Link to slides here.

There are 8 posts filed in Project Development and Planning (this is page 1 of 1).

Machiko Kusahara is an internationally recognized researcher in media art and theory, who has been publishing and curating in the interdisciplinary field connecting art, science, technology, culture, sociology and history. She is given Ph.D in engineering from University of Tokyo for her theoretical research in this field.

Kusahara’s dialogue “From the Movie Screen to Moving Screens: Life in Tokyo with Moving Images” was a reflection and observation of the use of screens in the public space in Japan. The talk focuses on the functions and the social impact of screens, using various examples with different applications of screens to create an interactive media.

Kusahara also highlighted the fact that audiences were often fascinated by screens that were interactive. That brings us to the daily life of an average Japanese white/blue collar where the majority of their time was spent commuting on public transport such as trains. The commute time often accompanied by the use of mobile phones to play games or videos was a source of entertainment for themselves. Screens, being a driving force in Japan, could often be found on the train as well, whether they are used for advertising purposes or for public service announcements.

In recent years, urban public screens have also emerged on the exterior of buildings, as large-scale projections on several architectures, on billboards, and also on moving vehicles. The ad trucks are one of many ways to show how screens have evolved in transmitting information to passers-by.

Ad trucks:

Kusahara shared in her dialogue several examples of how screens were taken to the next level by having them paired with interactivity to engage more public involvement. Major advertising companies have came up with innovative ways to encourage the crowd participation with their ads.

From mobile screen to the big screen:

In Adidas’ “The Highest Goal”, crowds were given the chance to directly interact with the display on public screens from their own mobile phone screens.

From computer/mobile phone screen to projection:

As part of a launch for the Xbox360 game “Blue Dragon”, IMG SRC inc. made shadow projections of dragons at a carpark in Shibuya where the crowd was able to be part of the screen. People could also participate from the official website and they could control the movement of their shadows shown in Shibuya from anywhere around the world.

Kusahara made a comparison between olden-day public screens in Asia and in the U.S. Outdoor cinemas in Asia were held in a way where viewers were sharing public space while for the drive-in theaters in the US, movie-goers are still confined within the private space of their vehicles despite being parked in a public space.

However, both cinemas were lacking in audience participation. Traditional screens was not enough to attract the public’s attention. Screens needed to be transformed and made interactive to encourage crowd involvement. In order for interactivity to come in play on screens, the content needs to be participatory and have transmedia capabilities.

Wayang Kulit:

Wayang Pacak:

Community Television:

Projection Mapping on the National Museum:

SMRT North-South Line Display Panels:

