Social Broadcasting: An Unfinished Communications Revolution. This is the theme of the symposium, and a phrase saturated with meaning. As quoted by Packer,

Gene Youngblood signals the need for “a communications revolution… an alternative social world” that decentralises the experience of the live broadcast through the creative work of collaborative communities’. (link)

And yet, this complete upheaval of the way we communicate is still “unfinished”. The symposium thus explores this notion of networked communication as a way to open the way to that new world order.

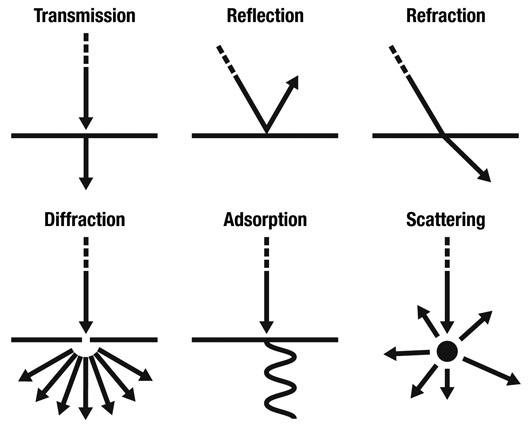

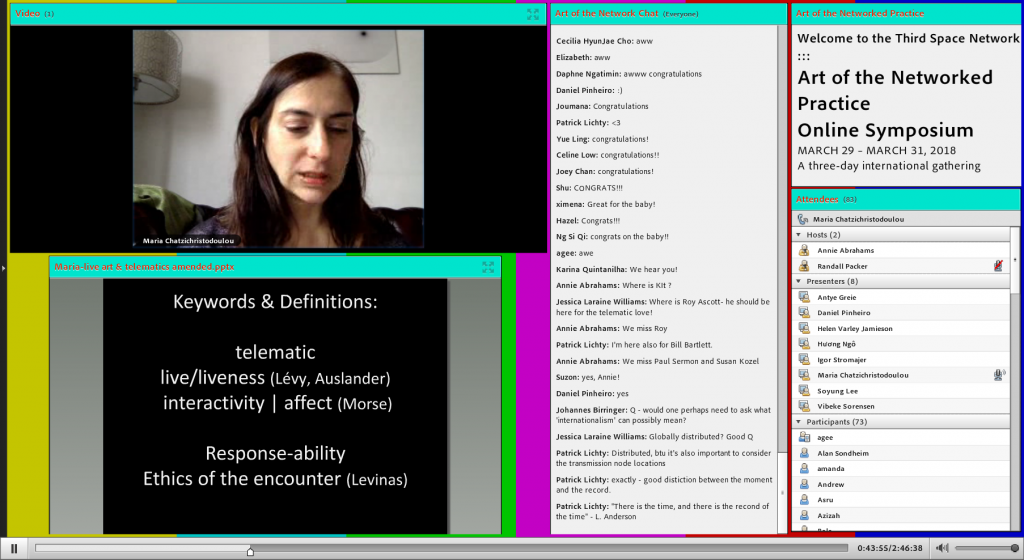

To understand how the social broadcast is revolutionary, we must first understand the live broadcast. Loosely, it is defined as media which is broadcast without a significant delay. The most primitive forms of broadcast would include one-way transmissions, such as with television. However, as Chatzichristodolou (note: will be referred to as Maria X for convenience) states in her keynote, there is another definition of “liveness”, that of something which is “infinitely open to interaction, transformation and connection”. This is a concept which has led the broadcast onto a completely new path, continuously reshaping the “broadcast” into something much more communal, allowing for communication between, than merely to, people.

