When we were first assigned our teams, I didn’t know how everyone’s work style would be like or how we would work well with one another. However, over the semester, I had a lot of fun working with my teammates (:

We had a little trouble deciding on what topic to choose and even when we chose our topic, we had to decide on what to focus on. Each of us had different ideas and different perspectives on the topic, but ultimately we decided to take the topic out of the box and extend on the topic much further, therefore, instead on using maps as a focus on Mapping Asia, we looked at trade routes instead.

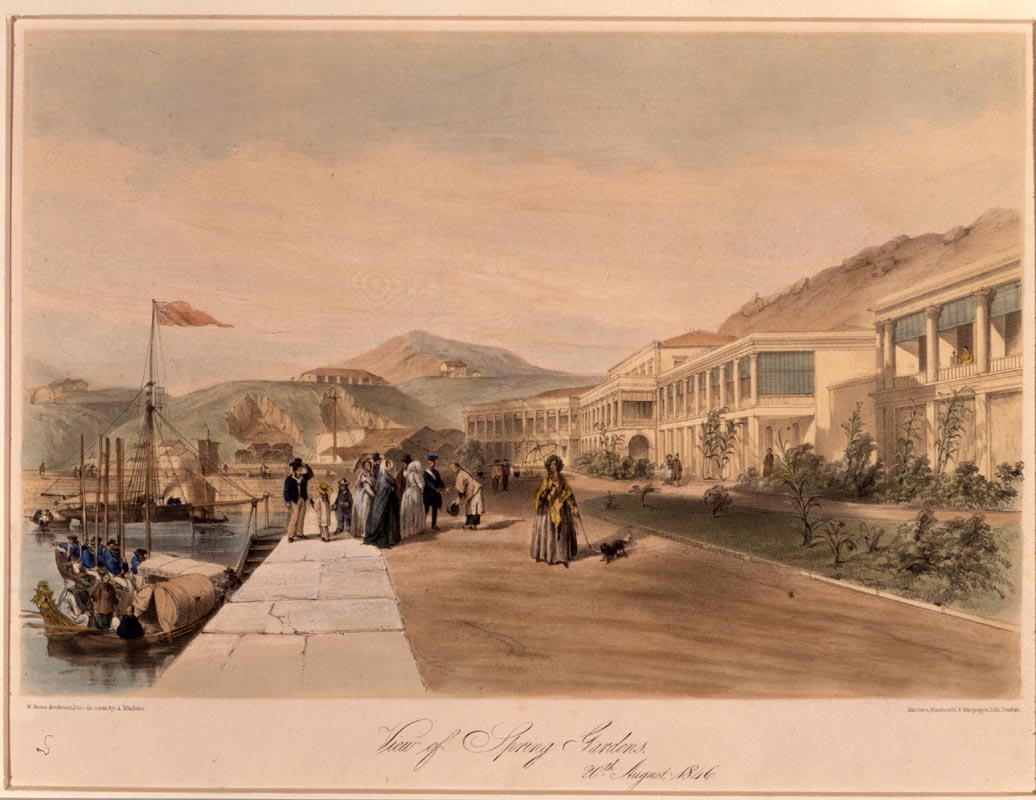

Each of us looked at the Western powers, those that travelled to Asia and colonised countless numbers of countries. We researched, individually, on which colonial power was ideal for our group. Eventually, we settled on Britain as we thought that it was interesting how they became so influential in Asia despite being the last of the colonial powers to enter Asia. Then came finding our objects! We each took a country, Singapore, Burma, India, and Hong Kong, and did research on art pieces from the individual countries. Personally, I had a lot of trouble finding colonial pieces from Hong Kong. I didn’t want to pick something that was already shown in class as I felt I should look for something that would give a fresh perspective on colonial Hong Kong and also because I thought I would be able to learn something more from a new piece.

