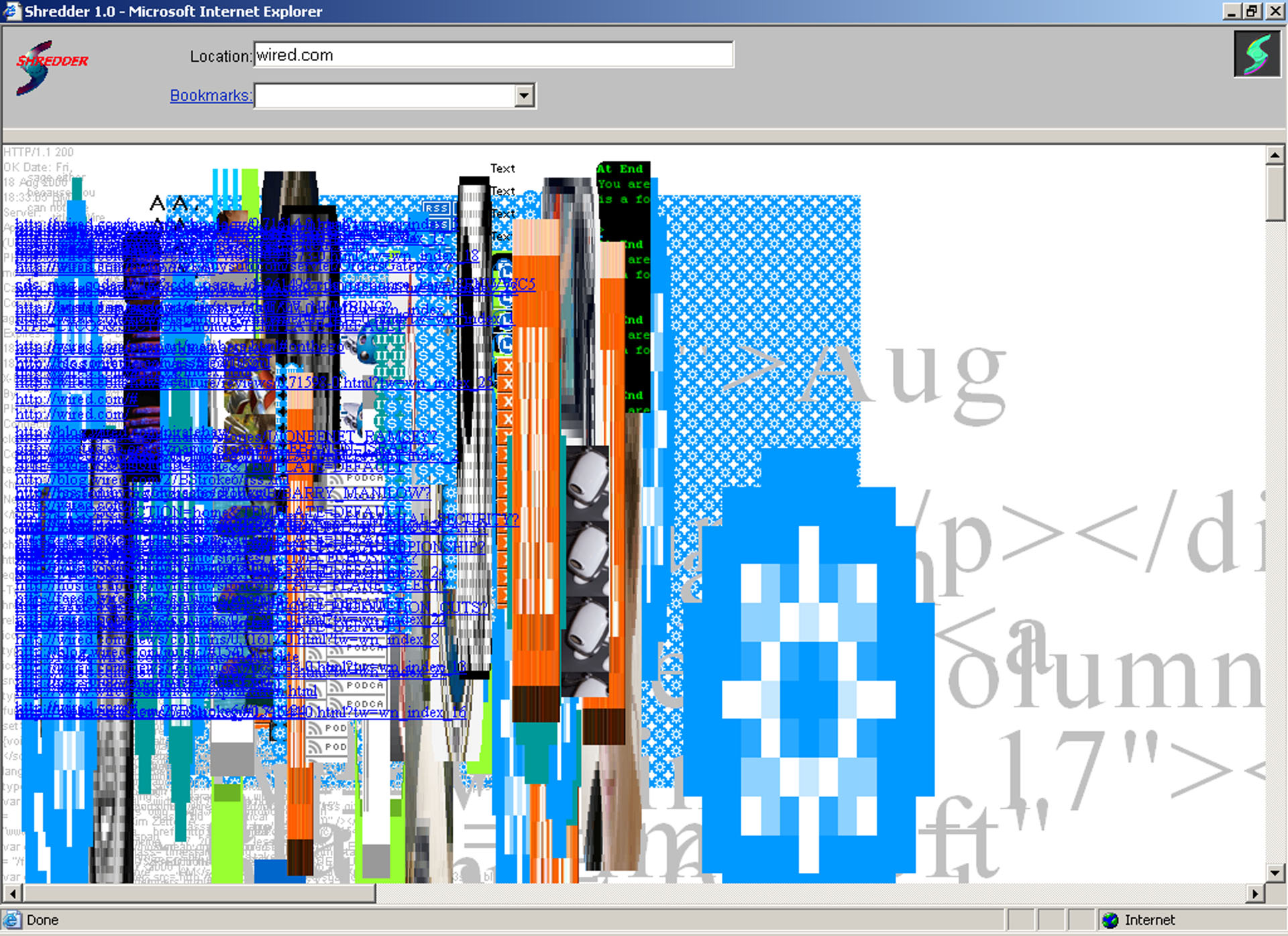

- Mark Napier, The Shredder (1998)

In Mark Napier’s The Shredder, the artist designed a custom browser that deconstructs or “shreds” Websites, providing the viewer the means to appropriate and generate their own collaged abstraction using the Web as a vast open source repository. The artist has essentially created a tool that resituates the viewer as the protagonist for real-time appropriation. What does this appropriation, remix, and collage reveal about the nature of the Web?

- Craig D. Giffen, The Human Clock (2001-ongoing)

Humanclock.com by Craig D. Giffen shows a photograph or video (contributed by online submissions) with the current time represented somewhere in it. The photo/video changes every minute (all 1,440 occurring minutes on Earth!), thus you end up with a rotating picture clock sorta deal. -from project Webpage

