As They Might Think

Envisioning Media Art In The Age of Machine Intelligence

Introduction

When Richard Wagner put forth his ideas for the Gesamtkunstwerk, he was concerned with the creation of a total artwork that would unify the various disciplines of art through theatre. The opera was seen as the pinnacle of artistic expression during the mid-to-late 19th century and it provided the perfect platform for Wagner to pursue his ideals. Introducing the darkened space and controlling how and what audiences saw, Wagner was one of the first to successfully execute on the concept of the “suspension of disbelief.” As we progressed along, creatives and technologists remained dedicated to furthering the “totalitizing experience of art.” The works of creators like John Cage and Nam Jun Paik began to explore the behavioral relationships between artist and observer; bringing into view cybernetic visions within the field of art.

Roy Ascott commented in his essay that modern art needed to offer “a high degree of uncertainty” and permit “a great intensity of participation.” Experiments into full body digital immersion in the 80s and 90s answered that call, and more. With the rise of head-mounted displays, binaural audio and sensory input devices, systems such as the VIEW at NASA Ames allowed artists to create “doorways to other worlds” that existed beyond the physical limitations of our own. Seminal virtual-reality works like Char Davies’ Osmose brought such worlds to life and formalized new relationships between audience and artwork. In effect, interactivity and immersion had now become key considerations in the construction of a gesamtkunstwerk — going so far as to say that it was essential now for these artworks to exist in the form of media art.

With these developments in technology, one could be excused for thinking that a pinnacle has been reached. What more can be done, given that it is now possible to transcend both body and mind into an altered state of reality? Indeed, there is more to be achieved. In the 30 years since the development of the VIEW system, technology, society and the way we interface with the world around us have shifted significantly. The rise of the internet and ubiquitous computing has forced us to reconsider our place amongst technology as well as its impact on our lives. Society has been reconditioned on a level that has not been witnessed since the Industrial Revolution and digital data has become the all encompassing common denominator of human society. Consequently, the total artwork of the present and future should take into account these cognitive shifts in societal behavior and derive new definitions of what constitutes the gesamtkunstwerk of the 21st century. Refik Anadol is one such artist whose works explore our relationship with technology, the merging of physical and digital space, and how data can be exploited as a medium to create profound media art experiences.

Rethinking Digital Immersion

A contemporary media artist who works across large varieties of digital media, much of Anadol’s works focus on site-specificity — choosing to create digital public art that leverage and accentuate the surrounding architecture. Anadol uses projections (both indoors and outdoors) as well as large scale screen installations to create immersive spaces that transport audiences into an imagined environment. As a media artist, designer and spatial thinker, Refik Anadol is also intrigued by the ways in which the transformation of contemporary art culture requires the rethinking of new aesthetics, techniques and most importantly, a dynamic perception of space. His works aim to create visually agnostic depictions that form a visual language capable of appealing to large groups of people; despite cultural backgrounds or aesthetic preferences.

The importance of space in Anadol’s works is also seen in his interpretation of it through his artistic expressions. By embedding media art into architecture, he questions the possibility of a future within which all human-made surfaces are informed in some shape or form, by the digital footprint that mankind leaves behind. Spatiality also informs how Anadol designs his viewers’ interactive experiences. His works cater towards eliciting the reactions and interactions of passers-by within unconventional spatial orientations, going against the established status quo of pursuing highly abstracted digital spaces to create immersion. Anadol’s works then, suggest all spaces and facades have the potential to be utilized as the media artists’ canvas; seemingly determined to prove that highly immersive spaces can in fact be achieved without resorting to the use of “The Ultimate Display“.

