Much of social practice art critique is directed towards how it nevertheless supports capitalism, than actively helping the community. So, being curious, I looked for an example from post-war, Soviet-controlled Central Eastern Europe! (It doesn’t have anything to do with capitalism though.)

Something to take note is that the works of Krzysztof Wodiczko is often described as socially-engaged, socially-intervening and socially-minded. However, the specific term “social practice” almost never comes up, likely because it’s a relatively new term. As such, his work may not compare to things like Rick Lowes’ Project Row Houses or Marjetica Potrč’s Dry Toilet, which specifically involves designing objects for contextual use.

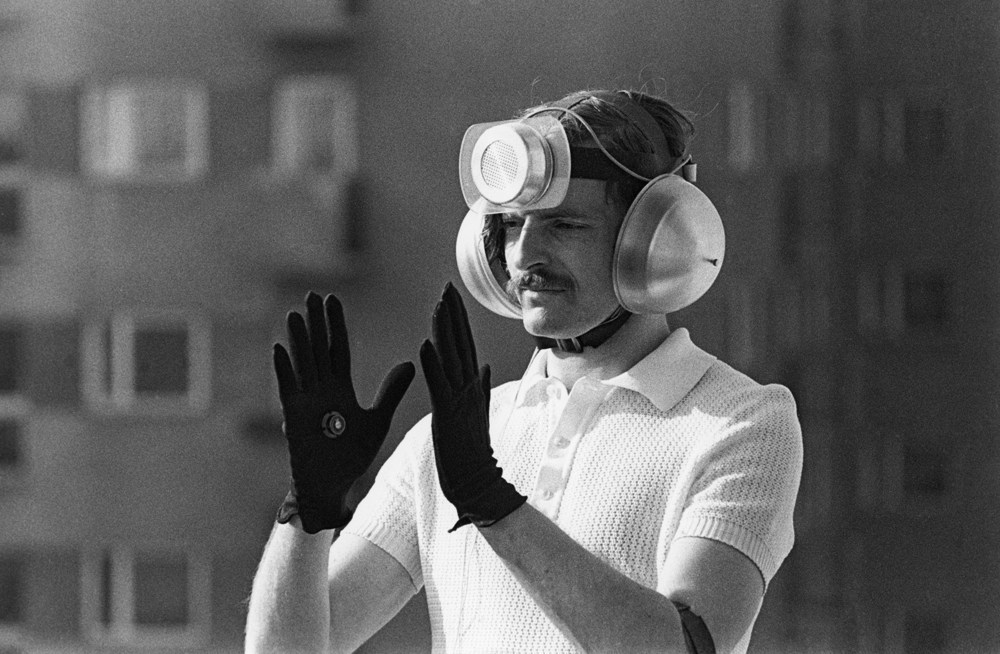

PERSONAL INSTRUMENT (1969)

This artwork is one of the first interactive wearables to target the issue of freedom in an oppressive state. At that time, the artist, Krzysztof Wodiczko, was inspired by Vladmir Mayakovsky‘s claim that “the streets [are] our brushes, the squares our palettes”. In other words, art relies on the surroundings, and is not a purely isolated piece. At that time, too, Poland was under an authoritarian communist regime, wracked by lack of freedom, poverty and poor living conditions. Harsh treatment, detention and executions were hardly uncommon: One could not speak out against the government for fear of terrible repercussions. At best, they could submerge their hidden messages within a veil of unmeaningful speech.

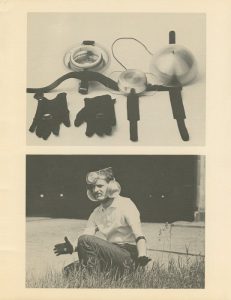

(Images as found at https://artmuseum.pl/en/performans/archiwum/2519/127280.)

Consequently, the interactive wearable aimed to present a state of “listening selectively” while remaining voiceless, where the only available freedom was what one chose to filter in or out. Equipped with photoreceivers and a microphone, the wearable was thus capable of modifying the received sounds, in relation to hand gestures by the wearer. As stated by the artist himself, too, it was designed as an “appliance” with “expressly defined function”, in such a way that it could act as a potential solution to the social problem of political voicelessness.

ITS RELATION TO SOCIAL PRACTICE ART

Where the intention involves the betterment of society in the face of a social and political issue, Personal Instrument has the makings of social practice art. Despite that, there are many ways in which it does not qualify.

