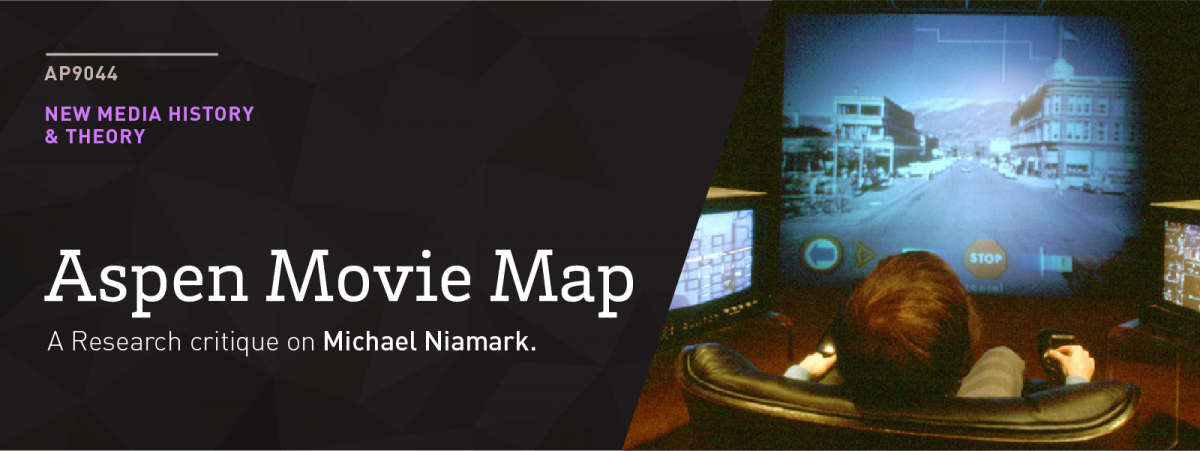

The Aspen Movie Map, created by Michael Naimark and his team at MIT, represents one of the forefronts of interactive video computing technology that was in rapid development during the late 70s. Seen as a revolutionary example of hypermedia, the movie map was perhaps the first interactive platform of it’s kind to utilize non-linear live-action content to create an interactive experience. Many technologist and artists during this period were also actively pursuing the idea of a platform that would allow the perusal of interconnected media in a way that was non-linear and associative. The basis for this idea can be traced back to the concept of the Memex, first proposed by Vannevar Bush in his essay, As We May Think back in 1945.

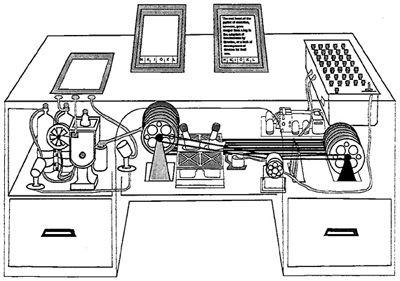

In his discourse, Bush lamented the lack of a system that enabled humans to easily reference the collective knowledge of the entire race in a quick and intuitive manner. He described the laborious process of index based referencing and how it was an unnatural way for the human mind to process information. “The human mind […] operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts.” He envisioned a system of interlinked documents and media that would behave similarly to how humans connected thoughts, ideas and concepts in a chain-like fashion. While this concept predates hypertext, it most definitely behaves similarly on a conceptual level.

