Prof Jesvin invited Prof Ken Feinstein for a presentation on semiotics and discourse in two of the research methods class, where he talked about how establishing a discourse is important, and that meaning is defined by the discourse.

A language, such as visual language, is flexible and sometimes they do not even need to be real e.g. QWERTY. Discourses are empty vessels that want to be used, and they can be changed overtime or even be thrown away. For instance, alchemy used to be religious and widely practiced in different cultures, but it has since been superceded by science. So we can look at it in both ways: is the discourse changed (it became science)? or is it abandoned (science nullified it)?

Discourses evolve and they change along with the conditions. How we understand something gets altered overtimed due to the circumstances. It is up to us to understand how something can apply in the real world. For example, data visualisation can be said to be a fusion of science and visual communication, and you need to find something that is meaningful to convey to your target audience. To geologists, the facts matter more. To artists, it will likely be aesthetics over factual information. It all depends on who you are targetting at, and create the meaning accordingly.

For your FYP: what is the meaning that you are trying to create?

Semiotics: A Primer for Designers by Challis Hodge

- Semiotics can be described as the study of signs.

- Not signs as we normally think of signs, but signs in a much broader context that includes anything capable of standing for or representing a separate meaning.

- “Semiotics tells us things we already know in a language we will never understand.”

- semiotics is important for designers as it allows us to understand the relationships between signs, what they stand for, and the people who must interpret them — the people we design for.

- Understanding Design as a Dialogue:

- Semiotics teaches us as designers that our work has no meaning outside the complex set of factors that define it.

- These factors are not static, but rather constantly changing because we are changing and creating them.

- It helps us to understand that reality depends not only on the intentions we put into our work but also the interpretation of the people who experience our work.

- Meaning is not contained in the world or in books, computers or audio-visual media. It is not simply transmitted—it is actively created, according to a complex interplay of systems and rules of which we are normally unaware.

- Sign:

- Symbol: Stands in place of an object – flags, the crucifix, bathroom door signs.

- Index: Points to something – an indicator, such as words like “big” and arrows.

- Icon: A representation of an object that produces a mental image of the object represented. For example, a picture of a tree evokes the same mental image regardless of language. The picture of a tree conjures up “tree” in the brain.

- Signifier:

- Is in some ways a substitute or stand-in. Words, both oral and written, are signifiers. The brain then exchanges the signifier for a working definition.

- The word “tree,” for example, is a signifier. You can’t make a log cabin out of the word “tree.” You could, however, make a log cabin out of what the brain substitutes for the input “tree” which would be some type of signified.

- Signified: What the signifier refers to

- Connotative: Points to the signified but has a deeper meaning. An example provided by Barthes is “Tree” = luxuriant green, shady, etc.

- Denotative: What the signified actually is, quite like a definition, but in brain language.

- Discourse: Messages that serve a communicative function and are usually more complex than simple signs.

- Coding: The process of choosing images and placing them in a context that will convey your intended meaning

References:

http://boxesandarrows.com/semiotics-a-primer-for-designers/

http://www.creativebloq.com/computer-arts/semiotics-beginners-3059924

—

My understanding from the above reading is that all these visuals don’t have any meaning until we assign one to them. Stuck at a roadblock in my (tragic) attempt to create content for my project, I found that a good example for me to learn from is an anime that my peers suggested after knowing that I’m researching on alchemy—Fullmetal Alchemist.

Hiromu Arakawa, creator of the original manga, became attracted to the idea of having characters use alchemy after reading up about the philosopher’s stone. Besides using alchemy’s philosophical concepts, she also infused the series with her own beliefs such as ‘The Law of Equivalent Exchange’ inspired by her parents who worked hard in a farm to earn a living.

She also wanted to integrate social issues into the story, so research involved watching television news programs and talking to refugees, war veterans and former yakuza. Several plot elements, such as Pinako Rockbell, a neighbour and grandmother, caring for the two main characters, the Elric brothers, after their mother dies, and the brothers helping people to understand the meaning of family, expand on these themes.

Although alchemy declined in practice when the Industrial Revolution was happening, Arakawa was amazed by differences in the culture, architecture, and clothes of the era and those of her own culture, hence setting the time period of the story in this period.

There are many ways that Arakawa has used her research on the philosophy and symbols of alchemy and made it into something that’s her own, but I am going to zone in on a few that have caught my eye:

1. 7 Deadly Sins / Homunculi and the Ouroboros Tattoo

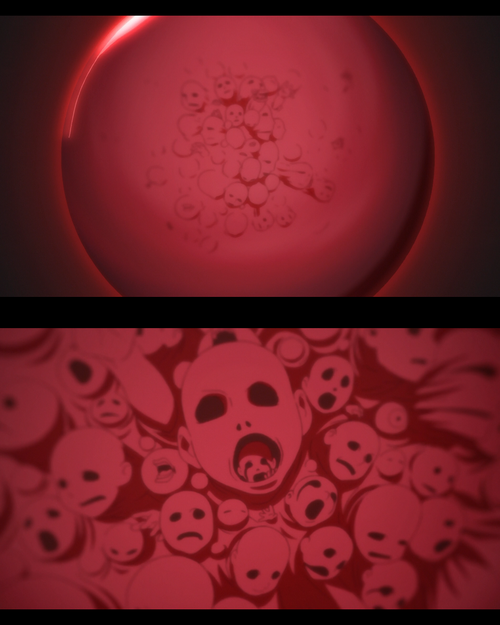

The 7 deadly sins are artificially created humans called homunculi. In the context of ‘real-life alchemy’, a homunculus is a representation of a small human being, often referred to the creation of a miniature, fully-formed human. Currently, in scientific fields, a homunculus may refer to any scale model of the human body that illustrates physiological, psychological, or other abstract human characteristics or functions.

