Month: November 2015

Final catalogue entry- Chinoiserie wallpaper

Britain (ar.1760s)

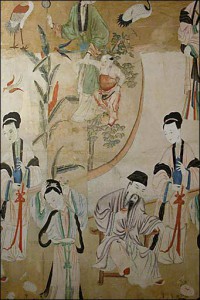

Pictures depicting large emblematic male and female figures in garden settings used as wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room in Saltram Palace

Ink on mulberry paper

National Trust Inventory No. 872998

Exhibition: Chinoiserie Gallery 2015

Chinoiserie reflects fanciful European interpretations of Chinese styles that used for furniture, pottery, textiles, interiors and garden design. Since early 17th century, craftsman draw sources from decorative forms found on imported goods from China such as cabinets, porcelain vessels, and embroideries.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Chinese craftsman and workshops start to create hand-painted wallpapers that were specifically made for exportation to the European market, and by the early 19th century no European palace was complete without a Chinoiserie room. Some extraordinary examples can still be seen in the Brighton Pavilon, Saltram, Sans Souci, Chateau Chantilly and Nostell Priory. The example we using here is from the Chinese room of Saltram Palace, which is a dressing room.

Chinoiserie wallpaper was commonly used in bedroom, dressing room and drawing room. It seems to have been rare, at least in Britain, for Chinese wallpaper to be used in the ‘masculine’ or formal areas of a house. Distinct from the state apartments and great rooms associated with the male head of the household, ‘feminine’ areas such as bedrooms, dressing rooms and drawing rooms seem to have been poised between the private and the public sphere. From the early eighteenth century onwards there appears to have been a tendency to link orientalism, femininity and sociability, as women use their chinoiserie styled dressing room to host their social activities. Therefore, apart from being a personal taste, chinoiserie interior shows strong famine characteristics. As Elizabeth Montagu pointed out ‘I assure you the dressing room is now just the female of the great room, for sweet attractive grace, for winning softness, for le je ne sais quoi it is incomparable’

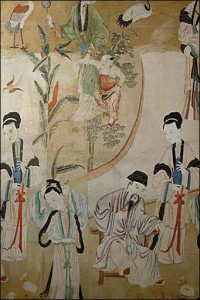

This wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room, painted on mulberry paper, is probably the oldest at Saltram, dating from the early eighteenth century, and depicts elegant people in a garden setting. Multiple copies of two Chinese hand-colored prints that have been hung in alternating pairs cover the Main wall of the room. The pictures are first printed on paper and then being colored by hand. The printing often extends beyond the outlines to include various other details. Repeated elements on some painted wallpapers suggests that they were produced by the meticulously tracing motifs from a common reference.

The most common procedure of hanging wallpaper was to stretch canvas or another open-weave fabric across the bare wall and nail it down onto wooden battens, then to size it and to cover it with a lining of individual sheets of European hand-made paper, and finally to attach the Chinese paper on top. If the drops did not quite cover the walls, the paper hangers would add border papers, unobtrusively insert sections of wallpaper taken from elsewhere or add new, extended skies. The greater width of Chinese wallpapers and the different reaction of Chinese paper to wallpaper paste presented additional challenges. In their advertisements paper hangers would therefore explicitly and proudly mention their ability to hang Chinese wallpaper.

In Figure 1,2,3, the skillful way in which the joins between the prints have been disguised, by cutting off the top margins around certain motifs and by the addition of certain cut-out motifs, suggests the involvement of a professional paper hanger.

Looking at the wallpaper, we realized that the painting is excitingly exotic, and yet it included elements that have been comfortingly familiar to the western eye. Chinese artists applied techniques and devices originally derived from western painting. During the late Ming and early Qing periods (roughly equivalent to the seventeenth century) some western illusionistic techniques like linear perspective, chiaroscuro and the depiction of interconnected spaces were introduced to China by Jesuit painters working at the imperial court and through the circulation of western prints. These techniques also appear in Chinese wallpaper or pictures used as wallpaper, especially in the depiction of volumetric shading in costumes and perspective and spatial recession in architecture.

Apart from the enduring popularity of these wallpapers, their physical survival is an equally astonishing phenomenon. Inevitably the papers have aged, not least as a result of use and imperfect environments. Typical deterioration and conservation challenges include delamination and staining of the paper, fading and localised flaking of certain pigments, inappropriate repairs and loss caused by the grazing of silverfish. However, the conservation of Chinese wallpapers in the west has developed considerably over the last few decades. By the early 1960s the wallpaper had become detached from the wall in places, and conservation treatment (including relining) was carried out by C.P. Sharpe of London in 1962.The scheme was removed from the walls, treated and relined by Merryl Huxtable and Pauline Webber in 1987, in conjunction with G. Jackson and Sons.

