I also made a comprehensive post on my other webpage for everything I’ve presented so far <:

abstract

The work aims to explore the concept of monstrosity in a world of mundanity, creating a hyperbolic dystopia that brings to light the horrors of the everyday. Drawing from the sensational Sada Abe Incident that spurred the ero-guro-nansensu movement in 1930s Japan, the work is a experimental illustrated narrative that reinterprets hellish landscapes, situations and characters.

Looking to themes of horror, macabre, monstrosity, the abhuman and studies in abjection, I look to explore surrealist and absurdist illustration while experimenting with the creation and curation of narratives in different forms, informing the experience.

case study

drawing from the works of junji ito, hieronymous bosch, edogawa rampo and makoto aida, the narrative is one that combines the visual aspects of horror and the unknown with familiar themes within acceptable society.

some background

The Sada Abe incident

The Sada Abe incident in 1936 was a highlight of the Ero guro Movement. Sada Abe, a former prostitute, killed her lover by choking him in and after coitus, then severing his genitalia and fleeing. When captured, she was pictured smiling with the officer, who did not believe her until she showed him her lovers genitalia as proof.

She said, “After I had killed Ishida I felt totally at ease, as though a heavy burden had been lifted from my shoulders, and I felt a sense of clarity.” and that “(she) loved him so much, (she) wanted him all to (her)self.” Mark Schreiber argues that the national sensation this scandal produced was a welcome distraction for a Japan facing political and military tumult.

(Schreiber, Mark (2001). “O-sada Serves a Grateful Nation”. the dark side: infamous japanese crimes and criminals. tokyo: kodansha. pp. 184–190. isbn 978-4-7700-2806-8.)

the abhuman

Abhuman is a term used to distinguish a separation from normal human existence.

In literary studies of Gothic fiction, abhuman refers to a “Gothic body” or something that is only vestigially human and possibly in the process of becoming something monstrous. Kelly Hurley writes that the “abhuman subject is a not-quite-human subject, characterized by its morphic variability, continually in danger of becoming not-itself, becoming other.”

Allan Lloyd Smith writes that among “the sources of abhuman Gothic horror for many writers at this time were the urban squalor and misery of overcrowded cities.

Jerrold E. Hogle, The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction page 190 (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Kelly Hurley, The Gothic Body: Sexuality, Materialism, and Degeneration at the Fin de Siècle (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 3. This quotation also appears in Robert Eaglestone, Reading The Lord of the Rings: New Writings on Tolkien’s Classic page 55 (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006).

Allan Lloyd Smith, American Gothic Fiction: An Introduction page 114 (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004).

