HISTORICISM & INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The Industrial Revolution is a term popularised by English economic historian Arnold Toynbee, to describe Britain’s economic development from 1760 to 1840 (Britannica, 2018). The revolution began in Britain in late 17th century, known as a period of transition from an economy that consumed handicraft and agrarian goods, to one that thrived on mass manufacturing in a machine-driven industry. With a politically stable society and being the world’s leading colonial power at the time, the demand for British goods increased as Britain’s colonies could serve as a source for raw materials and a marketplace for manufactured goods. As such, more cost-effective methods of production were needed, therefore leading to the rise of mechanisation and the factory system (“Industrial Revolution”, 2009).

The Industrial Revolution was split into two periods, the first being largely bound to Britain from the 1760s to 1830s. To remain ahead in the economy, the British disallowed exportation of machinery, skilled workers and manufacturing techniques abroad. However, with potential profitable industrial opportunities abroad, knowledge eventually spread to other parts of the world, where Belgium then became the first country in Europe to pick up the revolution, with developed machine stops in Liège. The “new” Industrial Revolution then took place during the late 19th and 20th centuries where previously centred in iron, coal and textiles, the industry began to utilise natural and synthetic resources such as lighter metals, new alloys, plastics and new energy sources. Developments were also made to machines, tools and computers that led to the rise of automatic factories that heavily impacted the manufacturing industry in the second half of the 20th century.

Key Features

The expansion of technology and invention of new machines during the revolution brought great transformation to the textile and steam engine industries. Prior to the revolution, textiles such as wool and cotton were hand-spun and produced inefficiently in local homes (“The Spinning Jenny: A Woolen Revolution”). Various inventions through the revolution had allowed the industry to advance in terms of efficiency, quality and cost. The most prominent invention credited to have moved the textile industry from homes to factories is known to be the Spinning Jenny, invented around 1764 by Englishman James Hargreaves. It was the first hand-powered machine to enable individuals the ability to produce eight threads simultaneously instead of one, thus reducing production time. By Hargreaves’ death in 1778, there were over 20,000 spinning jennys being used across Britain (“Industrial Revolution”, 2009). Other significant inventions include the Water Frame by Richard Arkwright in 1769, which was the first textile machine to be automatically powered by water (Bellis). This invention enabled the shift from local home manufacturing to factory production of textiles due to the large size of the machines and need for large water bodies for power. Samuel Compton also invented the Spinning Mule in 1779, which formed a hybrid of the moving carriage of the Spinning Jenny and the rollers of the Water Frame. The Spinning Mule allowed for large-scale manufacturing of high quality thread that worthed a better price in the market, paving the way from an agrarian society to an industrial economy (Bellis).

Steam power was also another key aspect of the Industrial Revolution. In 1712, Englishman Thomas Newcomen invented the Atmospheric Steam Engine, which was the first mechanical engine to pump water through the use of condensed steam (“Newcomen’s steam revolution”). This invention became an important method that allowed mines to be emptied further without having to employ large number of horses to do the pumping. By 1778, James Watt then further improved this invention in terms of fuel efficiency by adding a separate condenser and cylinder seals (“Industrial Revolution”, 2009). As such, the Industrial Revolution observed significant technological advancements that undoubtedly heavily impacted Britain, and eventually the world’s economy and society.

Influences and Impacts

The Industrial Revolution observed significant technological, social and economic impacts. Seen through the advancements in the textile and steam engine industries, the Industrial Revolution saw an abundance of technological improvements. This includes the shift in the types of materials used for manufacture, such as from wood, bricks and stone to exploiting materials such as iron and steel, as well as generating energy from an abundance of coal in place of burning depleting supplies of wood and water wheels. Telegraphs also allowed for almost instantaneous communication across the country and subsequently all over the world, while the invention of steam engines also led to locomotives, improving travel efficiency (Britannica, 2018). These technological changes therefore allowed for efficiency in use of natural resources as well as in mass production of goods.

While the Industrial Revolution brought about a greater volume and variety of goods, raising the standards of living for the middle and upper classes, there was a heavy drop for those of the working class. This includes having low wages for factory labourers while working conditions were dangerous and monotonous, as well as an instability of job security for both unskilled and skilled craftspeople who could easily be replaced by machines. Child labour also saw many younger than 15 working long hours for hazardous tasks, such as cleaning of machines. In the later part of the 19th century, the British government started various labour reforms which helped to improve conditions for the working class as they gained rights to form trade unions (“Industrial Revolution”, 2009).