Bibliography:

- ISBN 978-0-7078-0428-6 © 2014 National Trust. Registered charity no. 205846 Text by Emile de Bruijn, Andrew Bush, Dr Helen Clifford Edited by Claire Forbes Designed by LEVEL • levelpartnership.co.uk

- To cite this article: Vanessa Alayrac‐Fielding (2009) ‘Frailty, thy name is China’: women, chinoiserie and the threat of low culture in eighteenth‐century England, Women’s History Review, 18:4, 659-668, DOI: 10.1080/09612020903112398 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09612020903112398

Final wall text- team 7

Team 7 – Chinoiserie: Behind the Sheets

Fiona, Azmeera, Peng Cheng and Yu Wei

Wall Text:

Chinoiserie are Chinese products meant for exportation by the local manufacturers. In order, to suit the preferences of foreign buyers, Chinese craftsman added patterns that were not authentic to Chinese products at that time in order to seem more appealing. Due to wave of success in these Chinese export wares in Britain, there were many British craftsmen that imitated the Chinese style to produce “pseudo-Chinese” products, later called this style was coined Chinoiserie. These exports started in the 17th century and expanded dramatically after two decades into the 18th century.

During the 18th century, Baroque and Rococo Styles were also popular, thus it was inevitable that Chinoiserie has both style incorporated. It is uncertain that Chinoiserie had inspired some great Rococo styled furnishings, but the mix of east and west was evident in Chinoiserie products.

Chinoiserie often features extensive gilding and lacquering for furniture, the use of blue and white in the porcelain products. All their products usually are asymmetrical with oriental figures and motifs such as cranes, willows and clouds. John MacKenzie pointed out: ‘Chinoiserie, the construction of an imaginary Orient to satisfy a western vision of human elegance and refinement within a natural and architectural world of extreme delicacy, was as much a product of Chinese craftsmen as of the West’ These products allowed westerners who never entered China develop this idea of fantastic foreign land and fall in love with the imaginary that were crafted.

Even though the exoticism of Chinoiserie was distinct, it was more directed more for the interest of the female population. There were some products that were directly catered for women consumption as it was rumoured that traders often bring Chinoiserie as souvenirs for their wives from the Canton Trade.

However, Chinoiserie was never appreciated by the high society as art but instead viewed as a threat that may lower the standards of arts and culture. This was mostly due to the fact that Chinoiserie often lack depth in meaning and focus on the idea of surface beauty. Furthermore, Chinoiserie was a representation of meaningless vanity, indulgence, and luxury.

Our Gallery, Chinoiserie: Behind the Sheets takes visitors on a trip to unveil the more sophisticated and private side of Chinoiserie which was deemed as low cultured. Even though Chinoiserie was considered frivolous, it had nevertheless empowered woman with distinct set of physical product.

As women had less opportunities to be in contact of the real arts, men used their access of knowledge and appreciation of ancient art to stigmatise women to a low and deviant form of art that anyone, with or without education, can appreciate. In other words, Chinoiserie might be used as a social order to keep the existing powers of elites that controls artistic values. However, the general public had turned a blind eye that Chinoiserie was the stepping stone for the all genders to be in touch with art then soon politics and power of west and east. In a patriarchal society then, women was often seen as devious manipulators that can potentially fling society into disorder, people often forget that ideals and politics has nothing to do with gender in the first place. Thus, Chinoiserie played a huge role to blurring gender roles at that time.

final objects label-Chinoiserie wallpaper

Object label:

Pictures depicting large emblematic male and female figures in garden settings used as wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room at Saltram National Trust Inventory No. 872998

Around 1760s

The wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room is probably the oldest at Saltram. It is painted on mulberry paper, depicting elegant people in a garden setting. The pictures are printed on paper in black and white and then coloured by hand.

The scheme is made up of multiple copies of two Chinese hand-coloured prints. 20 alternating pairs of prints were mounted on a textile lining. The joins between the prints have been disguised by skillful paper hanger, who cuts off the top margins around certain motifs and the addition of certain cut-out motifs proves their professionalism. The partition was decorated in a slightly different way, with the addition of large figures cut from other prints, and it appears to have been inserted into the room slightly later. Some colours have faded, particularly in the background.

In this picture, we can see that these Chinese wallpaper are not used alone, they are often complemented by ceramic dolls. Both figures in the painting and the dolls are dressed in the Chinese elegant robe and wearing the same kind of hairstyle. The depiction of these elegant figures probably reveals the life of Chinese high social classes, but it could also be a fancy story that made up to satisfy the curious westerners. Women decorated their bedroom and dressing room with these wallpapers and imagine about the far oriental world. Though their imagination maybe totally different from the real China, it was their great pleasure at that time.