Data As A Medium

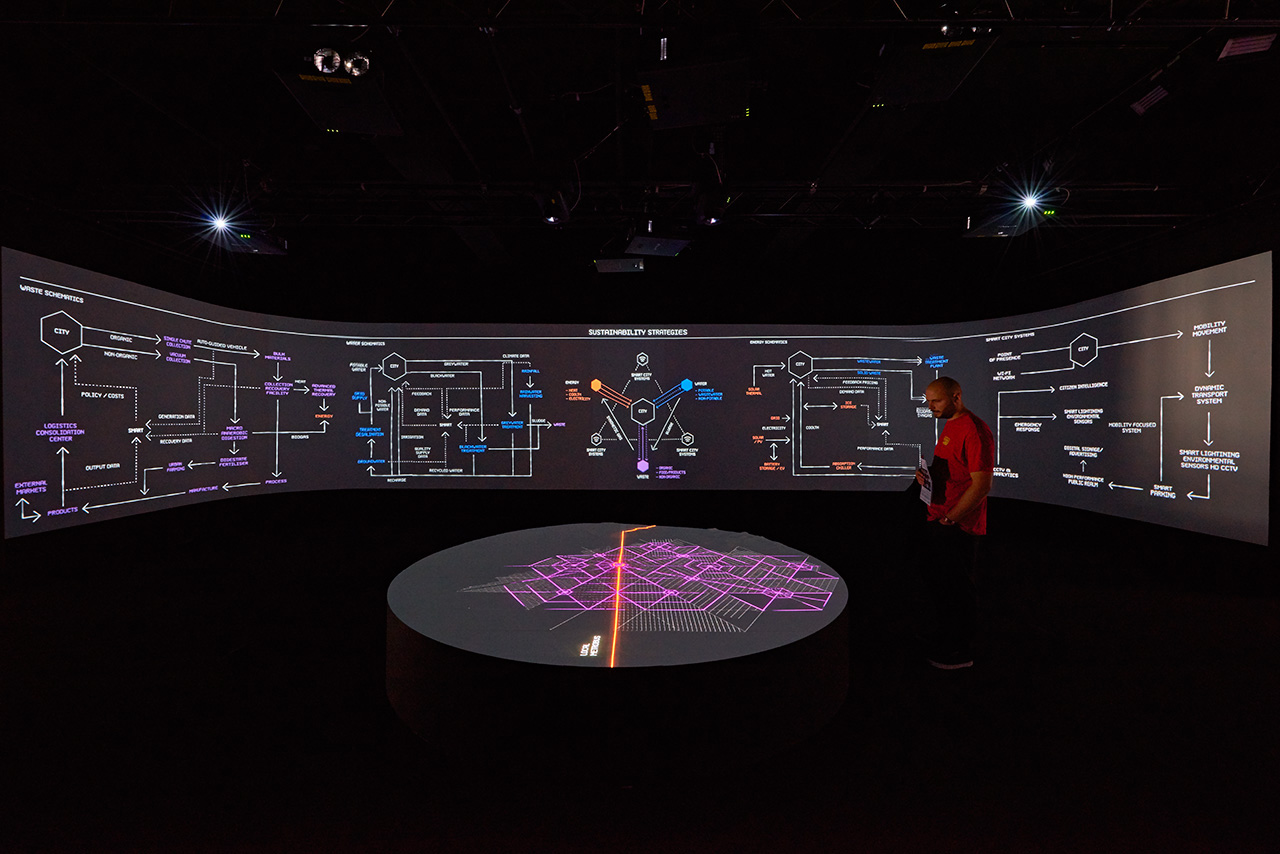

Refik Andol’s works and creative processes are based on and deeply influenced by technology: specifically generative data. As modern members of society, we are profligate with the creation of new data. In 2013, it was noted that 90% of all the data output ever made occurred over the span of 2 years (2011-2013). The pursuit of smart cities and the vision of embedded sensors within our built environment have contributed towards this exponential growth of data-generation. We now occupy living, evolving, self-aware cities, bristling with input devices that continuously monitor and provide a myriad of data feedback. Human society also produces large quantities of data through modes of self-expression such as social media and other computer mediated technologies. Often times, all of this data rarely sees the light of day; relegated to internal uses within the social groups, companies and government bodies that process them.

However, what if as creatives, one was to exploit these information sources and utilize these large quantities of unprocessed data to create new forms of expression? How do we negotiate the ever-fading distinction between our personas within the digital space and our “real” lives within the physical world? What if we were to question how our experience of space is changing now that digital objects ranging from smart phones and embedded sensors to urban screens have colonized our everyday lives. How have computer mediated technologies changed our conceptualizations of our everyday spaces, and how has our built environment embraced these shifting conceptualizations to accommodate these changes?

Through his work, Anadol tackles these questions; not by simply integrating media art into built forms, but by translating the logic of media technologies into spatial design itself. Data becomes the medium and the subject; the cause and the effect of trying to establish the gesamtkunstwerk of the 21st century. That said, how does one go about defining a new visual vocabulary for these types of works without resorting to the established visual practices of traditional data visualization.