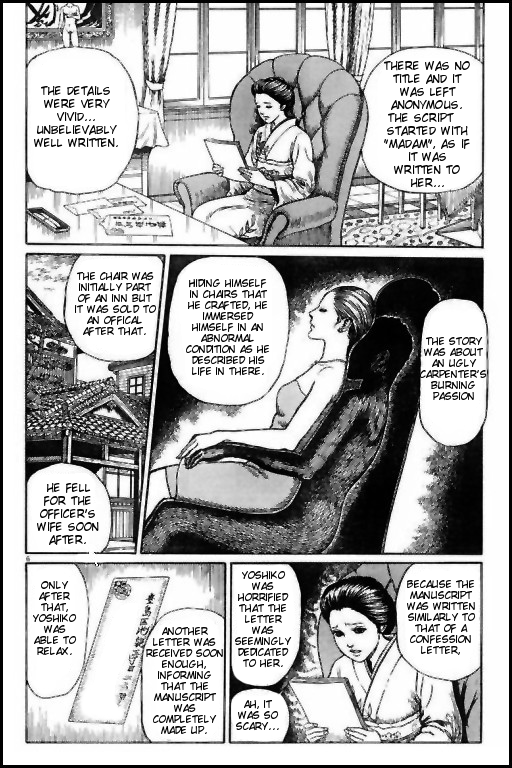

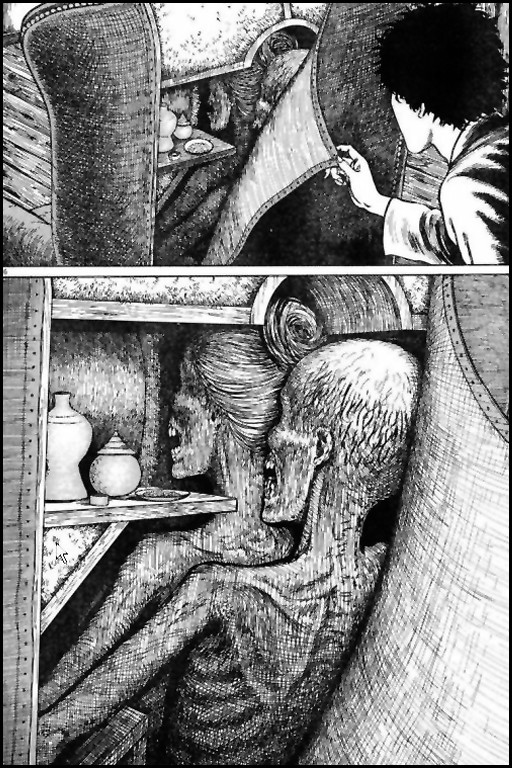

case studies: edogawa rampo

Otherwise known as Tarō Hirai, Rampo was the president of the Japanese Association of Mystery writers, and a pioneer of Japanese Mystery Fiction. Works of his include Caterpillar and The Human Chair. The work, The Human Chair, was drawn into the form of manga by Junji Ito, after his death. Rampo’s work took on a more hedonistic turn around the 1930s, influenced by the turbulent ero-guro-nansensu movement, and the influx of Western ideas.

Junji ito

Junji Ito is a horror manga writer, inker, penciller and comic artist known for the capricious and cruel world he sets his stories in. His characters are often victims of unexplained and unnatural encounters that are relatable in a modern environment

Excerpt from Junji Ito’s Uzumaki, where a small town erupts in hysteria over spirals.

In my pursuit of a narrative that involved a little more photomanipulation, I looked up Dave McKean’s work in the Sandman series by Neil Gaiman, and in Signal to Noise, a story of a personal apocalypse of a dying filmmaker amidst an imagined World Apocalypse. I also found a excerpt from Arkham Asylum that I liked.

Seeing the works inspired me to produce, and spurred me to push further toward the absurdities of Boschian hell (by the way, someone has transcribed the music that Bosch depicted on a poor mortals bottom)

Poor Mortal crushed by a harp with sheet music on their posterior, The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymous Bosch, 1503-04

Poor Mortal crushed by a harp with sheet music on their posterior, The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymous Bosch, 1503-04

