DR. LEVINE’S MAGIC UNDERWEAR resembled bicycle shorts, black and skintight, but with sensors mounted on the thighs and wires running to a fanny pack. The look was part Euro tourist, part cyborg. Twice a second, 24 hours a day, the magic underwear’s accelerometers and inclinometers would assess every movement I made, however small, and whether I was lying, walking, standing or sitting.

James Levine, a researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., has an intense interest in how much people move — and how much they don’t. He is a leader of an emerging field that some call inactivity studies, which has challenged long-held beliefs about human health and obesity. To help me understand some of the key findings, he suggested that I become a mock research trial participant. First my body fat was measured inside a white, futuristic capsule called a Bod Pod. Next, one of Dr. Levine’s colleagues, Shelly McCrady-Spitzer, placed a hooded mask over my head to measure the content of my exhalations and gauge my body’s calorie-burning rate. After that, I donned the magic underwear, then went down the hall to the laboratory’s research kitchen for a breakfast whose calories were measured precisely.

A weakness of traditional activity and obesity research is that it relies on self-reporting — people’s flawed recollections of how much they ate or exercised. But the participants in a series of studies that Dr. Levine did beginning in 2005 were assessed and wired up the way I was; they consumed all of their food in the lab for two months and were told not to exercise. With nary a snack nor workout left to chance, Dr. Levine was able to plumb the mysteries of a closed metabolic universe in which every calorie, consumed as food or expended for energy, could be accounted for.

His initial question — which he first posed in a 1999 study — was simple: Why do some people who consume the same amount of food as others gain more weight? After assessing how much food each of his subjects needed to maintain their current weight, Dr. Levine then began to ply them with an extra 1,000 calories per day. Sure enough, some of his subjects packed on the pounds, while others gained little to no weight.

“We measured everything, thinking we were going to find some magic metabolic factor that would explain why some people didn’t gain weight,” explains Dr. Michael Jensen, a Mayo Clinic researcher who collaborated with Dr. Levine on the studies. But that wasn’t the case. Then six years later, with the help of the motion-tracking underwear, they discovered the answer. “The people who didn’t gain weight were unconsciously moving around more,” Dr. Jensen says. They hadn’t started exercising more — that was prohibited by the study. Their bodies simply responded naturally by making more little movements than they had before the overfeeding began, like taking the stairs, trotting down the hall to the office water cooler, bustling about with chores at home or simply fidgeting. On average, the subjects who gained weight sat two hours more per day than those who hadn’t.

People don’t need the experts to tell them that sitting around too much could give them a sore back or a spare tire. The conventional wisdom, though, is that if you watch your diet and get aerobic exercise at least a few times a week, you’ll effectively offset your sedentary time. A growing body of inactivity research, however, suggests that this advice makes scarcely more sense than the notion that you could counter a pack-a-day smoking habit by jogging. “Exercise is not a perfect antidote for sitting,” says Marc Hamilton, an inactivity researcher at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

The posture of sitting itself probably isn’t worse than any other type of daytime physical inactivity, like lying on the couch watching “Wheel of Fortune.” But for most of us, when we’re awake and not moving, we’re sitting. This is your body on chairs: Electrical activity in the muscles drops — “the muscles go as silent as those of a dead horse,” Hamilton says — leading to a cascade of harmful metabolic effects. Your calorie-burning rate immediately plunges to about one per minute, a third of what it would be if you got up and walked. Insulin effectiveness drops within a single day, and the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes rises. So does the risk of being obese. The enzymes responsible for breaking down lipids and triglycerides — for “vacuuming up fat out of the bloodstream,” as Hamilton puts it — plunge, which in turn causes the levels of good (HDL) cholesterol to fall.

Hamilton’s most recent work has examined how rapidly inactivity can cause harm. In studies of rats who were forced to be inactive, for example, he discovered that the leg muscles responsible for standing almost immediately lost more than 75 percent of their ability to remove harmful lipo-proteins from the blood. To show that the ill effects of sitting could have a rapid onset in humans too, Hamilton recruited 14 young, fit and thin volunteers and recorded a 40 percent reduction in insulin’s ability to uptake glucose in the subjects — after 24 hours of being sedentary.

