A Companion to Digital Art is a collection of essays, edited by Christiane Paul that gives a good introduction to the definition and characteristics of digital art. The essays explore the histories, aesthetics, politics, and social context of digital art, as well as its relationship to institutions and its historicization, in terms of its presentation, collection and preservation.

In the section on the politics of digital art, it is covered how the “technological history of digital art is inextricably linked to the military‐industrial complex and research centers”. For some reason, this darker history of digital technologies makes me appreciate digital arts even more. Digital technologies were developed and advanced within a military context, as weapons to serve destruction and create discord between people. Digital artists take the same technologies and envision them to be used creatively for utopian ideals, to create positive social and political change to benefit mankind. Digital art is an attempt almost, to salvage the mistakes of mankind and restore faith in humanity. It comforts me to know this, as much as I am conscious of the risk of these technologies being misused and creating a dystopian climate of distrust nonetheless – unsurprisingly, this is an issue contemporary digital arts frequently address.

___

Paul defines digital art as “digital‐born, computable art that is created, stored, and distributed via digital technologies and uses the features of these technologies as a medium.” Before, I hadn’t given much thought to the definition of digital art or new media, much less the necessity of assigning one at all. I held the reductionist view that whatever contemporary art (I had mistakenly equated ‘contemporary’ with ‘new’) that employed technology, and perhaps with mixed media, qualified as “new media” or “digital art”. However, given the ubiquitous use of digital technologies in even traditional art forms today – in photograph, print, sculpture and painting even – I have re-examined my position after learning about the inherent characteristics unique to the digital medium that, employed as a tool for creation, rather than production, make a work digital art.

Of these intrinsic characteristics, Paul highlights that digital art is computational; process‐oriented, time‐based, dynamic, and real time; participatory, collaborative, and performative; modular, variable, generative, and customizable, among other things. The characteristics of digital art that pertain to time and change intrigue me the most.