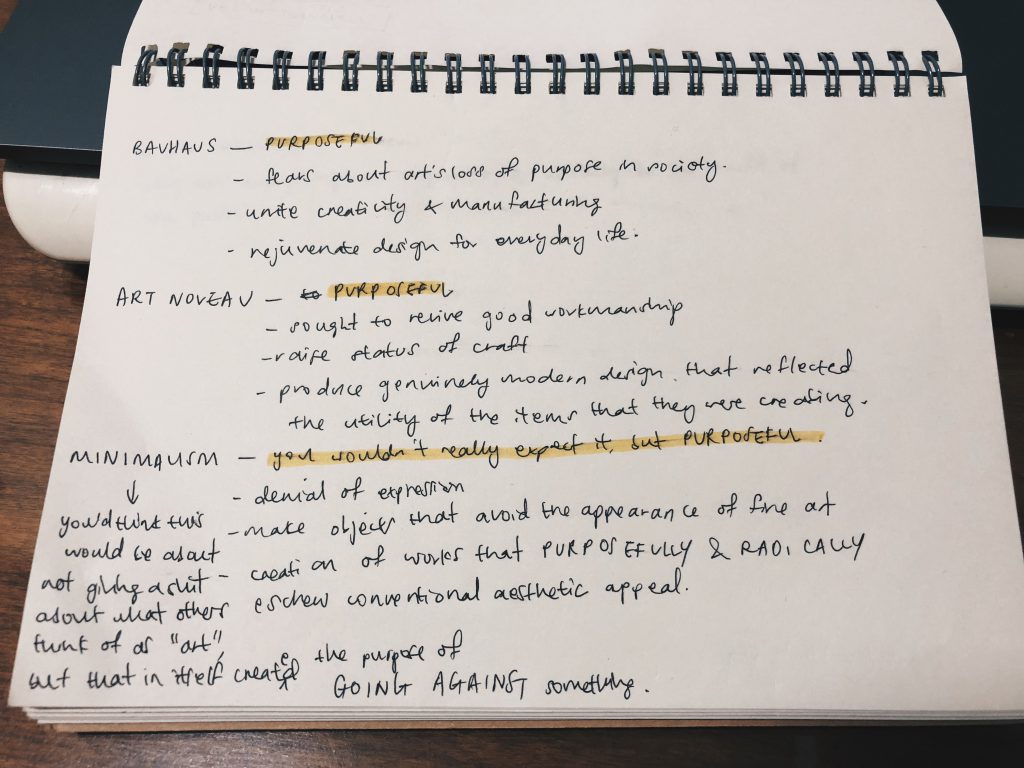

However, despite the problematic social downfall, the Industrial Revolution promoted the idea of globalisation and pushed for better designs with new technology, where the technological advancements served as precursors to many modern inventions. Major critics who feared for the impersonal, mechanised direction of society during the revolution led to the Historicist movement that comprised of artistic styles aimed to emphasise the importance of history and meaning in art (“The Arts & Crafts Movement”). One of the main movements confining Historicism is the Arts & Crafts Movement, founded in Britain around 1860, which sought to reunite creativity and manufacturing in both fine and applied arts. Admired for its use of high quality materials and focus on functionality in design, the movement was spread to the United States in the 1890s and lasted until the 1920s. However, distinguishable attitudes were observed between Arts & Crafts artists and designers from the two places. While those in Britain saw the role of the machine in the creative process as a threat to quality of art, American artists saw it as an advantage for mass production and therefore a better market tool, rather than a hindrance to quality.

The advent of the Arts & Crafts Movement led to Bauhaus, arguably the most influential modernist art school of the 20th century founded in Weimar in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius (Museum & Digital Media, 2013). The Bauhaus came as a reaction to how the First World War had disrupted social values in the western world, as well as how industrialisation had made production methods inefficient. Its approach to teaching and understanding art’s relationship to society and technology attracted some of the key features of Modernism, and had a major impact in both Europe and the United States even after its closure. Also aimed to reunite creativity and manufacturing to revive both soul and purpose in art and products in society, artists sought to focus on the basic elements to make things convenient and accessible for people again, thus beginning a search to redefine constants in design such as shape, space, colour and movement (“Bauhaus Movement”). This resulted in a new market for design, the most innovative invention being the cantilever chair, with two legs instead of four, first designed in 1927 by Dutch architect Mart Stam. Modeled after a recent design innovation, the use of tubular steel for furniture pioneered by Marcel Breuer at the Bauhaus, the chairs appeared visually and physically light, demonstrating the Modernist goal of weightlessness and transparency (Museum & Digital Media, 2013).

As observed, the reactions to the Industrial Revolution provided wonders for people, where inventions created helped to improve the efficiency of people’s lives. Additionally, newly-efficient travels from steam engines also made way for trade boosts, as different groups of people were able to come into contact, thus allowing for more exchange of ideas and access to new technology in different places. For instance, the start of trades between Japan and Europe allowed for the aesthetic and philosophies of Japanese design to become popular, leading to the rise of Japanosim, the introduction of Japanese iconography and concepts into European art and design (“Japonism Movement”). One such example is how artists in search of new alternatives to the Renaissance tradition of illusionistic painting were attracted to the bright colours and new perspectives of the Ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock prints, such as unique cropping and contrasts of objects near and far. As a result of such interconnection, there was also competition to produce better and more attractive design, therefore improving design standards across the world.

Hence, in spite of causing great social issues between classes of the society, the Industrial Revolution was the reason for heavy advancement in the globalisation of art and design, pushing for innovations that can still be observed in today’s modern inventions.

1,469 words

Works Cited

Bauhaus Movement. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.theartstory.org/movement-bauhaus.htm#concepts_and_styles_header

Bellis, M. (n.d.). Meet Samuel Crompton: Inventor of the Spinning Mule. Retrieved September

1, 2018, from https://www.thoughtco.com/spinning-mule-samuel-crompton-1991498

Bellis, M. (n.d.). Richard Arkwright, Textile Revolutionary. Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.thoughtco.com/richard-arkwright-water-frame-1991693

Britannica, T. E. (2018, April 11). Industrial Revolution. Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution

Industrial Revolution. (2009). Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolutionn

Japonism Movement (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.theartstory.org/movement-japonism.htm

Museum, A., & Digital Media. (2013, January 31). Modernism: Building Utopia. Retrieved

September 1, 2018, from http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/modernism-and-the-new/

Newcomen’s steam revolution. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/discovering/famous/thomas_newcomen.shtml

The Arts & Crafts Movement. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.theartstory.org/movement-arts-and-crafts.htm

The Spinning Jenny: A Woolen Revolution. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2018, from

https://www.faribaultmill.com/pages/spinning-jenny