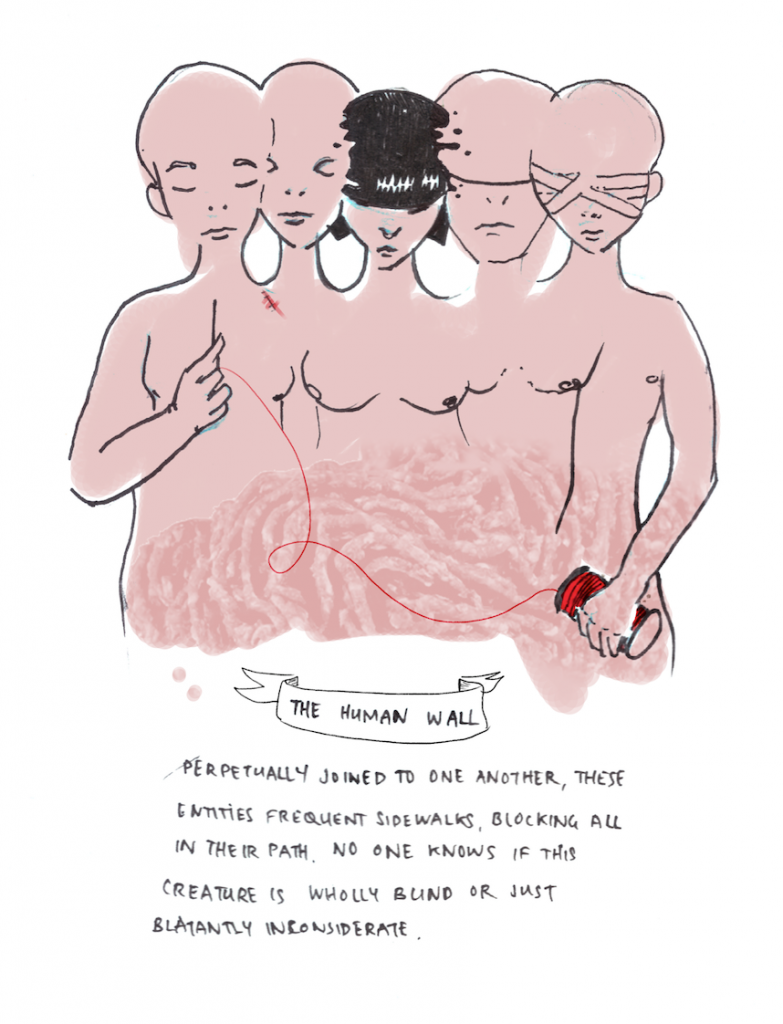

I produced work based on the terrible phenomena of people blocking my way by forming crowds at busstops and crowding pavements, just to have a conversation,

I then arranged everything on an acrylic board to get an idea of the flow of the narrative.

I also did a variety of other drawings centered around this style, and eventually morphed into something more graphic and stylised.

produced this, as a sample for the media wall.

as well as something that would hopefully merge both styles.

daphne of greek myth (i was inspired by the possibility of integrating myth. (i.e dante’s inferno). started to looked very Mucha.

Going with the encouragement to pursue photomontage as well as illustration, I sought out the work of Yobunoshi Araki, to find pictures of the disturbing and abject, a term described by Julia Kristeva as “the human reaction (horror, vomit) to a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other. The primary example for what causes such a reaction is the corpse (which traumatically reminds us of our own materiality); however, other items can elicit the same reaction: the open wound, shit, sewage, even the skin that forms on the surface of warm milk.” I found Araki’s work to be an extension of this.

The format has also inspired me towards a zine or publication, the red amplifies the effect the seemingly graphic and disturbing images have on the viewer, though seen without a context and with a mind devoid of suggestion, the images may look mundane, even. A common theme is hair, orifices and organic clusters of matter, that might spur on tryphophobia (fear of holes) which i might employ in my work. This is also seen in Alessandro Bavari’s work.

“Alessandro the child artist would sit at a table drawing pictures of clowns with bare breasts and the Madonna with a moustache. In time, these childlike and whimsical representations morphed into darker, distorted, more unsettling interpretations of the human psyche. The work of Alessandro the adult artist, a fusion of mixed-media techniques, inspired by childhood impressions, delves into the very bowels of human despair.”

Lady Lazarus by Sylvia Plath

I have done it again.

One year in every ten

I manage it—–

A sort of walking miracle, my skin

Bright as a Nazi lampshade,

My right foot

A paperweight,

My featureless, fine

Jew linen.

Peel off the napkin

O my enemy.

Do I terrify?——-

The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth?

The sour breath

Will vanish in a day.

Soon, soon the flesh

The grave cave ate will be

At home on me

And I a smiling woman.

I am only thirty.

And like the cat I have nine times to die.

This is Number Three.

What a trash

To annihilate each decade.

What a million filaments.