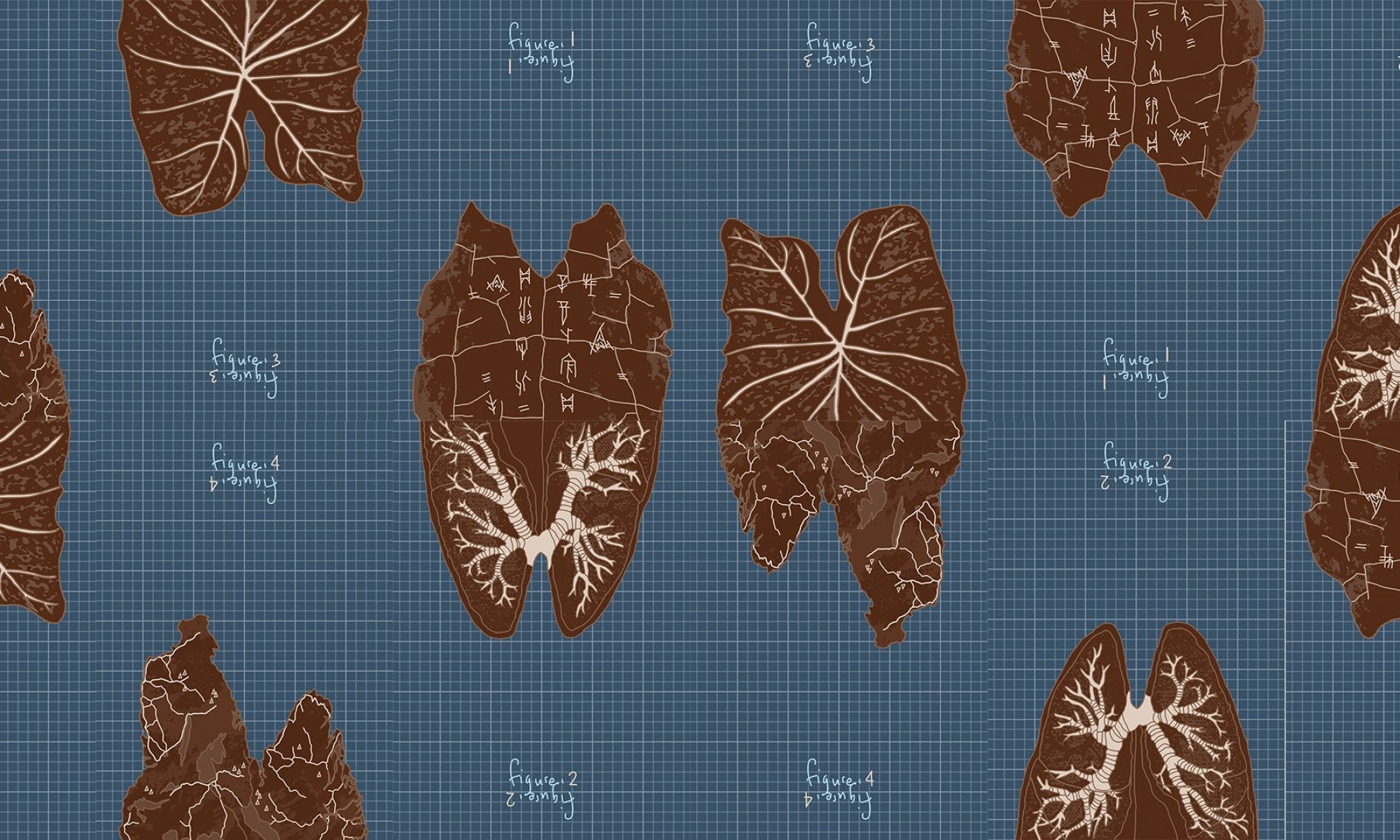

D N A Y I M C DIGITAL ART

DYNAMIC: DEFINITION

With the continuously changing state of the digital medium and its methods of application, it is perhaps unsurprising that the terminology and definition for technological art forms has always been extremely fluid too. What is now known as digital art has undergone several name changes since it first emerged: originally referred to as computer art, then multimedia art and cyberarts (1960s–1990s), art forms using digital technologies became digital art or so‐called new media art at the end of the 20th century.

DYNAMIC: MEDIUM

With the medium of technology I think it is interesting that new media’s characteristic of being “dynamic” and “time-based”, evolving and advancing with time, is not limited to the understanding of the nature of a single artwork, but extended to the entire medium as well. The medium of technology itself is always changing, we hear the words “technology” and “advancement” go together all the time. This is in contrast with other traditional mediums like painting and sculpture which are not “dynamic” in relation to time. The medium itself does not continuously change and take on a different form as drastically as technology does, because the traditional materials themselves are derived from nature, while technology on the other hand is literally immaterial software “generated out of thin air”. Changes within traditional mediums involve technologies changing the way materials are manipulated and used, less so involving changes in the nature and form of the materials themselves. Time-based dynamism in media form is a characteristic unique to new media art.

DYNAMIC: PRESERVATION

“digital artworks seldom are static objects but evolve over time, are presented in very different ways over the years, and adapt to changing technological environments.”

I find it interesting that the “posterity” and preservation of digital art differs so much from those of traditional art. While preservation of traditional paintings is concerned with protecting the original state of the work and exhibiting them in their unchanging static state – or with time-based mediums, exhibiting the work as it registers changes from the flow of time – this is not necessarily so for digital art.

“The variability and modularity of new media works implies that there usually are various possible presentation scenarios: artworks are often reconfigured for the specific space and presented in very different ways from venue to venue.”

It is easy to assume that the immateriality of technologies allows the original state of a digital artwork to be preserved for generations after easily. However, digital art is engaged in a continuous struggle with an accelerating technological obsolescence that serves the profit‐generating strategies of the tech industry. This obsolescence contrasts with the illusion of advancement with time, when one thinks of “technological advancement“. Unlike traditional media like paint, technology is less subjected to material changes like crackling with the flow of time. The changes that transform digital art from their original state (those that do not continuously reconfigure themselves over time) are instead advancements in technology driven by humans, changing not the form but the context within which digital art is displayed. This presents institutions with difficulties in the preservation of digital art.

“Probably more than any other medium of art, the digital is embedded in various layers of commercial systems and technological industry that continuously define standards for the materialities of any kind of hardware components.”

DYNAMIC??? CONTENT

One of my favourite insights I gained about digital art is how how the rapid change and advancement of the medium itself does not imply or necessitate likewise for the content and ideas behind new media works. It is true that many new media artworks explore issues that are current and pertinent to our time – especially those central to the conditions of the age of technology we live in, since the very medium makes it effective to do so. However, it is also possible for the concepts explored to date centuries back, addressed previously in various other traditional arts. Digital artists continue to address universal and timeless human concerns, with new technologies.

Not everything about digital art is necessarily new and dynamic afterall.