The essay explores space as a humanly construed concept, beyond the conventional understanding of space as a mere physical atmosphere or environment. It takes an anthropocentric view in explaining how people organise space differently – and similarly – with respect to their own living bodies. I appreciated how the essay drew a web of connections between different bodies (biological, cultural, social) and relations (people-people, people-space, people-time etc.) based on space.

One thing that stood out for me was the primacy of vision in defining the living body’s experience of space and the spatial schema imposed on it by extension. To perceive and measure space in terms of height and proximity relations etc., sight plays a crucial role. It would be interesting however to explore how the schema and vocabularies of spatial organisation might be different, if man relied on non-visual stimuli and experiences from engaging other senses instead. If we could not see, how would we divide, measure and assign value to space through only hearing, smelling and/or feeling the world? If we closed our eyes and were completely still (but awake, upright and conscious), and relied predominantly on our sense of hearing to engage with space, would right and left be primary, and front and back secondary instead? Since our ears are designed at the sides of our heads, the degree of sound stimuli from circumambient space would vary most along that axis. Might we also move along a horizontal axis, led by hearing instead – side-stepping like crabs in space instead of walking forward and backward “normally”? Proximity relations might be informed by ambient sounds too, instead of distance and scale relations observed visually. While touch (and movement of our body to do this) might still allow us to identify the polarities and centres of a space without sight, how significant would these divisions be in influencing how we assign value to parts of a space? Where we still identify the centre and polarities of space based on touch alone, perhaps it is the ends of a space rather than its harder-to-pinpoint centre that gain greater importance for the sense of security and structure it offers a blind person. The position a blind person might value most might not be the centre of the world then but its ends.

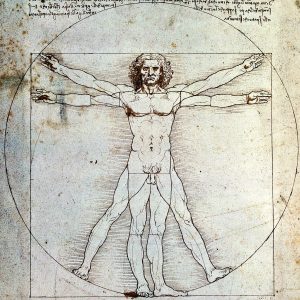

Space differs among different people because they measure and organise it with different bodies. But focusing on the living body as a “measuring tool” for space, space can also differ for the individual, if we augment the way we use our bodies to measure space.