For one, it was built for “the exclusive use of the artist who created it”. Though Wodiczko said, in hindsight, that “the whole Polish society should have been equipped with a device of this kind”, it simply never happened. This has the impact of that it honestly didn’t help society at all. For two, it still tends towards representing the issue, than solving it. I highly doubt that being able to modify surrounding sounds with your hands has much implication on improving the problem of political freedom. Again, little impact on improving society.

There are hints of that it is simply an unrefined first foray, especially when compared to later works (like above). Nevertheless, I don’t think that it is simply a problem of poor design conception. This is because there were severe design limitations. For example, that he built this anti-state piece during his tenure at a state-operated organisation. Or, that he was exiled from Poland soon after by the government, without any justification given. Simply put, it’s hardly ideal to be advertising anti-government art in a context of large governmental control. While many of his later works have multiple iterations to improve the design, too, Personal Instrument likely couldn’t get that same treatment due to 1) the sensitivity of the content for the government, and 2) that Poland is no longer under an authoritarian regime anyway.

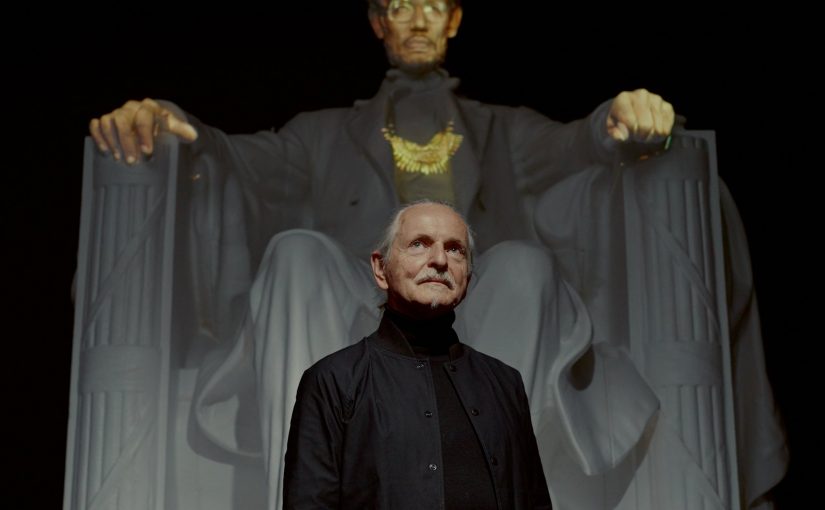

From this, perhaps it could be said that a supportive environment is ironically needed as well. Not only must there be an existing social problem, the society must be able to accept critical views of that problem. Some of his later works, for example, had a greater impact in terms of visibility, where it could be openly paraded around to make rich people uncomfortable:

As mentioned above, Wodiczko’s works are still “not about solving individual problems, but about bringing out, exposing, manifesting the social needs which they respond to” (Musielak, 2015). Instead, he subscribes to is something known as Interrogative Design, or Scandalising Functionalism. These terms refer to a form of functional design which is scandalous by its very existence, because the problem it’s addressing should never have existed at all. While this contradicts the requirement of social practice art to solve the problem than show it, it does raise a pertinent issue: that any artistic solution still wouldn’t be able to solve the key cause of the problem. As shown in the previous article, for example, Project Row Houses is an ideal which can’t accommodate the true scale of the housing issue. Similarly, building more Homeless Vehicles doesn’t change the fact that the system itself is generating homelessness.

In which case, perhaps social practice art doesn’t need to answer a problem. Instead, it might merely need to provoke revolution, in rousing sufficient feelings to bring about change which stops the problem at its source.

REFERENCES

- Davis, B. (2013). A Critique of Social Practice Art. In International Socialist Review, Issue #90. As found at https://isreview.org/issue/90/critique-social-practice-art

- Galliera, I. (2017). Socially Engaged Art After Socialism: Art and Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe (Book Review). As found at https://artmargins.com/shaping-democratic-notions/

- Krzysztof Wodiczko. For Culture.pl. As found at https://culture.pl/en/artist/krzysztof-wodiczko

- Krzysztof Wodiczko – Personal Instrument (1969). For Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej. As found at https://artmuseum.pl/en/performans/archiwum/2519?read=all

- Sheets, H. M. (2020). A Monument Man Gives Memorials New Stories to Tell. For The New York Times. As found at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/arts/design/Krzysztof-Wodiczko.html

- Featured Image