During his talk at the Emergent Visions symposium, Refik Anadol addressed this specific concern when discussing his works. He elaborated that for creatives working with data, it was not enough to simply stop at data visualization. “We are not data scientists,” he remarked. Authenticity and accurate representation of the dataset was not always required, or maybe even useful in developing a visual outcome. Rather, Anadol encouraged creatives to attempt what he termed as data dramatization; to create a sense of empathy and derive emotion out of the data as opposed to presenting a cold, immutable tabulation of scientific findings. He argued that for data driven media art, the meaning of the work should be held in the poetics of the representation and not be derived from the source itself. This philosophy rings similar to Roy Ascott’s thoughts on telematic art where he put forth that “meaning is the product of interaction between the observer and the system, the content of which is a state of flux.”

The usage of data as a medium then introduces a new approach to thinking about media art. It calls into question the very paradigms that form the foundations guiding our understanding about the collection, storage and presentation of data in the creative practice. In this regard, Archive Dreaming by Refik Anadol serves as a potential candidate to further dissect and understand how we could go about building future “total artwork” experiences.

A New Reality for Old Knowledge

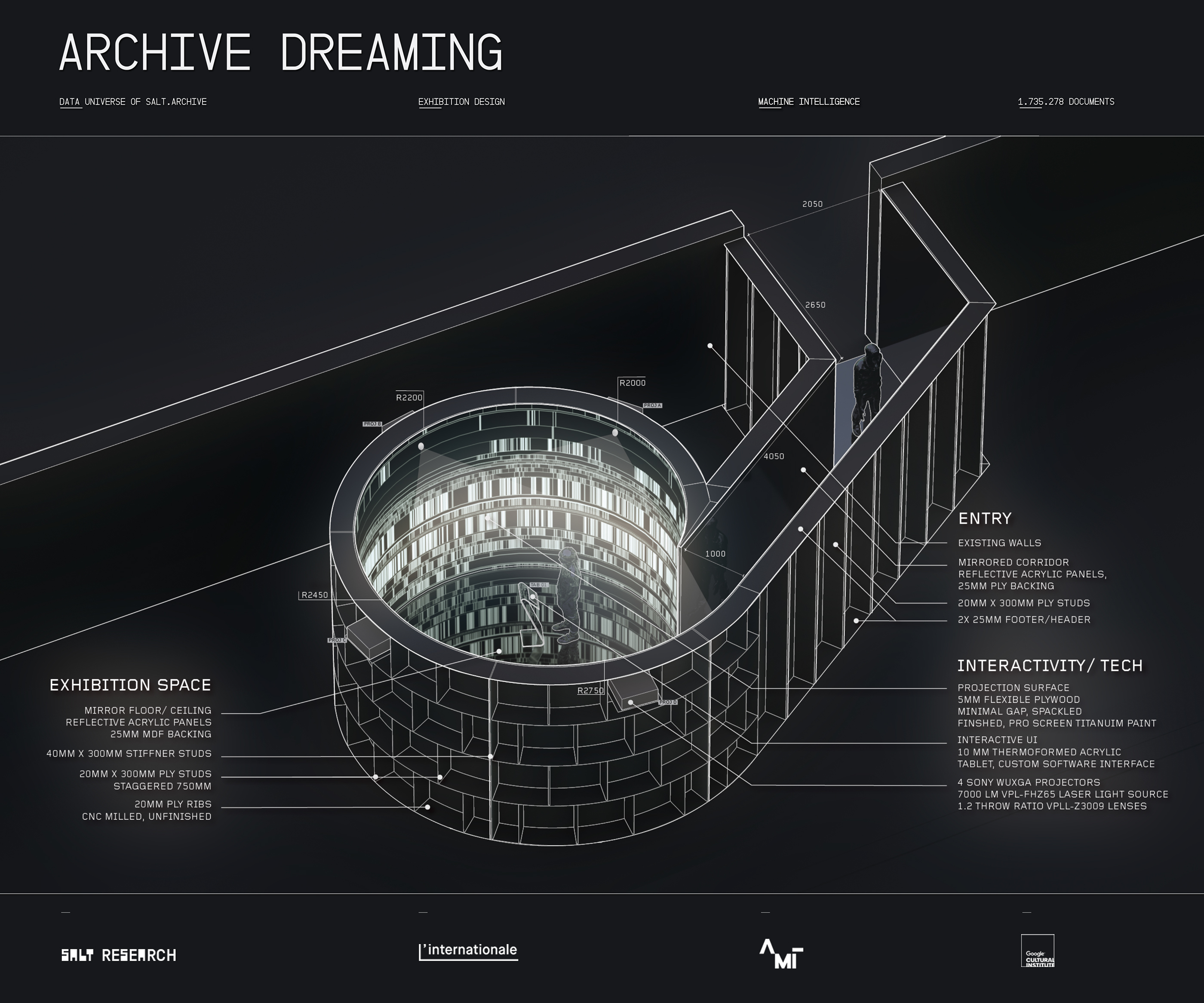

Archive Dreaming (2017) by Refik Anadol is a data visualization work installed at SALT Research in Istanbul, Turkey. Being a public art installation, the work was conceived as an alternative method for visitors to peruse and engage with the document collections of SALT Research. The facility comprises a specialized library and an archive of both physical and digital sources. Their collections include visual and textual sources on art history, the development of architecture and design in Turkey, as well as documents dealing with transformations in the region during the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic. Due to the significant age and frailty of most of these documents, large parts of the facility’s collections are housed in specialized, environment controlled rooms; reducing accessibility to large parts of the physical collection.

While other attempts at a such a project might have led to the creation of a photographic or micro-film database, Archive Dreaming takes the concept of an interactive archive much further. The most obvious and significant aspect of this work is in its use of physical space and architecture. The installation is designed to be a spatial experience. In the words of Anadol himself, the work is described as an effort to “deconstruct the framework of an illusory space [that transgresses] the normal boundaries of the viewing experience of a library”. The work was specifically conceptualized with the notion to significantly transform the experience of accessing a knowledge repository. The work was to be a “a three dimensional kinetic and architectonic space of an archive.”

The vision to create a new paradigm for archival access may seem bold and ambitious. However, much of these ideas can be traced back to the research and thought experiments conducted by artists and technologists during the 60s. Ivan Sutherland’s ‘The Ultimate Display‘ famously envisions a futuristic display system which takes the form of a room “within which the computer can control the existence of matter.”

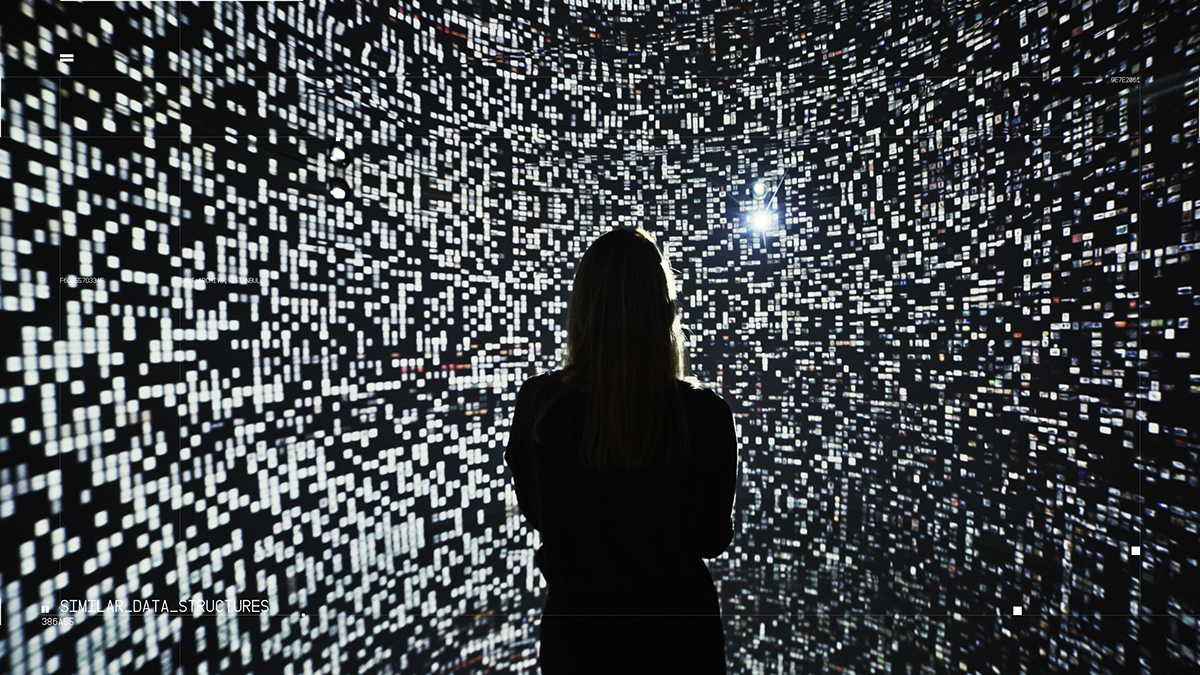

While we are still decades away from experiencing anything remotely close to his description, Sutherland’s essay made significant arguments towards how we could utilize immersive environments to augment our current assumptions of a particular subject matter. He claimed that by simulating other realities foreign to our current comprehension, “we can learn to know them as well as we know our own natural world.” Archive Dreaming in many regards, does precisely this. Data is no longer confined to a network terminal or pages of a book, instead transporting the viewer into the data-space of the archive itself. It reframes our established preconceptions of what a library should be and might perhaps even establish new methods for scholarly research. Much like what Osmose did for physical transcendence, Archive Dreaming could conceivable do the same for academia, as users physically engage with, negotiate and understand the data-space.