The Peanut-crunching crowd

Shoves in to see

Them unwrap me hand and foot ——

The big strip tease.

Gentleman , ladies

These are my hands

My knees.

I may be skin and bone,

Nevertheless, I am the same, identical woman.

The first time it happened I was ten.

It was an accident.

The second time I meant

To last it out and not come back at all.

I rocked shut

As a seashell.

They had to call and call

And pick the worms off me like sticky pearls.

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

I do it so it feels like hell.

I do it so it feels real.

I guess you could say I’ve a call.

It’s easy enough to do it in a cell.

It’s easy enough to do it and stay put.

It’s the theatrical

Comeback in broad day

To the same place, the same face, the same brute

Amused shout:

‘A miracle!’

That knocks me out.

There is a charge

For the eyeing my scars, there is a charge

For the hearing of my heart—

It really goes.

And there is a charge, a very large charge

For a word or a touch

Or a bit of blood

Or a piece of my hair on my clothes.

So, so, Herr Doktor.

So, Herr Enemy.

I am your opus,

I am your valuable,

The pure gold baby

That melts to a shriek.

I turn and burn.

Do not think I underestimate your great concern

Ash, ash—

You poke and stir.

Flesh, bone, there is nothing there—-

A cake of soap,

A wedding ring,

A gold filling.

Herr God, Herr Lucifer

Beware

Beware.

Out of the ash

I rise with my red hair

And I eat men like air.

An analysis of Lady Lazarus by Jon Rosenblatt from Sylvia Plath: The Poetry of Initiation. Copyright © 1979 by University of North Carolina Press.

“. . . The poem reflects Plath’s recognition at the end of her life that the struggle between self and others and between death and birth must govern every aspect of the poetic structure. The magical and demonic aspects of the world appear in “Lady Lazarus” with an intensity that is absent from “The Stones.”

The Lady of the poem is a quasi-mythological figure, a parodic version of the biblical Lazarus whom Christ raised from the dead. As in “The Stones,” the speaker undergoes a series of transformations that are registered through image sequences. The result is the total alteration of the physical body. In “Lady Lazarus,” however, the transformations are more violent and more various than in “The Stones,” and the degree of self-dramatization on the part of the speaker is much greater. Four basic sequences of images define the Lady’s identity. At the beginning of the poem, she is cloth or material: lampshade, linen, napkin; in the middle, she is only body: knees, skin and bone, hair; toward the end, she becomes a physical object: gold, ash, a cake of soap; finally, she is resurrected as a red-haired demon. Each of these states is dramatically connected to an observer or observers through direct address: first, to her unnamed “enemy”; then, to the “gentlemen and ladies”; next, to the Herr Doktor; and, finally, to Herr God and Herr Lucifer. The address to these “audiences” allows Plath to characterize Lady Lazarus’s fragmented identities with great precision. For example, a passage toward the end of the poem incorporates the transition from a sequence of body images (scars-heart-hair) to a series of physical images” (opus-valuable-gold baby) as it shifts its address from the voyeuristic crowd to the Nazi Doktor:

[lines 61-70]

The inventiveness of the language demonstrates Plath’s ability to create, as she could not in “The Stones,” an appropriate oral medium for the distorted mental states of the speaker. The sexual pun on “charge” in the first line above; the bastardization of German (“Herr Enemy”); the combination of Latinate diction (“opus,” “valuable”) and colloquial phrasing (“charge,” “So, so . . . “)—all these linguistic elements reveal a character who has been grotesquely split into warring selves. Lady Lazarus is a different person for each of her audiences, and yet none of her identities is bearable for her. For the Nazi Doktor, she is a Jew, whose body must be burned; for the “peanut-crunching crowd,” she is a stripteaser; for the medical audience, she is a wonder, whose scars and heartbeat are astonishing; for the religious audience, she is a miraculous figure, whose hair and clothes are as valuable as saints’ relics. And when she turns to her audience in the middle of the poem to describe her career in suicide, she becomes a self-conscious performer. Each of her deaths, she says, is done “exceptionally well. / I do it so it feels like hell.”

