Sach Plakat / Plakatstil

Lucian Bernhard, Manoli Cigarettes, 1910.

Lucian Bernhard, Manoli Cigarettes, 1910.

Sach Plakat or Plakatstil, which literally meant “object-poster” and “poster style” in German respectively, was a style developed in 1905 by Lucian Bernhard in Berlin. During the start of the twentieth century in Germany, the complex and decorative forms of Art Nouveau were replaced with emphasis on strong vibrant colours, abstract and simplified flat shapes, typography / message which was reduced to the bare minimum, and a rejection of anything decorative. Designers and artists wanted their works to be more easily read and understood by the passerbys.

Lucian Berhard

Lucian Bernhard, Priester, 1906.

Lucian Bernhard, Priester, 1906.

It was started by Lucian Bernhard when he took part in a poster competition held by Preister Matches, and he took a creative approach of drawing two large matches, and wrote the brand name above them in bold letters. The stark simplicity and cleanness enabled him to win the competition, and it marked the departure from the complexity of the Art Nouveau style in Germany. His reductive and flat imagery subsequently became the foundation for a revolution in commercial advertising in pre-war Berlin, and was spread throughout Europe and the United States.

Ludwig Hohlwein

Ludwig Hohlwein, Direct China Cotton Importers – Wonalancet, 1909.

Ludwig Hohlwein, Direct China Cotton Importers – Wonalancet, 1909.

Ludwig Hohlwein, Vivator, 1912.

Ludwig Hohlwein, Vivator, 1912.

Other notable works done in the Sach Plakat style was that of Ludwig Hohlwein’s. His poster designs were primarily influenced by the collage technique of the British poster designers The Beggarstaffs, and he took inspiration from the emphasis on simplicity, pattern, silhouette, integral typography, and the usage of a limited colour palette.

Oto Baumberger

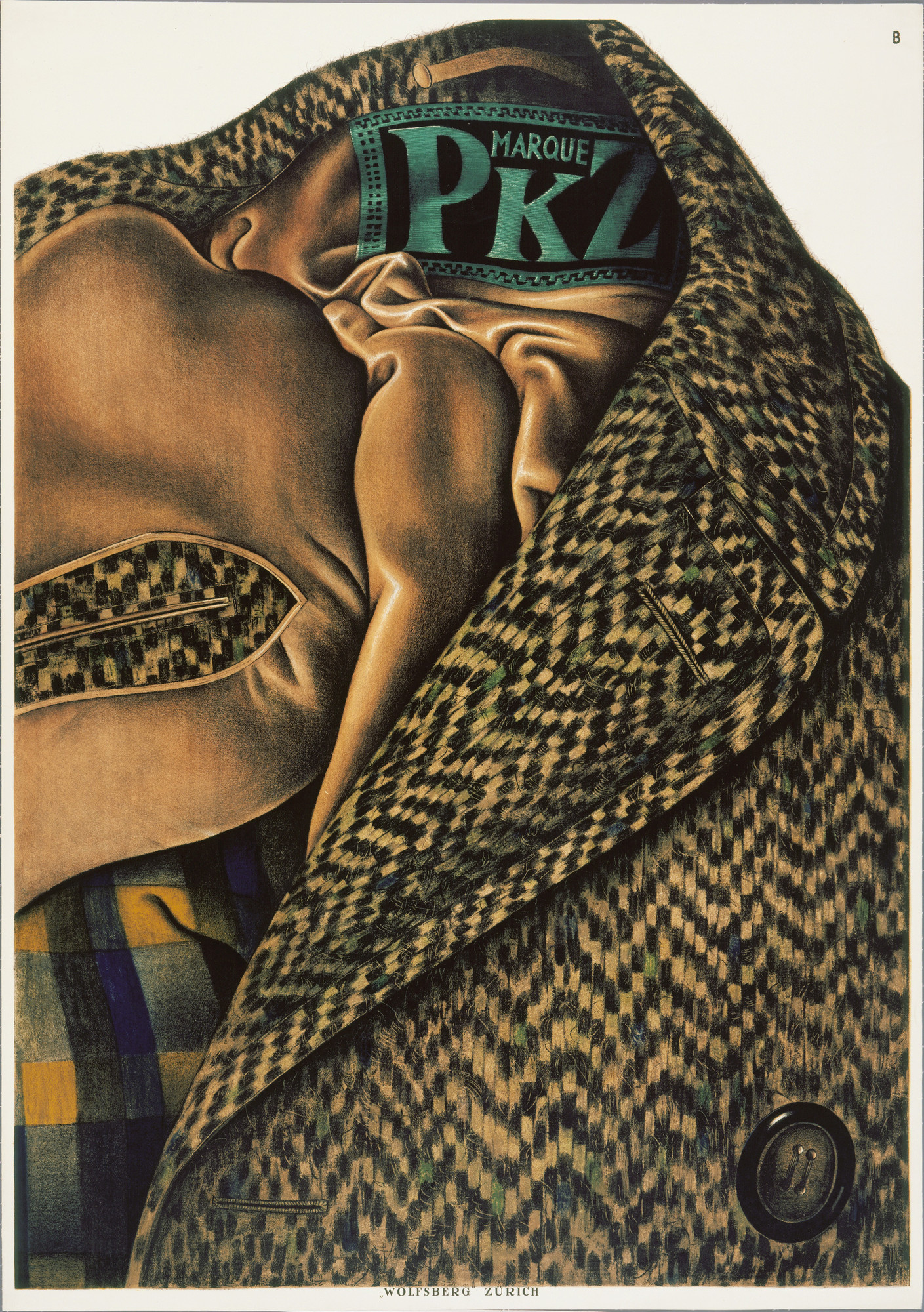

Otto Baumberger, Marque PKZ, 1923.

Otto Baumberger, Marque PKZ, 1923.

Over time, the flat style that was developed by Lucian Bernhard was expanded into a more colourful and realistic style, but the emphasis on just the product and the brand name or minimum text was still there. In 1923, Swiss designer Otto Baumberger drew a tweed coat for PKZ with its label serving as the only text in the poster. Many people mistook the poster for a photograph.

The style was prominent until the Great War in Europe. After the war, advertising techniques re-shifted once again, and the Sach Plakat style declined. However, this revolutionary modern outlook on poster design and advertising in the early twentieth century no doubt still have an impact in the design industry today, as the style or its influence can still be seen in many designs in present day.

https://www.moma.org/artists/2700

http://www.iconofgraphics.com/Ludwig-Hohlwein/

https://www.internationalposter.com/style-primers/plakatstil-the-poster-style/