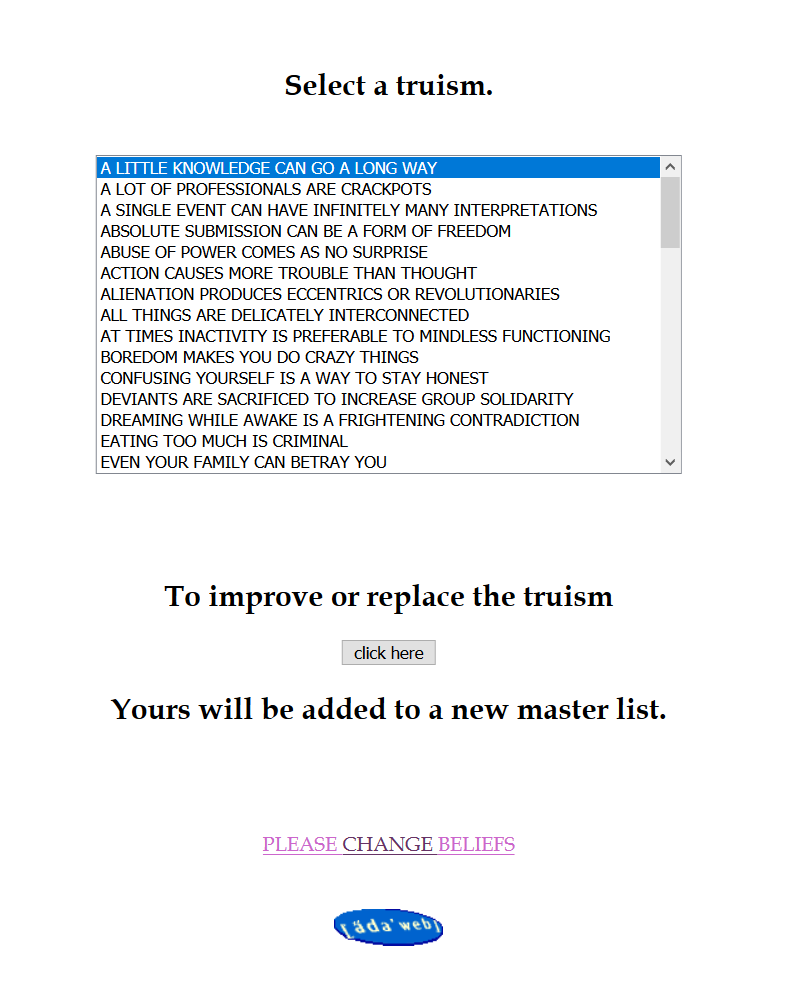

As suggested above, Maria X, who spoke on the first day, provided a clear view of key definitions. A “performance scholar”, she also spoke at length on the historical context of networked art, and how that works together with internationalism. From Paik’s Global Groove, we see a statement on his envisioned future of the “phenomenal effect” of globalised dissemination. From Satellite Arts we see the “possibilities and limitations of new technologies… to create and augment a new context and environment” (Maria X, 2018). It is interesting to see that many of these artists work in groups, since networked art necessitates interaction with other humans.