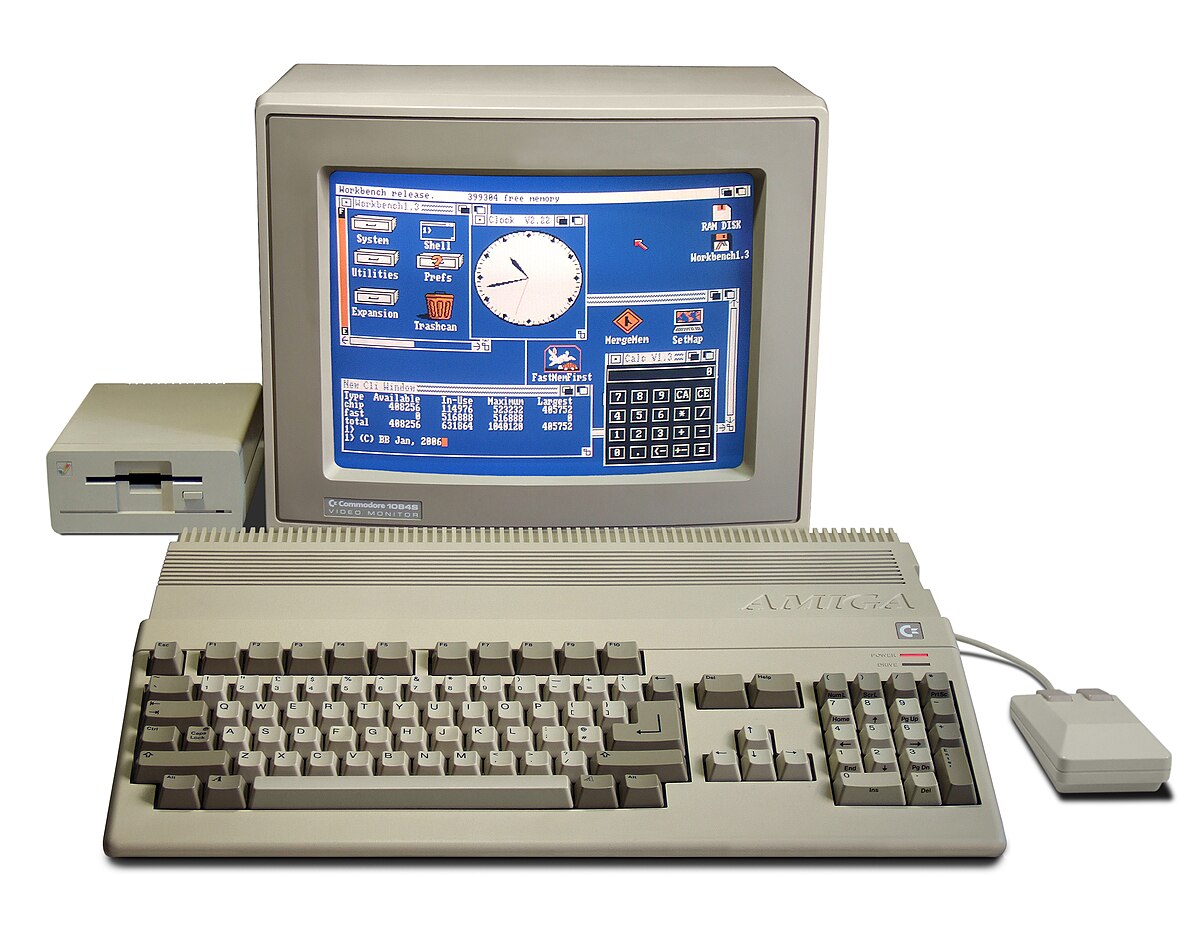

Bush also envisioned that the system would take the form of a desk, a visual metaphor for graphical computing that will still use today. While this might have been a subconscious decision, it would stand to reason that Bush would have wanted the interactions with the Memex to be as similar to what people were already doing in their day to day lives. This would have greatly helped to reduce the friction in adopting such a radically new way of working and thinking. To the more technologically astute, this rudimentary description of Bush’s would remind one of the Graphical User Interface (GUI) that was eventually developed by Alan Kay and his team over at Xerox PARC. The Memex then, can be considered as the philosophical ancestor of all of modern computing as we know it; from the way in which content is non-linear and interconnected, to the way users went about interacting with them.

In a similar vein to the Memex, the Aspen Movie Map is another example of technology that leverages hypermedia to more closely imitate real world experiences. While the Memex was interested in creating a better user experience for the perusal of documents, the Aspen Movie Map proposes a better system than traditional two-dimensional maps to make sense of positional and spatial data. While maps have been used by human society as an aid to understand spatiality for the longest time, it still requires a certain degree of mental gymnastics before the two-dimensional map on the drawing can be re-interpreted to guide one through a three-dimensional reality such as the one we all live in.

However, what makes the Movie Map more pertinent in media history, is that instead of having users sit through an ‘on-rails’ experience where they are brought along for the ride, the Movie Map allows for people to travel through the space and wander around the city of Aspen, Colorado in a similar fashion to real life. Niamark termed it “surrogate travel”, where he served as the surrogate traveller for viewers to later go through the same journeys digitally. The usage of hypermedia allowed the team to create a richer experience for users, providing them the option to enter buildings, interact with restaurant menus, and even change between seasons. To the modern person, this would seem extremely similar to the Street View feature of Google Maps. The user experience from the Interface, coupled with the use of live-action footage, creates a sense of immersion for users of the movie map that far supersedes the experience of making sense of a traditional cartographical diagram.

The modern world is extremely indebted to hypermedia and metaphorical visual computing for laying the ground work for our present day digital existence. From creating non-linear information portals that provide us with knowledge, to visual interfaces that rely on intuition to operate these portals and devices, Vannenar Bush, Michael Niamark and Alan Kay have really pushed the human race forward such that we may truly go about our lives as we may think.