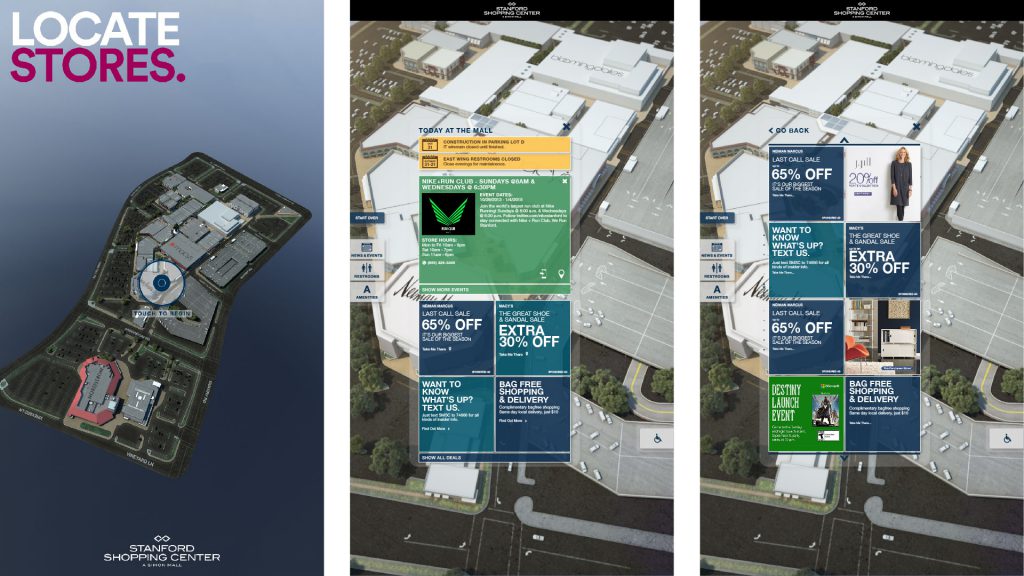

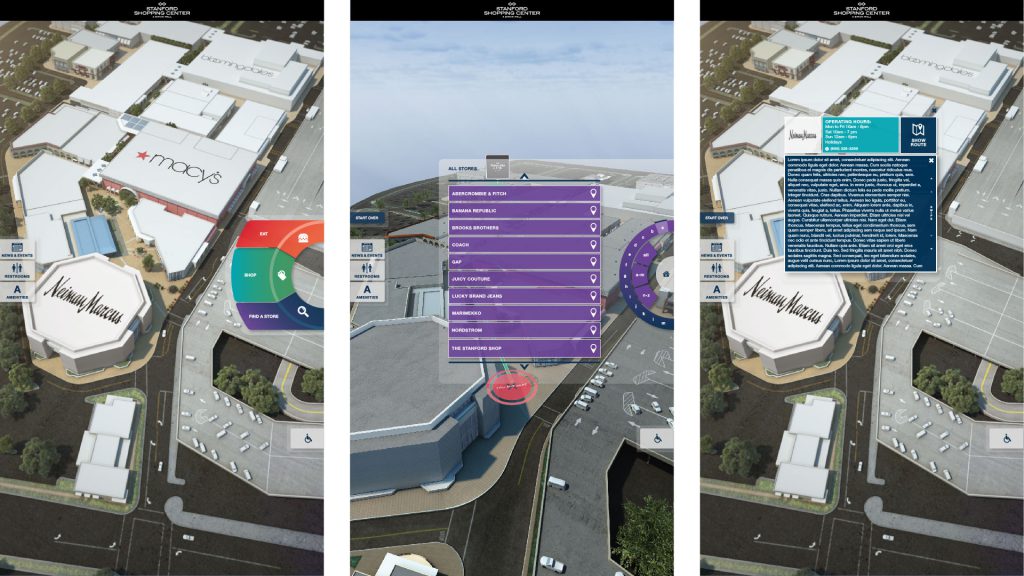

Interactive Mall Directory:

Augmented Reality Photo Booth:

Three Great Light Shows:

The projects shared in Kusahara’s presentation all happened in the last 15 years. Screens have been transformed and have served different purposes for the public. If we could achieve so much in the advancements of screens, could you imagine what have yet to emerge from the next 15 years?

AR contact lenses and hologram models are just one of the few possibilities in the transformation of screens. With developers already working on such ideas, future feats in public screens are endless.

Done by: Goh Cher See & Anam Musta’ein

Driven by his passion in theater, Matt Adams has incorporated performance and interactivity in his projects, exploring sociopolitical themes while applying new and unorthodox methods. Merging the realms between the real world and the virtual, Adams has certainly redefined the genre of play within itself.

Adams began his talk by claiming that when a work is interactive, it means that it is also unfinished. He highlighted the importance for us to see the relation between the two words. When a work is interactive, it means that it leaves and offers something opened for the viewers or participants to come and engage with, and complete for themselves. The viewers are the ones completing the experience for themselves and in turn become a part of the artwork or installation. That is why it is the artist’s responsibility to ensure that the work is tidied up into a narrative to be properly presented to the viewers.

The idea of having a work ‘unfinished’ is pretty evident in all of Blast Theory’s projects that Adams shared during the talk. The participants and their experience play an integral part in making these projects complete.

One project that really stood out for me during the talk was Kidnap (1998), a performance that featured two participants kidnapped in a safe house for 48 hours under the surveillance of several online viewers. The online viewers were given the autonomy to control the cameras in the cell and communicate live with the kidnappers.

Prior to the kidnapping, a registration was posted online to call out for interested participants to partake in the project, which also required them to pay £10 and sign a disclaimer to confirm their consent. Ten entrants were then picked at random to be under surveillance, where their behaviours and daily activities were closely monitored by the team over a two week period. Two of the ten shortlisted participants, Debra and Russell, were then randomly picked again as winners to be involved in the actual kidnapping while keeping law enforcement, friends, and family informed of the situation.