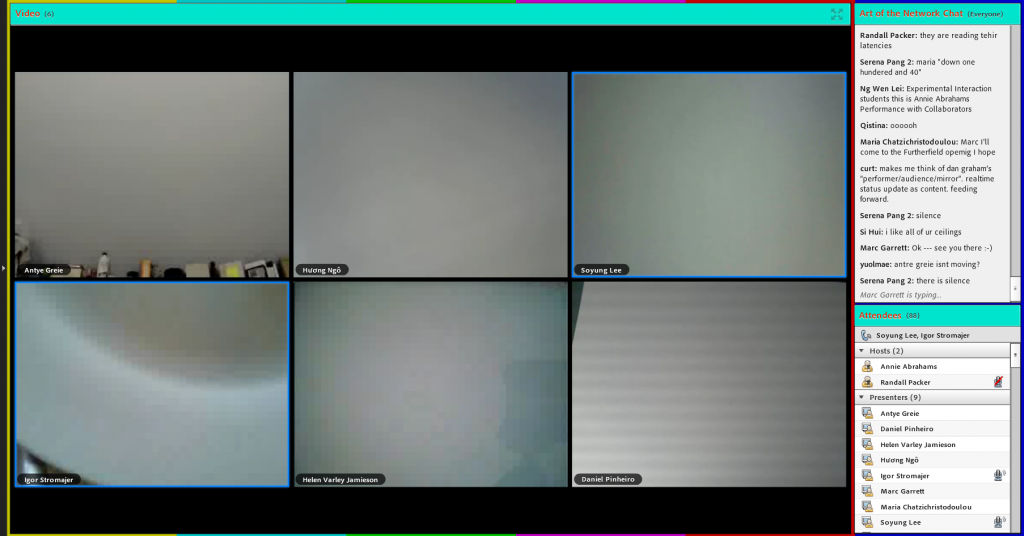

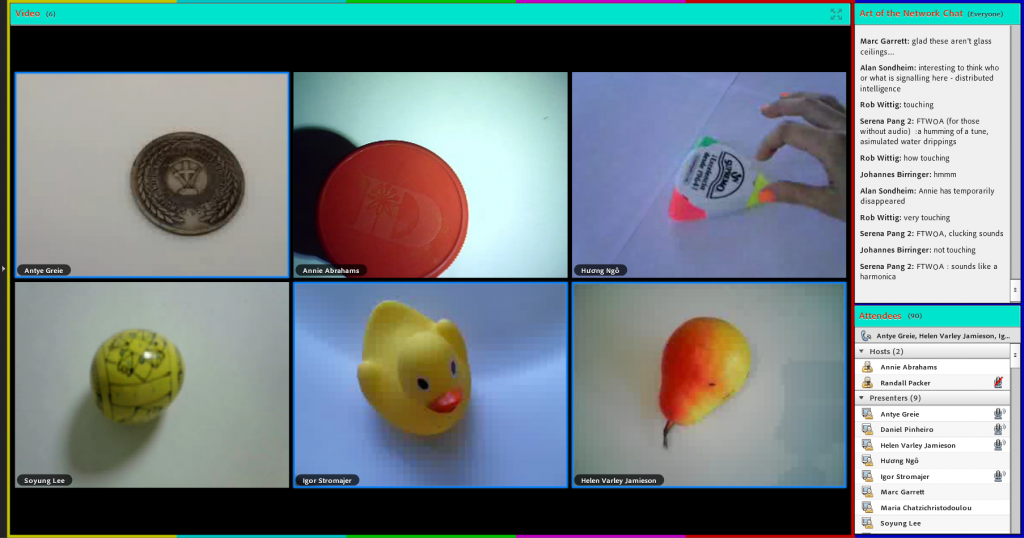

Picking up after the keynote, Annie Abrahams expanded on this idea of the need for accompaniment, with the debut of Online Ensemble – Entanglement Training. As the name suggests, the performance was an ensemble, one which can only work with a group, one supported by the natural disadvantage of being unable to synchronise digitally.

In response to a remark that it was difficult to work together, Abrahams mentioned that one can be “not in the same time and same place, but can still play together… in this entanglement of people and machines”. This is rather in line with an earlier remark that “her artworks primarily tackle “communication and the difficulty with communicating at all”.

It is evident that synchronisation is not particularly crucial since the artwork is essentially an improvised performance. The randomness of non-vetted phrases is important: phrases like “don’t ask for the truth if you can’t handle it”, “I’m sorry babe, I’m afraid I can’t do that”, “suddenly we become scared to change something” have no meaning on their own, only what we interpret on our own. As aptly put by Dixon, it is very much a fluxus work, where direction is not as important as non or omni-direction.

Dixon further elaborates on the nature of modern forms of art which come with new technologies on the second day. As previously asserted by Paik, the relationship between art and new technology is as old as art itself, from the Egyptians’ pyramids to satellite art. Relating the story of Henry Thoreau, who could not understand the purpose of the phone, Dixon explains that “although man talks to accomplish something, unawares, he soon begins to talk, simply, to talk”. It is rarely about whether there is a purpose, as to that it has come into existence, forming new relationships and new ways of thinking. Consequently, modern art emerges as a form of exploration into these “new processes in communicational processes”.

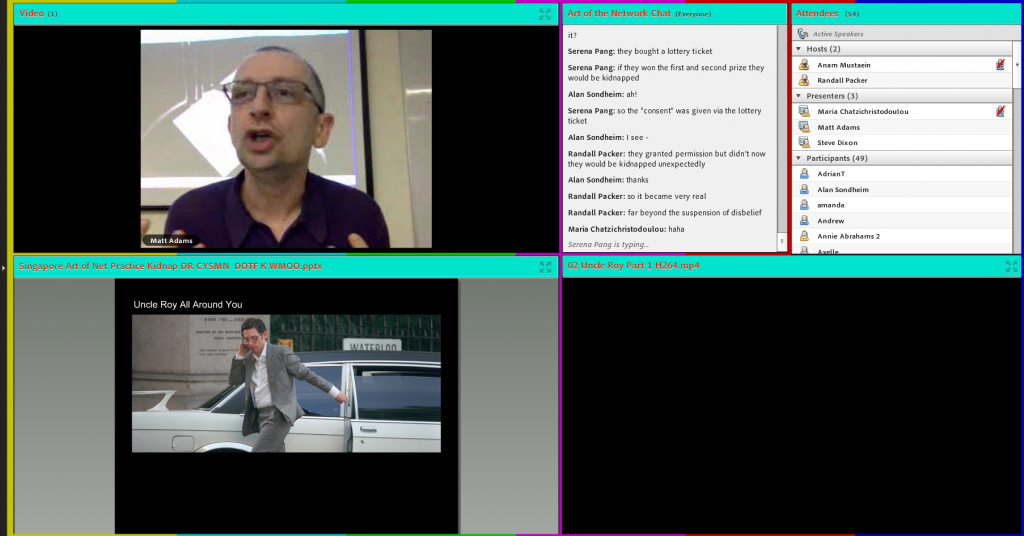

Another example he gives is that of Blast Theory, neatly tying into a quaint introduction for Matt Adams, its founder. Delving into the intricacies of simultaneously existing in reality and irreality, Blast Theory works with the idea of connecting people remotely, and the possibilities which come with that idea. It is perhaps even this which gives the theme of the day, of Networking the Real & the Fictional. In fact, it is almost a pity that Adams was not able to execute an interactive work with the audience on the spot, which may have brought the point across even more pertinently by nature of its interactivity, as opposed to speaking at length on past works and the intentions behind them.

Regardless, the various works presented are interesting, showcasing what was then a brand new style of (mostly) game-based interaction based on an augmented reality of sorts. Uncle Roy All Around You, for example, asks questions without providing a frame, making it uncertain as to if it is something out of the game or in the game. Neither can work without the other, and yet the boundaries between “reality” and this second “reality but also not really” are blurred, creating a super reality. Many games nowadays attempt, in some way or another, to replicate that crossing of reality and the digital world.

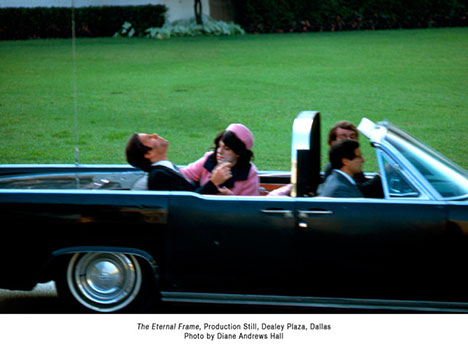

As later addressed in the Q&A, the works are also curiously tied in with the idea of control. As stated by Packer, it is often about making people acutely aware of their given or taken control, such as in Kidnap (1998). “It shapes our lives that the media has control over us,” Packer suggested, and I am not inclined to disagree. For example, as previously studied in class, we see that it is often not about acting in the capacity of a president, than acting as a president. The media has a lot of control over the narrative, and can even affect crucial national decisions.

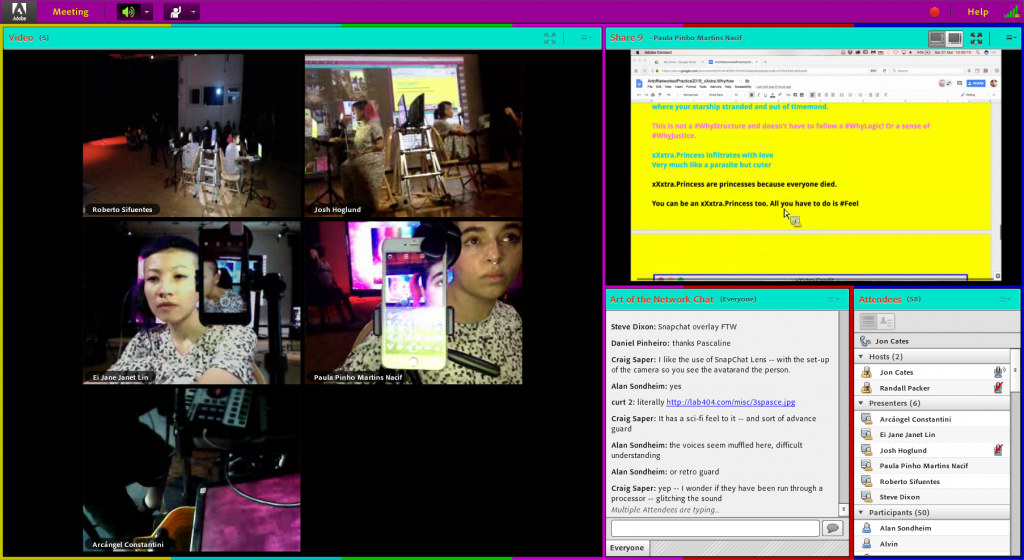

The symposium ends off with the debut of igaies (intimate glitches across internet errors), a strangely neat summary of the topics of the previous days. Personally, it is fascinating that it is pronounced as “gaze”, perhaps leaving it as a statement on its online nature (iGaies), on the connection formed by eye contact (gaze).

Jon Cates and collaborators are currently developing a series of multifarious and differentiated performance works that coalesce into what Cates refers to as igaies (intimate glitches across internet errors) – small miraculous mistakes, moments of beautiful brokenness – all fused together as a single improvisatory, real-time sensory overload of noise, blood, hashtags, fetishism, sexuality, memes, and #cutestuff. (link)

As implied by the above quote, the key idea is of glitches. Even on a more “real” perspective, though, simultaneous perspectives and/or performances hint at some sort of “glitch”, where there logically shouldn’t be an overlap to allow proper focus on the appropriate artworks. These “multifarious” artworks even appear to clash, from the girlish xxxtraprincesses to the gory leeches. Despite this, it makes a strange sort of sense. Constantini brings to the table his works on petri dishes, the image of bacteria tying in with Sifuentes’ leeches. Cates drops a beat while Constantini’s electronic sound pervades the scene. The xxxtraprincesses bring to the table a tale of revolution, all while embracing internet culture. Memes, hashtags, digital avatars all find a place here, and Nacif herself identifies as a gURL, stating that she finds this typo-ed term to “have a multiplicity and simultaneity” which gIRL does not. Sifuentes, too, brings a tale of revolution, but gorier, in the form of exsanguination, defined as “a process of mourning and cleansing with leeches being ritualistically applied to his body” on the Third Space Network.