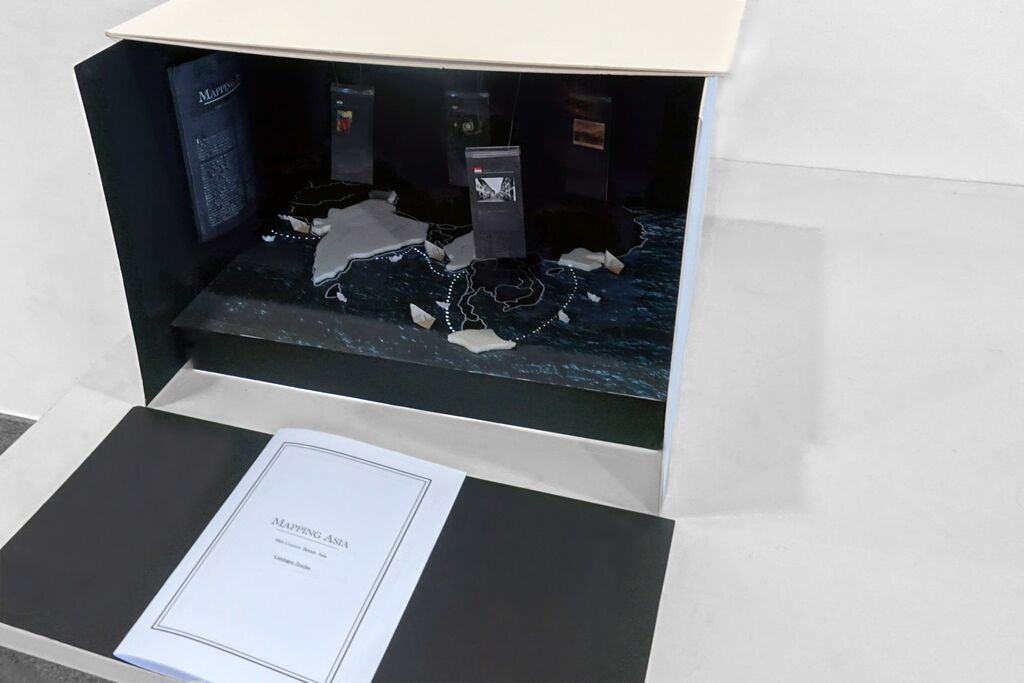

Once we decided on our pieces, we also had to link them together. Besides being art works that came out of British Asia, what else did they show, and how were we going to display them. All of us had different ideas on the exhibit and the overall theme, and after discussing it over and over again, throwing new ideas on the table every time, we finally settled on our final piece.