The entire symbolic procedure of death and rebirth in “Lady Lazarus” has been deliberately chosen by the speaker. She enacts her death repeatedly in order to cleanse herse1f of the “million filaments” of guilt and anguish that torment her. After she has returned to the womblike state of being trapped in her cave, like the biblical Lazarus, or of being rocked “shut as a seashell,” she expects to emerge reborn in a new form. These attempts at rebirth are unsuccessful until the end of the poem. Only when the Lady undergoes total immolation of self and body does she truly emerge in a demonic form. The doctor burns her down to ash, and then she achieves her rebirth:

Out of the ash

I rise with my red hair

And I eat men like air.

Using the phoenix myth of resurrection as a basis, Plath imagines a woman who has become pure spirit rising against the imprisoning others around her: gods, doctor, men, and Nazis. This translation of the self into spirit, after an ordeal of mutilation, torture, and immolation, stamps the poem as the dramatization of the basic initiatory process.

“Lady Lazarus” defines the central aesthetic principles of Plath’s late poetry. First, the poem derives its dominant effects from the colloquial language. From the conversational opening (“I have done it again”) to the clipped warnings of the ending (“Beware / Beware”), “Lady Lazarus” appears as the monologue of a woman speaking spontaneously out of her pain and psychic disintegration. The Latinate terms (“annihilate,” “filaments,” “opus,” “valuable”) are introduced as sudden contrasts to the essentially simple language of the speaker. The obsessive repetition of key words and phrases gives enormous power to the plain style used throughout. As she speaks, Lady Lazarus seems to gather up her energies for an assault on her enemies, and the staccato repetitions of phrases build up the intensity of feelings:

[lines 46-50]

This is language poured out of some burning inner fire, though it retains the rhythmical precision that we expect from a much less intensely felt expression. It is also a language made up almost entirely of monosyllables. Plath has managed to adapt a heightened conversational stance and a colloquial idiom to the dramatic monologue form.

The colloquial language of the poem relates to its second major aspect: its aural quality. “Lady Lazarus” is meant to be read aloud. To heighten the aural effect, the speaker’s, voice modulates across varying levels of rhetorical intensity. At one moment she reports on her suicide attempt with no observable emotion:

I am only thirty.

And like the cat I have nine times to die.

This is Number Three.

The next moment she becomes a barker at a striptease show:

Gentlemen, ladies,

These are my hands.

Then she may break into a kind of incantatory chant that sweeps reality in front of it, as at the very end of the poem. The deliberate rhetoric of the poem marks it as a set-piece, a dramatic tour de force, that must be heard to be truly appreciated. Certainly it answers Plath’s desire to create an aural medium for her poetry.

Third, “Lady Lazarus” transforms a traditional stanzaic pattern to obtain its rhetorical and aural effects. One of the striking aspects of Plath’s late poetry is its simultaneous dependence on and abandonment of traditional forms. The three-line stanza of “Lady Lazarus” and such poems as “Ariel,” “Fever 103°,” “Mary’s Song,” and “Nick and the Candlestick” refer us inevitably to the terza rima of the Italian tradition and to the terza rima experiments of Plath’s earlier work. But the poems employ this stanza only as a general framework for a variable-beat line and variable rhyming patterns. The first stanza of the poem has two beats in its first line, three in its second, and two in its third; but the second has a five-three-two pattern. The iambic measure is dominant throughout, though Plath often overloads a line with stressed syllables or reduces a line to a single stress. The rhymes are mainly off-rhymes (“again,” “ten”; “fine,” “linen”; “stir,” “there”). Many of the pure rhymes are used to accentuate a bizarre conjunction of meaning, as in the lines addressed to the doctor: “I turn and burn. / Do not think I underestimate your great concern.”