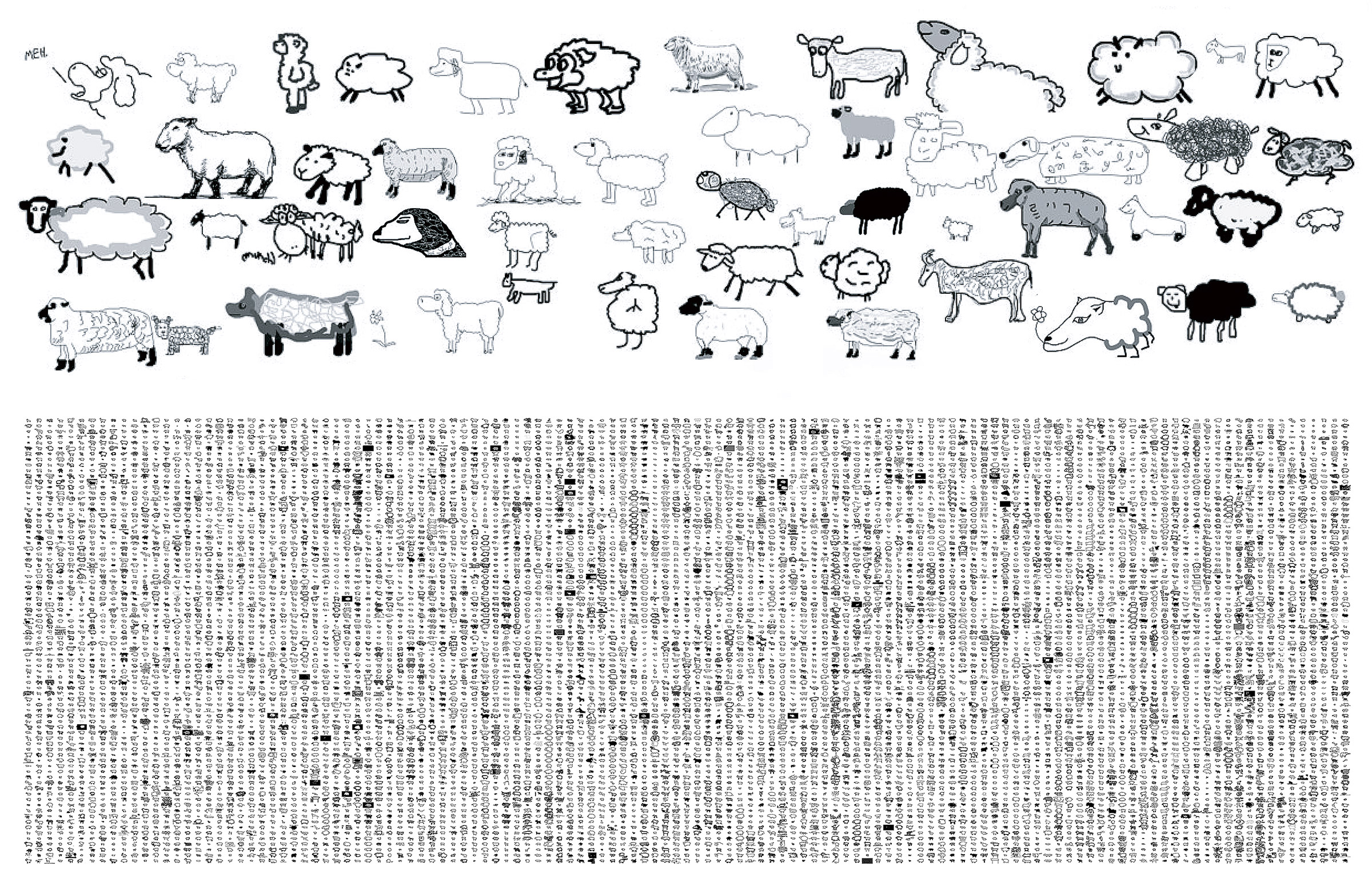

- Aaron Koblin, The Sheep Market (2006)

One of his most famous works, The Sheep Market, used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk data-outsourcing service, which enables online users to contribute a tiny part of a large project for very little compensation. They work in isolation from one another and have little knowledge of what the larger finished product will be.

Koblin asked workers to “draw a sheep facing left” and paid two cents for each one. Over 40 days, 7,600 people drew 10,000 sheep, from which Koblin created a black-and-white mosaic of tiny animals. When one speck in the big picture is selected, it emerges as an individual drawing and you can see an animation of the actual drawing process.

“My hope was . . . to express the individuals within the vast dataset,” says Koblin, “to juxtapose the humanity of an individual process with a gigantic, alienated system. There is so much humanity online, but it exists in such a visually sterile form.”

Koblin’s goal is to change that. As he explains, “An interface can be a powerful narrative device, and as we collect more and more personally and socially relevant data, we have an opportunity, maybe even an obligation, to maintain the humanity and tell some amazing stories as we explore and collaborate together.”

- Lauren McCarthy, Social Turkers: Crowdsourced Dating

What if we could receive real-time feedback on our social interactions? Would unbiased third party monitors be better suited to interpret situations and make decisions for the parties involved? How might augmenting our experience help us become more aware in our relationships, shift us out of normal patterns, and open us to unexpected possibilities? I am developing a system like this for myself using Amazon Mechanical Turk. During a series of dates with new people I meet on the internet, I will stream the interaction to the web using an iPhone app. Turk workers will be paid to watch the stream, interpret what is happening, and offer feedback as to what I should do or say next. This feedback will be communicated to me via text message. – from http://socialturkers.com/

In our globally connected world, is it useful for artists to open up their work and process to an online audience? How so?