Furthermore, if we look even closer, we realized the image of the plants on the wallpaper are not the same, they are several kinds of plants, and they are probably not from the same location and may not even grow in same climate. Since the paperhanger does these additions of images of plants, we could guess that the paper hangers had never been to China before, though they are good at deal with these Chinese wallpaper. Their understanding of Chinoiserie style could be only according to the tales from the merchants and traveller at that time and images that being exported to Europe.

Reflection on the final exhibition

This is a valuable experience that we learn art history through a process of organizing an artifact exhibition.

At the beginning, we have some difficulties in deciding our topics and objects. Then we finally decided to study the Chinoiserie

topic. We went through many research materials and we realised that Chinoiserie style was closely tied to female. Therefore,we would like to approach this topic by discussing the relationships between Chinoiserie and Female at 18th Century.

During the preparation of the gallery proposal, we went through many argument about what objects we need to put inside the gallery. At first, we are stunned by the great amount of Chinoiserie subject that available for our research, but we need to narrow down our research and decide on only 4 objects. Since we want to talk about “Chinoiserie and Female”, bedroom would be a great place and scenario for us to start. Because at that time, woman are most likely all housewives, the place they could control would be their bedroom or dressing room. Therefore, by studying their chinoiserie styled bedroom, we could better understand their partiality of Chinoiserie style.

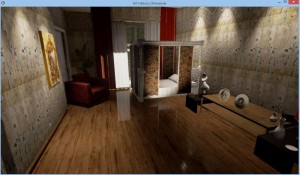

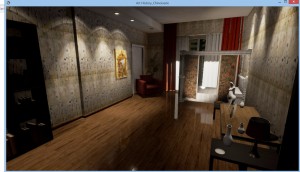

This is our final outcome of the gallery proposal. As you can see we used computer model to simulate the actual gallery.

This is the result after we considered many factors. First of all, I think gallery need to show the artefact in the condition that best represents their function and culture, provide short and precise information for the visitors. Secondly, gallery need to protect the artefact. Thirdly, gallery need to engage the audience through visual, auditory,tactile or sensual stimulators. Fourthly, gallery need to provide souvenirs or something that could be take away by the visitors.

Hence, we decide to use computer model to best represent the real gallery, because we could model everything according to our need, especially the lightings. As you can see from above picture, specific lightings are designed to illuminate the artefacts and walltext. Besides, as we are doing in computer, we could model the surface according to the real gallery material. For example, the floor are set as wooden floors.

Furthermore, this kind of computer interactive model could be the future form of gallery. Since we may not be able to afford to travel to certain country to visit the museums there, it would be great for people to “visit”the gallery online. Now we could only look at pictures that objects are isolated and against white background, it does not give us the right atmosphere to appreciate the objects. Hence, it would be great that people can visit the museum website and have the opportunity to play with interactive games such as our project. The visitor could look around the online gallery which are modelled exactly the same as the actual physical model. Isn’t that cool?

All in all, through this project, I learned to approach art history in a new way. I know how to narrow down and focus on one problem when we try to understand certain culture. This trained me on selecting information and transfer information into shorter but effective message towards the audience.

Team7- Chinoiserie wall paper – Catalogue Entry

Britain (ar.1760s)

Pictures depicting large emblematic male and female figures in garden settings used as wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room in Saltram Palace

Ink on mulberry paper

National Trust Inventory No. 872998

Exhibition: Chinoiserie Gallery 2015

Chinoiserie reflects fanciful European interpretations of Chinese styles that used for furniture, pottery, textiles, interiors and garden design. Since early 17th century, craftsman draw sources from decorative forms found on imported goods from China such as cabinets, porcelain vessels, and embroideries.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Chinese craftsman and workshops start to create hand-painted wallpapers that were specifically made for exportation to the European market, and by the early 19th century no European palace was complete without a Chinoiserie room. Some extraordinary examples can still be seen in the Brighton Pavilon, Saltram, Sans Souci, Chateau Chantilly and Nostell Priory. The example we using here is from the Chinese room of Saltram Palace, which is a dressing room.