Finally, “Lady Lazarus,” like “Daddy” and “Fever 103°,” incorporates historical material into the initiatory and imagistic patterns. This element of Plath’s method has generated much misunderstanding, including the charge that her use of references to Nazism and to Jewishness is inauthentic. Yet these allusions to historical events form part of the speaker’s fragmented identity and allow Plath to portray a kind of eternal victim. The very title of the poem lays the groundwork for a semicomic historical and cultural allusiveness. The Lady is a legendary figure, a sufferer, who has endured almost every variety of torture. Plath can thus include among Lady Lazarus’s characteristics the greatest contemporary examples of brutality and persecution: the sadistic medical experiments on the Jew’s by Nazi doctors and the Nazis’ use of their victims’ bodies in the production of lampshades and other objects. These allusions, however, are no more meant to establish a realistic historic norm in the poem than the allusions to the striptease are intended to establish a realistic social context. The references in the poem—biblical, historical, political, personal—draw the reader into the center of a personality and its characteristic mental processes. The reality of the poem lies in the convulsions of the narrating consciousness. The drama of external persecution, self-destructiveness, and renewal, with both its horror and its grotesque comedy, is played out through social and historical contexts that symbolize the inner struggle of Lady Lazarus.

The claim that Plath misuses a particular historical experience is thus incorrect. She shows how a contemporary consciousness is obsessed with historical and personal demons and how that consciousness deals with these figures. The demonic characters of the Nazi Doktor and of the risen Lady Lazarus are surely more central to the poem’s tone and intent than is the historicity of these figures. By imagining the initiatory drama against the backdrop of Nazism, Plath is universalizing a personal conflict that is treated more narrowly in such poems as “The Bee-Meeting” and “Berck-Plage.” The fact that Plath herself was not Jewish has no bearing on the legitimacy of her employment of the Jewish persona: the holocaust serves her as a metaphor for the death-and-life battle between the self and a deadly enemy. Whether Plath embodies the enemy as a personal friend, a demonic entity, a historical figure, or a cosmic force, she consistently sees warfare in the structural terms of the initiatory scenario. “Lady Lazarus” is simply the most powerful and successful of the dramas in which that enemy appears as the sadistic masculine force of Nazism.”

A reflection

I read this poem and felt it echoed the fragmentation and the turmoil of a soul in multiple “rebirths”, and societal despair, the tone of some parts of the poem reminiscent of a caller advertising a circus show or a cabaret/freak show theme. The detachment of the body “Gentlemen, ladies/These are my hands” and the metaphor of dismemberment of the body in the listing of individual parts “My right foot/A paperweight”, “The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth?”. I could analyse this further? I found it fit in the fragmentation I was meaning to convey, not directly perhaps, but it gives me a strange sense of how I might like to approach this. An experimental narrative, or a self written story, of the rising, of the risen body, of an ill body, and perhaps the liminal body, which conveys a transience, in an abhuman form.

Alright, not really. Zelda’s not present. I just made this post (first post of many like these) to feature some of the articles I have been reading to bring me closer to a concrete idea. That is, if I can stop myself from stirring the concrete before it sets. Might not be a terrible thing however — like most things, this little thing is transient.

Article/blogpost by Jennifer Linton with an alternative, societal definition of ero guro nansensu, taken in the context of counterculture rebellion.

This post will focus on exploring the narratives that could be illustrated, and exploring the “abhuman”

The Abhuman

In literary studies of Gothic fiction, abhuman refers to a “Gothic body” or something that is only vestigially human and possibly in the process of becoming something monstrous,[4] such as a vampire[5] or werewolf.[6] Kelly Hurley writes that the “abhuman subject is a not-quite-human subject, characterized by its morphic variability, continually in danger of becoming not-itself, becoming other.”[7]

In the same way this leads me some possible purposes of this (probable) zine based exploration, and some questions to ponder, possibly explored within an experimental narrative: