“You may not be physically stronger, but you can show strength with your words.”

In the article written by Nicole Kelner, she talked about her rape experience and the importance of saying no. We have learnt in class the importance of consensual sex and the discursive construction of consent. We learnt that in opposite-sex assaults, in particular male-on-female rapes, it is insufficient to reject sexual advances or assaults with only body language, but one must explicitly say ‘no’.

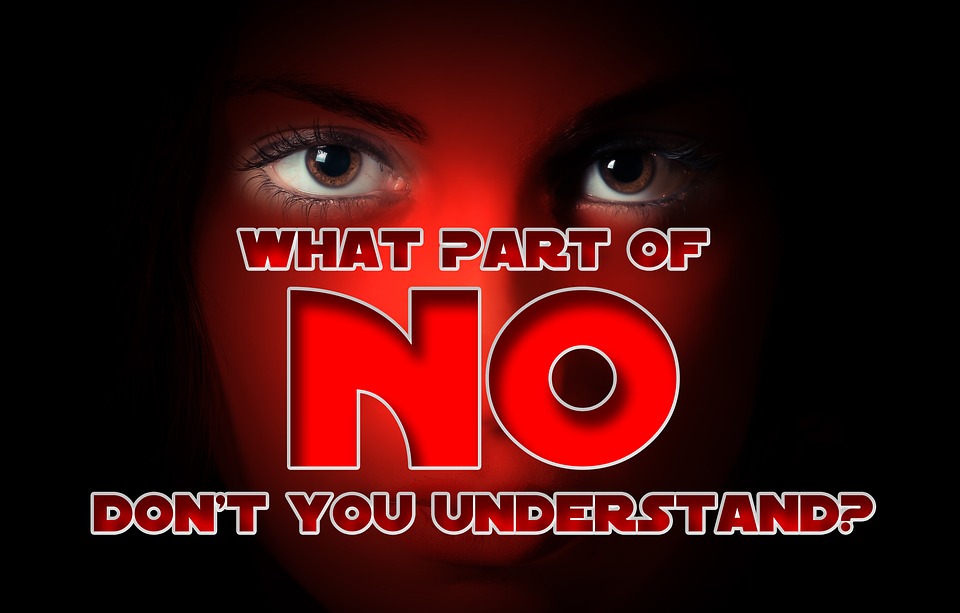

Kelner made an interesting point in her article: not only does saying no matter, the words you use to say ‘no’ matters even more. Instead of only saying ‘no’ (which did not stop her assailant) or ‘I do not want to have sex’, she thought she should have explicitly said that he was raping her. And if he had continued, she should have said with more affirmation that she will report him to the police for rape. Why is saying ‘no’ not enough to stop a rape from occurring? The word ‘no’ itself poses a conundrum. It is (in some men’s heads) translated to: saying no is a facade, internally she is screaming yes. She is just acting coy, ‘playing hard to get’, or arguably trying to come across as innocent and not wanting to seem like a nymphomaniac. ‘No’ to many still means ‘yes’ and thus consent. The problem with rape and consent discourse is that it rarely ever is the assailant who has to ask for permission – the assailant is given the power to discern from the victim’s words, facial and body language whether it is consent or not. Even if the assailant assumed wrongly, the blame is in most cases still put upon the victim for using the wrong choices of words or for giving mixed signals.

Out of curiosity, I searched intensely on how most victims said no to sexual advances, both verbally and non-verbally and unsurprisingly, female victims use more non-verbal cues. In particular, I was interested in same-sex assaults. What happens during same-sex assaults? Why is rejection not enough to stop same-sex rapes from occurring too?

Some argue that it is because men are expected to have an insatiable sex appetite, and therefore always welcome sex. But is that the case for male-on-male rape? Male victims still say no and fight back physically, yet they are often mistaken by their assailants that they are enjoying it because of their erections (Fuchs, 2004). Uncontrollable bodily reactions speak more to the attacker than actual rejection, does it really work if sex education teaches you to say no anyway?

Female-on-female rape cases are even more puzzling. Women do not react physically (in terms of orgasms) like men do. Yet 44% of lesbians and 61% of bisexual women have been raped, compared to 35% of heterosexual women. The fact remains that saying no does not work. The fact remains that saying yes to mean consent and saying no to mean rape is all but an ideology. Like the author said, saying ‘no’ is just insufficient.

Sex education teaches us to say no. Parents remind us to say no. People on the net tell others to just say no firmly. But rapists, in heterosexual and homosexual assaults, simply do not relate ‘no’ to rape. When constant ‘no’s do not work, exactly what words spoken can stop a rape from happening?

What is the point of saying no when it does not work? There has been few studies about opposite-sex assaults and the discursive construction of consent, much less on same-sex sexual assaults. What should one say to protect themselves from rape? Since there is grammar and syntax for one to learn what sexual arousal looks and sounds like (Beres et al., 2004)… perhaps, as ridiculous as it sounds, one day there will be grammar and syntax other than saying ‘no’ to protect one from rape.

References

Beres, M. A., Herold, E., & Maitland, S. B. (2004). Sexual Consent Behaviors in Same-Sex Relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(5), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000037428.41757.10

Fuchs, S. F. (2004). Male Sexual Assault: Issues of Arousal and Consent. Cleveland State Law Review, 51(1), 93–122. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2007.54.1.23.