Chinoiserie wallpaper was commonly used in bedroom, dressing room and drawing room. It seems to have been rare, at least in Britain, for Chinese wallpaper to be used in the ‘masculine’ or formal areas of a house. Distinct from the state apartments and great rooms associated with the male head of the household, ‘feminine’ areas such as bedrooms, dressing rooms and drawing rooms seem to have been poised between the private and the public sphere. From the early eighteenth century onwards there appears to have been a tendency to link orientalism, femininity and sociability, as women use their chinoiserie styled dressing room to host their social activities. Therefore, apart from being a personal taste, chinoiserie interior shows strong famine characteristics. As Elizabeth Montagu pointed out ‘I assure you the dressing room is now just the female of the great room, for sweet attractive grace, for winning softness, for le je ne sais quoi it is incomparable’

This wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room, painted on mulberry paper, is probably the oldest at Saltram, dating from the early eighteenth century, and depicts elegant people in a garden setting. Multiple copies of two Chinese hand-colored prints that have been hung in alternating pairs cover the Main wall of the room. The pictures are first printed on paper and then being colored by hand. The printing often extends beyond the outlines to include various other details. Repeated elements on some painted wallpapers suggests that they were produced by the meticulously tracing motifs from a common reference.

The most common procedure of hanging wallpaper was to stretch canvas or another open-weave fabric across the bare wall and nail it down onto wooden battens, then to size it and to cover it with a lining of individual sheets of European hand-made paper, and finally to attach the Chinese paper on top. If the drops did not quite cover the walls, the paper hangers would add border papers, unobtrusively insert sections of wallpaper taken from elsewhere or add new, extended skies. The greater width of Chinese wallpapers and the different reaction of Chinese paper to wallpaper paste presented additional challenges. In their advertisements paper hangers would therefore explicitly and proudly mention their ability to hang Chinese wallpaper.

In Figure 1,2,3, the skillful way in which the joins between the prints have been disguised, by cutting off the top margins around certain motifs and by the addition of certain cut-out motifs, suggests the involvement of a professional paper hanger.

Looking at the wallpaper, we realized that the painting is excitingly exotic, and yet it included elements that have been comfortingly familiar to the western eye. Chinese artists applied techniques and devices originally derived from western painting. During the late Ming and early Qing periods (roughly equivalent to the seventeenth century) some western illusionistic techniques like linear perspective, chiaroscuro and the depiction of interconnected spaces were introduced to China by Jesuit painters working at the imperial court and through the circulation of western prints. These techniques also appear in Chinese wallpaper or pictures used as wallpaper, especially in the depiction of volumetric shading in costumes and perspective and spatial recession in architecture.

Apart from the enduring popularity of these wallpapers, their physical survival is an equally astonishing phenomenon. Inevitably the papers have aged, not least as a result of use and imperfect environments. Typical deterioration and conservation challenges include delamination and staining of the paper, fading and localised flaking of certain pigments, inappropriate repairs and loss caused by the grazing of silverfish. However, the conservation of Chinese wallpapers in the west has developed considerably over the last few decades. By the early 1960s the wallpaper had become detached from the wall in places, and conservation treatment (including relining) was carried out by C.P. Sharpe of London in 1962.The scheme was removed from the walls, treated and relined by Merryl Huxtable and Pauline Webber in 1987, in conjunction with G. Jackson and Sons.

Bibliography:

1. http://global.britannica.com/art/chinoiserie

2. ISBN 978-0-7078-0428-6

© 2014 National Trust. Registered charity no. 205846 Text by Emile de Bruijn, Andrew Bush, Dr Helen Clifford Edited by Claire Forbes

Designed by LEVEL • levelpartnership.co.uk

3. To cite this article: Vanessa Alayrac‐Fielding (2009) ‘Frailty, thy name is China’: women, chinoiserie and the threat of low culture in eighteenth‐century England, Women’s History Review, 18:4, 659-668, DOI: 10.1080/09612020903112398 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09612020903112398

Team7 – Chinoiserie – Wallpaper – object label

Pictures depicting large emblematic male and female figures in garden settings used as wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room at Saltram National Trust Inventory No. 872998

Around 1760s

The wallpaper in the Chinese Dressing Room, painted on mulberry paper, is probably the oldest at Saltram, dating from the early eighteenth century, and depicts elegant people in a garden setting. The scheme is made up of multiple copies of two Chinese hand-coloured prints. On the main walls of the room the two prints have been hung in alternating pairs. The pictures are printed on paper and finished by hand in black ink and colour. They were mounted on a textile lining. There are about 20 alternating pairs of prints on the main walls, and more on the partition. The skillful way in which the joins between the prints have been disguised, by cutting off the top margins around certain motifs and by the addition of certain cut-out motifs, suggests the involvement of a professional paper hanger. The partition was decorated in a slightly different way, with the addition of large figures cut from other prints, and it appears to have been inserted into the room slightly later. Some colours have faded, particularly in the backgrounds.