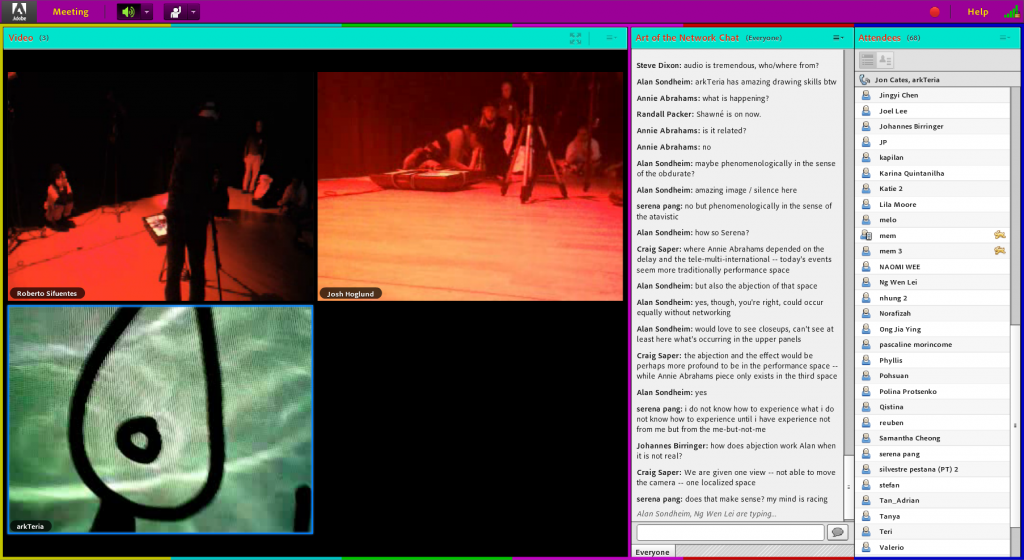

Something I was particularly struck by was the vibrancy of the chatroom, too. There could be the simplicity of one word reactions to which you’re obviously not meant to respond, to drawn out interpretations which can begin conversations on its own, to added insight on the artworks being presented. (See below for audience links which I spotted on Day 3.)

Abrahams said something to the same effect:

Sometimes I even think that the chatroom is more important than what is actually happening between the performers. Both complete each other. And I also try to have some people in the chatroom who know what it is all about, so they can mediate between people and create a live/nice atmosphere.

While I am uncertain as to if she said “nice” or “live”, I prefer to think of it as both. Niceness creates a welcoming community which connects the audience to each other; liveness brings forth the connection between the audience and the artist(s). Overall, though, it is beyond doubt that the medium truly brings out the theme: I could hardly imagine these artworks being presented traditionally. Though I believe that there are ways in which the symposium could have stretched the social broadcast medium even more to communicate even better, it is certainly remarkable, considering that the revolution has yet to be finished.

Featured image from Adams’ presentation video on Uncle Roy All Around You.

- Abrahams, A. “Souriez”. http://www.bram.org/

- Blast Theory. “Kidnap”. https://www.blasttheory.co.uk/projects/kidnap/

- Kac, E. (1998). “Satellite Art: An Interview with Nam June Paik”. On O Globo. http://ekac.org/paik.interview.html

- NASA & co. (1977). “Satellite Arts Project”. On Satellite Arts Project. http://www.ecafe.com/getty/SA/index.html

- NewHive. (2016). “Artist Paula Nacif On Inhabiting Digital Spaces”. On Paper. http://www.papermag.com/artist-paula-nacif-on-inhabiting-digital-spaces-1761889352.html

- Packer, R. (2018). “Art of the Networked Practice Online Symposium”. On the Third Space Network. https://thirdspacenetwork.com/symposium2018/

- Packer, R. (2018). “igaies – intimate glitches across internet errors”. On the Third Space Network. https://thirdspacenetwork.com/symposium2018/igaies-intimate-glitches-across-internet-errors/

- Packer, R. “Interdisciplinary Forms – Ant Farm and the Art of the Meme”. https://oss.adm.ntu.edu.sg/17s2-dn1010-tut-g05/syllabus/art-destruction/

- Packer, R. (2018). “Live Art and Telematics: The Promise of Internationalism”. On the Third Space Network. https://thirdspacenetwork.com/symposium2018/live-art-and-telematics-the-promise-of-internationalism/

- Paik, N.J. (N.A.). “Global Groove”. On Medien Kuntz Net. http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/global-grove/

- Symposium video links

- https://connect.ntu.edu.sg/p2hoimc6en3/

- https://connect.ntu.edu.sg/p64havp11a9/

- https://connect.ntu.edu.sg/p73xe8v7fkh/

- Audience links

- http://thegnuaesthetic.tumblr.com/

- https://www.cafeoto.co.uk/events/a-view-from-elsewhere/

- http://www.legacyrussell.com/GLITCHFEMINISM

- http://www.bakteria.org/