Hypermediated Hyperthoughts

The other aspect of Archive Dreaming that sets is apart from a simple digital database is the flexibility that it provides users. The system allows visitors to browse all 1.7 million documents in the archive in a variety of modes. Each mode draws different associations between the documents in the archives, assisting viewers to form relationships in a way that is suitable for their individual needs. In this way, the installation “intertwines history with the contemporary, and challenges [the] immutable concept of the archive.” This changing perception of the relationship between documents will seem familiar to those that have read the works of Vannevar Bush.

When Bush penned his ideas for the Memex in his essay As We May Think, he was operating in an environment that was vastly different to ours today. While he lamented that the traditional index based referencing was counter-intuitive to how we approached thinking, the recent data explosion has made it all but impossible for even hypermedia to serve as a viable solution. Sifting-through and organizing data is now a task best left to algorithms and machine intelligence. Standing in for human curators, these systems are capable of independently creating associations and forming relationships between countless datasets. These machines operate as we may think, but at speeds much faster than humans.

This realization is not lost on Refik Anadol either. In this post-hypermedia age, Archive Dreaming utilizes Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence to look at, understand and organize all of the content found within SALT’s large set of documents. The system builds its own set of definitions and correlations to make sense of the data, autonomously without human intervention. This codified information is then easily controlled by visitors from a touch sensitive console at the center of the installation space.

This interface showcases the benefit of digitizing the analogue experience of accessing a library’s collection. Users are able to much more easily access the content, with the process made more tactile and immediate. This also has the benefit of externalizing human intelligence, allowing us to transcend the limitations of what we can achieve with our own minds. In this regard, one begins to question if the gesamtkunstwerk of the future should also concern itself with the processing of data, in addition to using it as its medium.