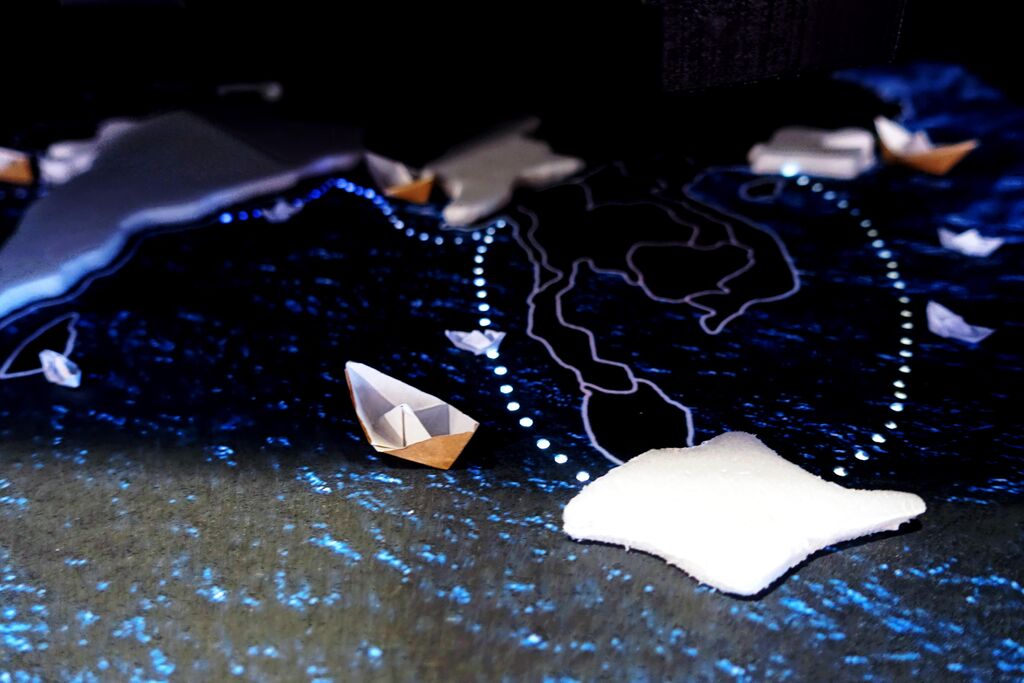

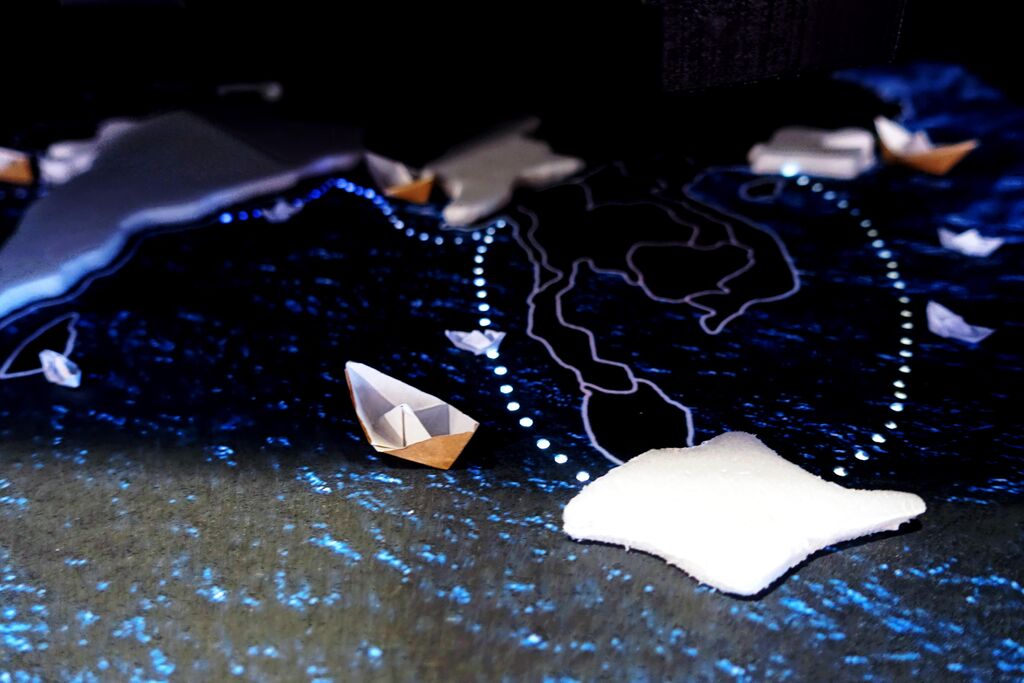

The presentation was fun and also nerve-wrecking, having to keep to the time limit was hard but it was also good preparation for FYP. Our consultation actually helped us the most in finalising the details in our model exhibit. While we initially only wanted to have the country platforms, we didn’t think about the surroundings. After the consultation, we finalised our design and began working on the physical piece.

After we were done making our piece, and after the final presentation, we were given excellent feedback and even realised that there were other ways they we could have improved on our exhibit layout, like cutting out the bottom of the cellfoam to make the platform light up to give the impression that the platforms were lit up.

In conclusion, I truly enjoyed this course as well as working with my teammates. This course has really opened my eyes to the reality of the colonial empires in Asia. It was the immense research on the two presentations in the course that really exciting. It was so difficult to find certain things but the knowledge I earned in the process was incredibly rewarding.