The team was then engaged in a lengthy chase to capture both winners and have them confined in a purpose built room at a secret location where live footage of them were streamed to the online viewers. Over the 48 hours, the winners were fed and taken care of by their kidnappers while the process was monitored by a psychologist. The winners were also offered a prize of £500 if they managed to escape, reach a telephone and call a designated number.

The project was covered by several news reporters across London and was also turned into a 30-minute film which was then premiered at The Green Room in Manchester in September 1998. It managed to garner a major response from the public as it raised the awareness of several social issues circulating the area.

The project was a work of control and consent, inspired by the Spanner Trials where sadomasochists were prosecuted despite carrying out activities out of consent, has also delved into themes that revolved around several other social issues. It exposed the workings of the media in Britain while addressing problems in lottery culture (similar to how participants had to pay a certain sum with a small chance of being awarded a prize money), and voyeurism (where online viewers were able to “spy” on the kidnapped participants in private).

Kidnap is a perfect example to demonstrate how the interactive work was completed by not only the kidnapped winners, but also the online viewers who have spectated the events that transpired over the course of 48 hours with having a certain amount of control to what they were seeing on the screens. The experience was different for the winners as they were physically confined in the space and in the center of attention while the participation of the online viewers were rather more passive. Therefore the work goes unfinished if the participants were taken out of the picture.

“Interactive = Agency

Interactive = Political”

Before ending the talk, Adams also made relations between interactivity with agency and how it is political. Works should have agency for narratives to unfold and different actions may result in different outcomes. It goes the same for how interactive works can be regarded as political, in which it is able to offer a new perspective to spectators or provide change to how certain things should be carried out.

“Every design is a change of our life world; the designer influences our overall experience of the world as a pleasant or ugly place to spend out lives in.”

Thoughtful Interaction Design, while heavy and complex in its content, provides a comprehensive and extensive guide to good design approaches without compromising the responsibilities of the designer upon execution. One of the most important points that was consistently brought up in the reading was the impact that a particular design may have on the user’s end. Designers, either working individually or in a team, needs to be able to see themselves as a material of the design itself. Every aspect of the design process, which includes the resources, and the situation at hand, will ultimately affect the end-users and therefore, has to be thought out carefully. It is vital that designers keep in mind that they have been given the power to influence the lives of others as well as the existing conditions of a premise.

One example of a work that I feel has been successful in its application of thoughtful interaction design is the Connected Mall by Simon Property Group and eBay inc.. The company that aimed to enhance the digital shopping experience came up with an interactive mall directory that allows shoppers to navigate their way around the mall and assist them in making informed shopping decisions.

Connected Mall is a high def six-foot LCD touch screen distributed sparsely inside the mall at the convenience of all shoppers. It includes 3D maps of every floor in the building that maps out directions to every store to ensure that shoppers not only receive a wholesome experience in the mall, but also optimize their shopping efficiency. The touch screen is made adjustable in height, allowing easy access for children, and wheelchair-bound shoppers.

Alternatively, shoppers could also access Connected Mall through an app on their mobile phones. This enables them to refer to the mall directory at any location within and beyond the perimeters of the mall. In terms of its interface, what can be seen on the big LCD touch screens are also displayed in a miniature version of the map on the shoppers’ mobile phones. With the existing installation of Connected Mall in Stanford Shopping Center, it has been proven to ease the user’s shopping experience.

Screen-captures of mobile app:

Here is a video to show how the interface looks like:

Connected Mall has definitely gone through thorough consideration in the design process while developing the application. They have successfully came up with a product that not only pushed retail technology a step further, but managed to find a solution with the challenges of navigating around a huge mall. It is evident that they have applied thoughtful interaction design here.

This reading assignment has definitely redefined my perspective on design. Kim Goodwin highlighted a very important point that separates the idea of being an artist and being a designer. An artist is one who creates to display their vision in the en-product,whether it is a narrative, a form of expression, or an avenue for exploration in the artist’s point of view. Whereas a designer would keep in mind that he or she creates to fulfill a purpose, whether it is in the functionality of the end-product, to serve as a solution to problems, to meet the demands of the client they are working for, or to satisfy the needs and goals of the user of the product or service.

