What senses you are manipulating and how does this change your sense of emotion or feeling in space?

When we think of manipulating sight we usually think of the extreme and taking sight away completely. Yet for many of us, the intermediate steps of blurr y vision are lived realities that our youth and corrective lenses help us forget. While blurry vision may not evoke the same sense of panic and disorientation while blind, they still bring intense discomfort and frustration especially for long periods of time. We take (clear) vision for granted.

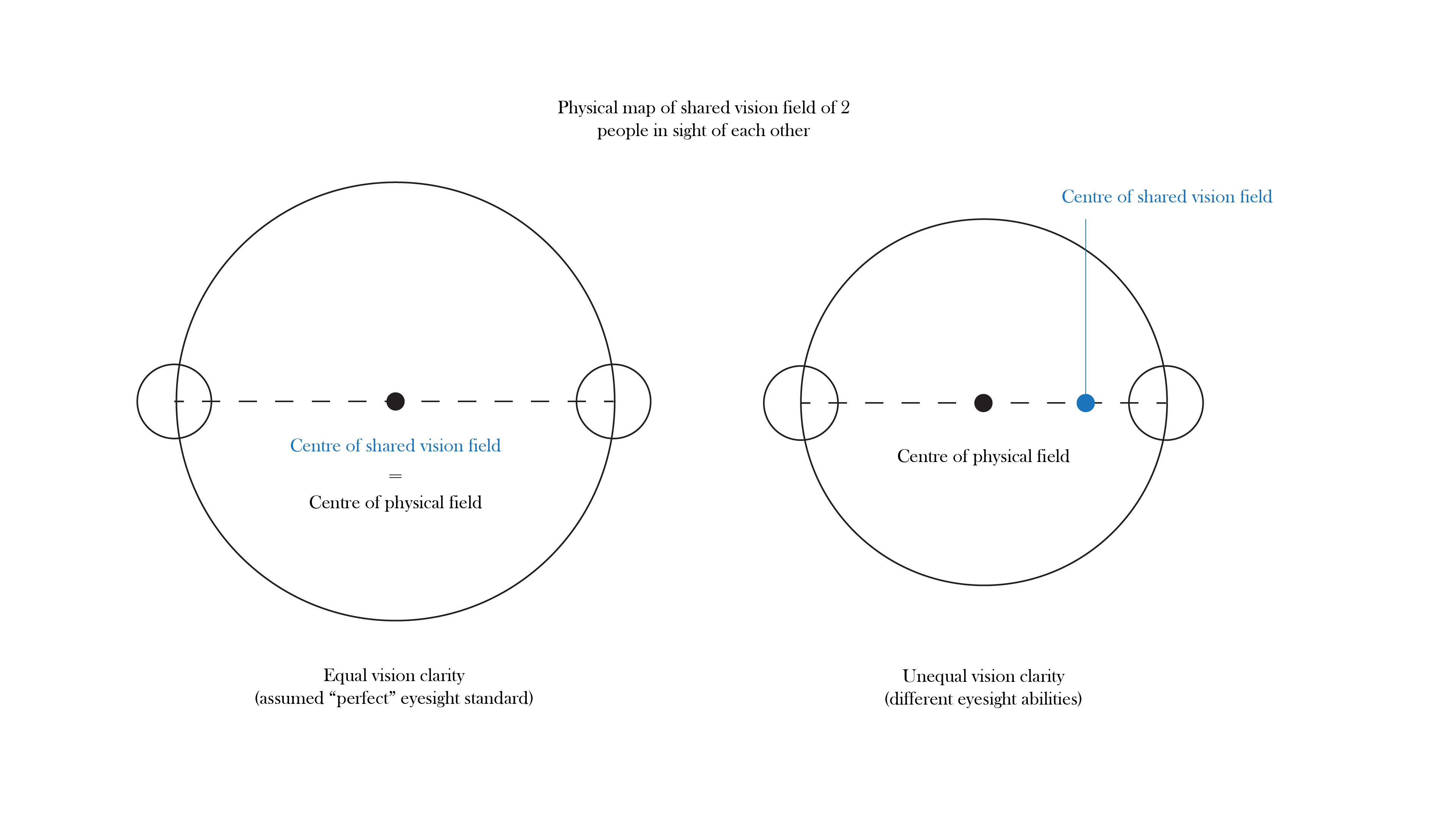

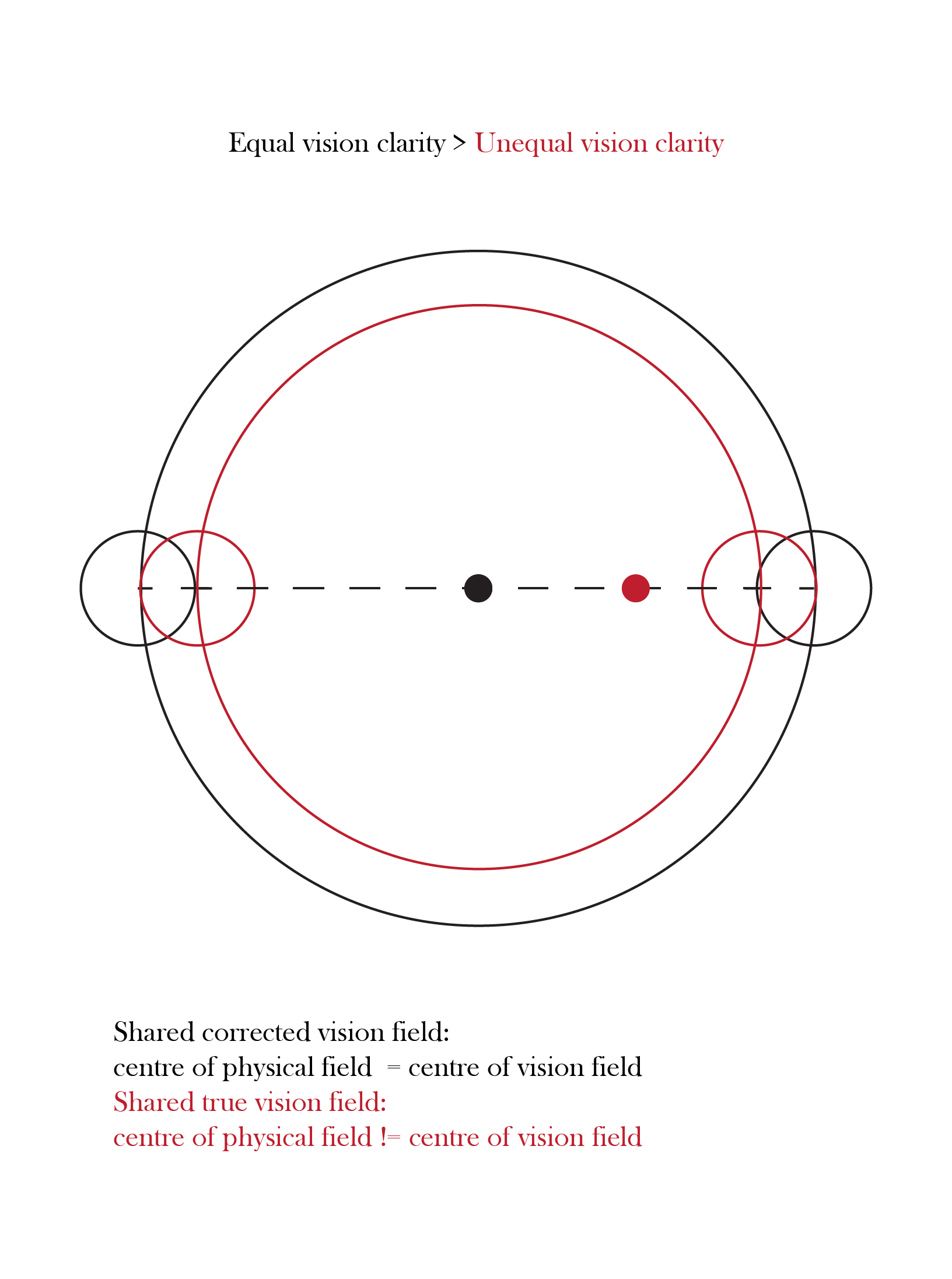

The mapped circle around two myopic people is smaller than that of two with “perfect vision”. While physical proximity does not translate to relational intimacy, I’d like to think that people are closer together when they occupy a shared field of their true vision; they are further sensitised to the differences in their eyesight and the need to communicate and accommodate each other to remain in each other’s field of vision.

The person with better eyesight has the benefit of greater comfort and security in the space drawn about the pair. As this person, I felt a sense of responsibility towards Yi Xue, and some discomfort in knowing we were unequal in this circle meant to enclose our shared field of vision.

To share/make a space with another, awareness of the differences between two people is required – and by extension, accommodation from at least one of them. Dejan also raised a point about honesty being needed for the circle to be drawn true to its intention; mutual trust is also necessary. It was suggested that eyesight test cards could be used to verify positions of the two people at a certain distance to map more accurate distances, but even this in hindsight requires trust from both parties to respond honestly to the test cards.