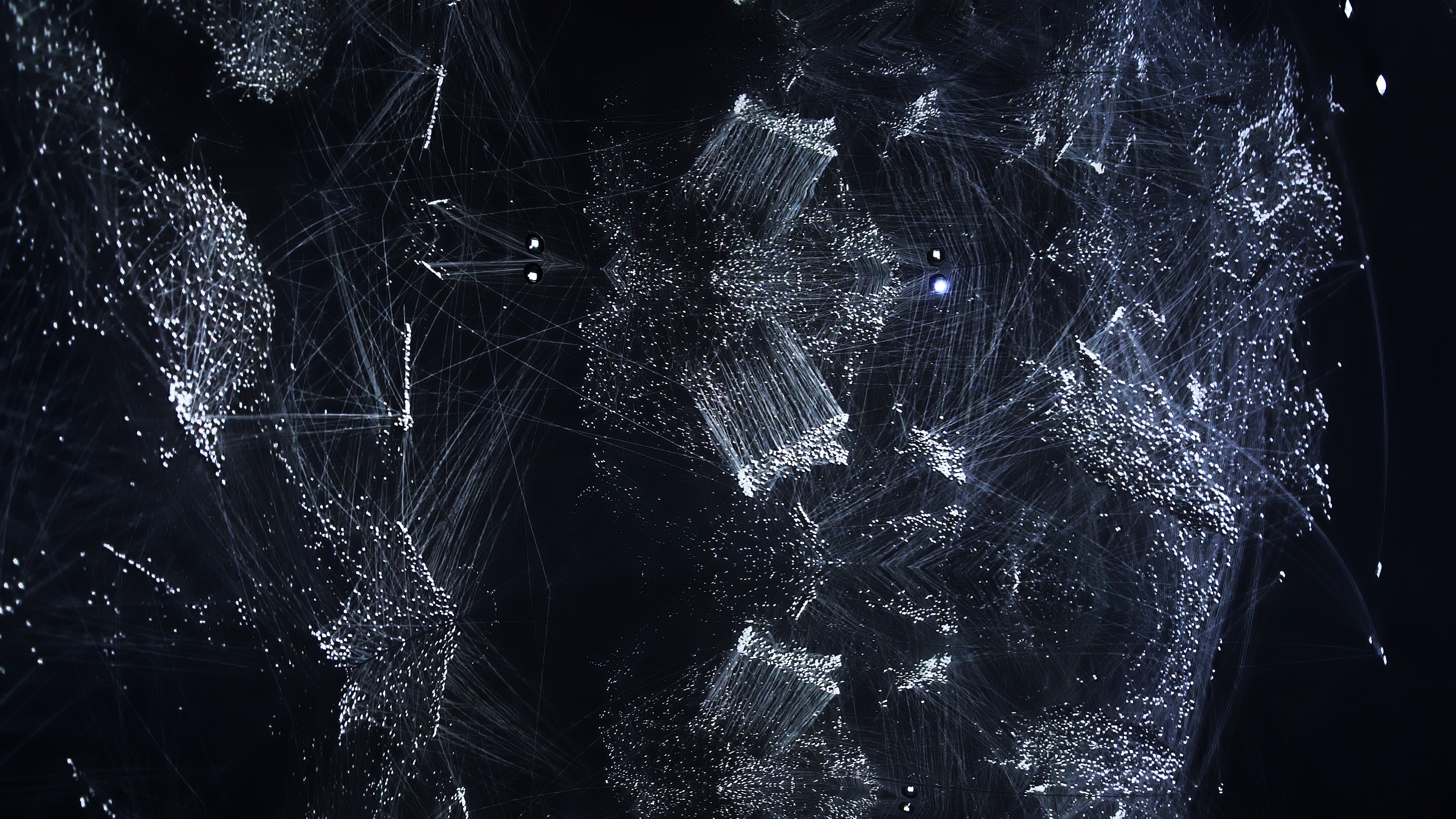

Data Dreaming

While Machine Intelligence has proven to be useful in helping humans circumvent the limitations of our intellectual minds, it also holds great potential in augmenting our creative minds. In Archive Dreaming, machine intelligence takes center-stage for the final aspect of the installation. Getting its name from this process, the installation enters into a “dream mode” when no one is interacting with it. The system uses the knowledge gained from studying and classifying all of the 1.7 million documents to “hallucinate” new ones that could possibly exist in the archives. Although the results may sometimes appear fuzzy and underdeveloped, acknowledging that humans are no longer the only ones capable of creative execution is a sobering thought.

The dreaming feature of the installation is powered by the emerging field of Generative Adversarial Networks. This technology allows computers within the system to learn and evolve completely unsupervised. This presents new challenges for creatives working with technology both as a medium and as a subject matter. Now that machines are capable developing their own sense of aesthetics, how do we as creatives navigate this new space in art-making? In the case of Refik Anadol, he has chosen to embrace this development to work in concert with the machines, furthering his study and practice of media art. One could postulate then, that the future of media art is shifting towards the eventual removal of the human from the creative process entirely and that Anadol’s works are the first steps in this direction.

Perhaps the future of the gesamtkunstwerk lies in the complete release of creative control, allowing machines to determine the optimal experience required for a total artwork. Perhaps the role of the human artist in the future would be to provide vague suggestions while the machine computed the final visual outcome; creating as they the machines might think, as opposed to how we think.

Conclusion

In 1966, engineer and friend of artists Billy Klüver gave a talk about the changing relationship between art and technology. In it, he mentioned that up until that moment, art had remained “a passive viewer of technology.” However, more and more creatives had begun to experiment with the inclusion of technology, challenging and redefining what art meant. Despite this progress, to Klüver, an engineer was only “raw material for the artist” the same way paint and charcoal would have been. This seemed to suggest that while important cross-pollination was happening, art and technology were still very much divided into their own camps, and a true blend of both disciplines had yet to happen.

But as Klüver so rightly pointed out, for Aristotle “Techne” meant both art and technology. And indeed, they should exist as the same thing. We have come a long way since Wagner’s first foray into actualizing the gesamtkunstwerk. Art and technology are now so deeply intertwined, each informing the other and erasing the hard boundaries that were still present slightly less than 60 years ago. The future of media art is dependent on this continued partnership. It is important for man to continue pushing the boundaries of the artistic practice, be it through the embrace of technology, or the resistance of it. The total artwork then, becomes a futile pursuit, forever changing as the technology available to us evolves. Maybe the pursuit should instead be of something grander and more ambiguous — a pursuit of honesty and artistic purity, choosing to create works on a medium that best represents the views and intentions of the creative.