Goodwin has also covered the skeleton and workflow in design by touching on several examples, such as interactivity and experience, to help readers understand how it all works, and how we as designers should go about before jumping in to execute our ideas. I find myself prioritizing aesthetics more than function when it comes down to thinking about designing a particular product. However, I often neglect an important aspect of design itself and that is the user that I am making the design for. As artists, we do get carried away with the beauty of our works that we sometimes disregard the purpose of why we even come up with the work itself. Goodwin’s breakdown of the Goal-Directed Design, a user-centered methodology by Alan Cooper, made me realize the key elements to pay attention to in every step of the workflow.

Goal-Directed Design consists of four different components: principles, patterns, process, and practices. This serves as a framework and a guideline for design teams and companies to follow to ensure that they are able to translate the demands of their clients into designs that meet their needs and satisfaction. Goodwin mentioned how we as designers should think of principles as the rule of grammar in design (creating a good solution), while patterns as the designer’s vocabulary (types of solution that could be useful). However, Goodwin was more focused in explaining the two latter components.

Goal-directed process was dissected into so many more layers that carries more weight in design. He highlighted the importance of personas, where user profiling is crucial in order for a designer to truly understand what their clients really need and from there, make better design decisions. Goodwin also discussed how practices is essential where project planning and consistent communication within the team and with the clients play a huge role in achieving better design.

I have yet to implement this set of rules that were discussed in Goodwin’s writing. I could clearly see how the information that I have gained from the reading could make better improvements to my work and attitude as a designer.

Questions:

1. Is the goal-directed design methodology applicable across all the different disciplines in design itself?

2. How do we as designers go about if we ever lacked in personas?

Stills from Making Chinatown (http://www.mingwong.org/making-chinatown)

Stills from Making Chinatown (http://www.mingwong.org/making-chinatown)

By: Joan Li, Tiffany Anne Rosete & Anam Musta’ein

References

http://artradarjournal.com/2017/05/22/singaporean-artist-sarah-choo-jing-venice-loop-fair-interview/

http://www.sindie.sg/2017/11/stop10-nov-2017-making-chinatown-by.html

“Tue Greenfort, Tamoya Ohboya, 2017.”

Stepping into The Oceanic exhibition at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, the Tamoya Ohboya, an installation by Tue Greenfort, caught my attention. The neon cyan light that glows beyond its display with the very organism that the piece was named after, hovering and floating inside the aquarium was a visual ecstasy. It exposed me to the feeling of calmness yet a certain degree restrain as it immerses its viewers into an artificial habitat.

The Tamoya Ohboya is a species of box jellyfish that is native to the waters of the Dutch Caribbean islands. The species have been in existence for over 500 million years, and thrives only in ideal temperatures and water conditions. Due to the warming of the ocean’s temperatures, researches have observed an increase in the migration of these organisms to new geographical waters.

Greenfort, a Danish artist mostly known for his works revolving around the themes of ecology and the environment, delved into replicating the ideal habitual conditions to sustain the Tamoya Ohboya. By combining art and technology, he was able to create an artificial habitat for these jellyfishes with a tank that was designed to closely resemble the ocean, and devices that maintains and regulates the perfect temperature. This piece was a response to how the environment is changing and proposes a way we, as humans and as a community, could take to preserve delicate life-forms like the Tamoya Ohboya from dying out due to years of destructive human interventions with nature. The concept ties in well with other pieces in the exhibition that urges environmental and economic issues.

Although I find the work compelling in its ways of creating awareness to the mass while highlighting the importance of conserving the environment and how it correlates to the human society, stripping the jellyfishes off its natural habitat and confining it in a small aquarium in the name of art is not an appropriate measure to take. Greenfort’s attempt to display these creatures could be seen as an adverse response to the problem itself rather than the message that he initially intended to tell.

But is there an ethical issue here that needs to be straightened out when it comes to having works like this publicly displayed? Was it necessary for the artist to take live specimens of the creature itself to bring across a message? With the concept of tapu being discussed in the lectures and how we are very informed that there are certain rules and prohibitions practiced in the Polynesian culture concerning the conservation of the very home we live in, are we really protecting the environment? Or is this just another evidence that we are simply causing more harm to it?