Over a lifetime, the unhealthful effects of sitting add up. Alpa Patel, an epidemiologist at the American Cancer Society, tracked the health of 123,000 Americans between 1992 and 2006. The men in the study who spent six hours or more per day of their leisure time sitting had an overall death rate that was about 20 percent higher than the men who sat for three hours or less. The death rate for women who sat for more than six hours a day was about 40 percent higher. Patel estimates that on average, people who sit too much shave a few years off of their lives.

Another study, published last year in the journal Circulation, looked at nearly 9,000 Australians and found that for each additional hour of television a person sat and watched per day, the risk of dying rose by 11 percent. The study author David Dunstan wanted to analyze whether the people who sat watching television had other unhealthful habits that caused them to die sooner. But after crunching the numbers, he reported that “age, sex, education, smoking, hypertension, waist circumference, body-mass index, glucose tolerance status and leisure-time exercise did not significantly modify the associations between television viewing and all-cause . . . mortality.”

Sitting, it would seem, is an independent pathology. Being sedentary for nine hours a day at the office is bad for your health whether you go home and watch television afterward or hit the gym. It is bad whether you are morbidly obese or marathon-runner thin. “Excessive sitting,” Dr. Levine says, “is a lethal activity.”

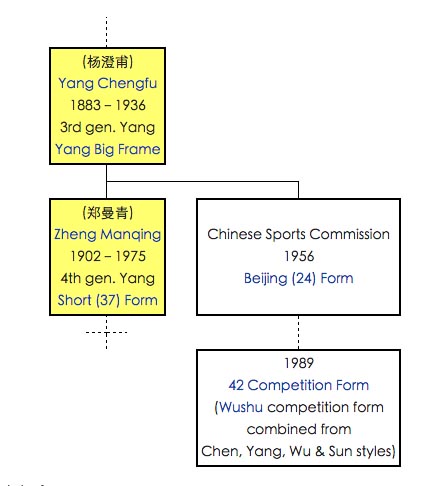

The good news is that inactivity’s peril can be countered. Working late one night at 3 a.m., Dr. Levine coined a name for the concept of reaping major benefits through thousands of minor movements each day: NEAT, which stands for Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. In the world of NEAT, even the littlest stuff matters. McCrady-Spitzer showed me a chart that tracked my calorie-burning rate with zigzagging lines, like those of a seismograph. “What’s that?” I asked, pointing to one of the spikes, which indicated that the rate had shot up. “That’s when you bent over to tie your shoes,” she said. “It took your body more energy than just sitting still.”

In a motion-tracking study, Dr. Levine found that obese subjects averaged only 1,500 daily movements and nearly 600 minutes sitting. In my trial with the magic underwear, I came out looking somewhat better — 2,234 individual movements and 367 minutes sitting. But I was still nowhere near the farm workers Dr. Levine has studied in Jamaica, who average 5,000 daily movements and only 300 minutes sitting.

Dr. Levine knows that we can’t all be farmers, so instead he is exploring ways for people to redesign their environments so that they encourage more movement. We visited a chairless first-grade classroom where the students spent part of each day crawling along mats labeled with vocabulary words and jumping between platforms while reciting math problems. We stopped by a human-resources staffing agency where many of the employees worked on the move at treadmill desks — a creation of Dr. Levine’s, later sold by a company called Steelcase.

Dr. Levine was in a philosophical mood as we left the temp agency. For all of the hard science against sitting, he admits that his campaign against what he calls “the chair-based lifestyle” is not limited to simply a quest for better physical health. His is a war against inertia itself, which he believes sickens more than just our body. “Go into cubeland in a tightly controlled corporate environment and you immediately sense that there is a malaise about being tied behind a computer screen seated all day,” he said. “The soul of the nation is sapped, and now it’s time for the soul of the nation to rise.”