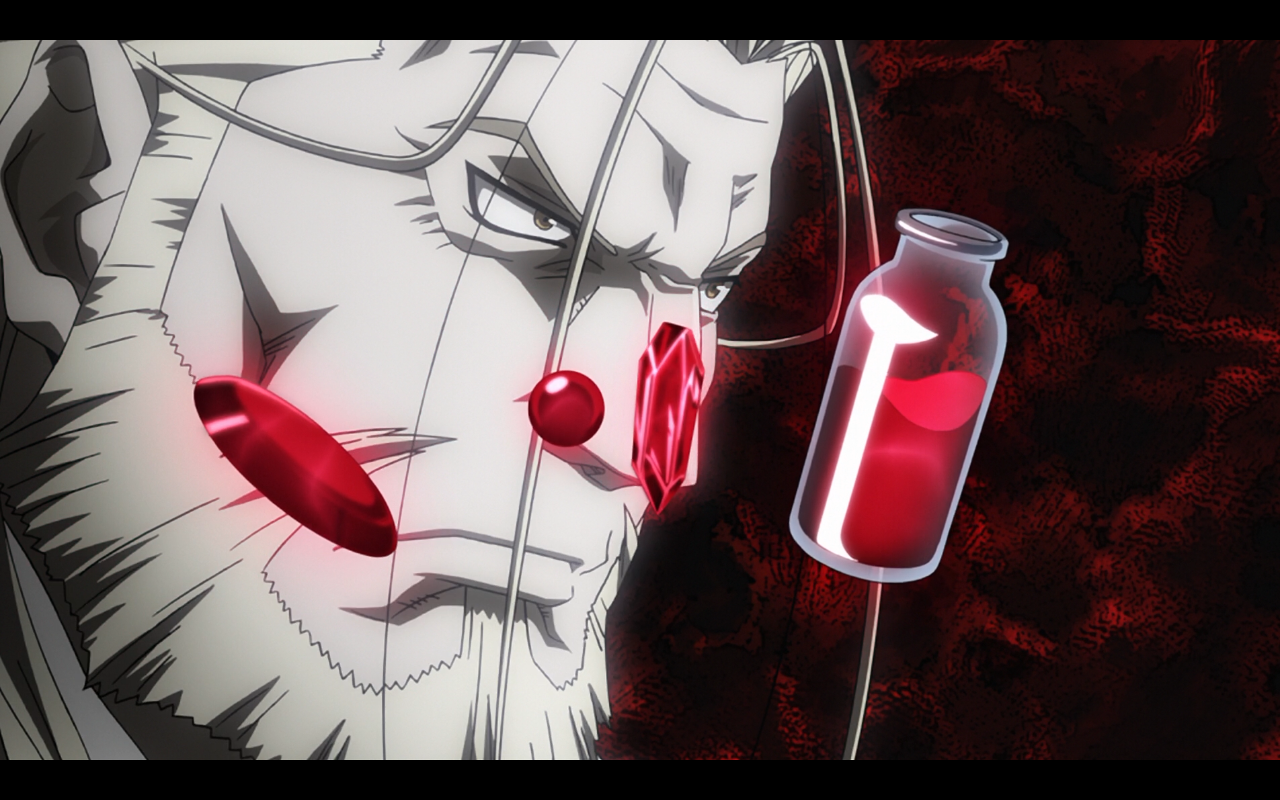

On the left is the ancient visual representation of a homunculus; on the right is Arakawa’s rendition. The only visible similarity is the fact that both are contained in a vessel, but the way in which the homunculus is being depicted is clearly different.

Arakawa made it such that if the formless homunculus escapes from the flask, it is able to inhabit a ‘human-like’ vessel, but can shape-shift back to its original form as and when it likes.

Each homunculus has an Ouroboros tattoo on a specific body part, e.g. Gluttony’s is on its tongue, Lust’s is on its sternum above her chest, and Greed’s is on its hand (below).

Here’s where Prof Feinstein’s presentation on discourse made sense to me: in this anime, one would mainly recognise an Ouroboros tattoo as “the mark of a homunculus”, but in the context of ‘real-life alchemy’ as well as many religious or cultural symbolism, an ouroboros symbolises self-reflexivity or cyclicality, especially in the sense of something constantly re-creating itself, rebirth, or the eternal return; “all is one, and one is all”. It could also be interpreted as the Western equivalent of the Taoist Yin-Yang symbol.

Hence, due to the discourse established by Arakawa, the meaning of the ouroboros is changed, even though she does retain certain ‘truths’ such as the homunculi’s ability of regeneration.

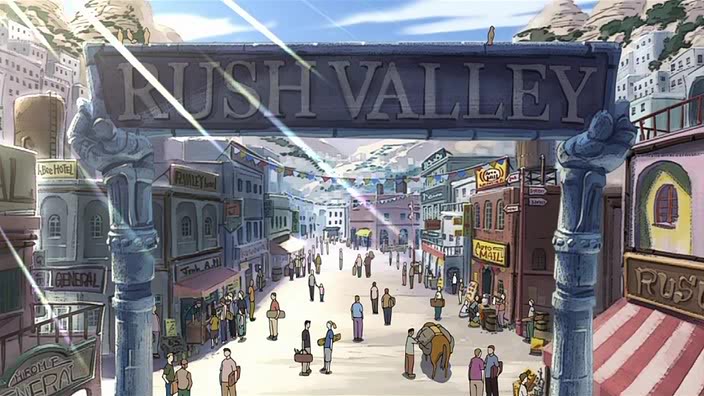

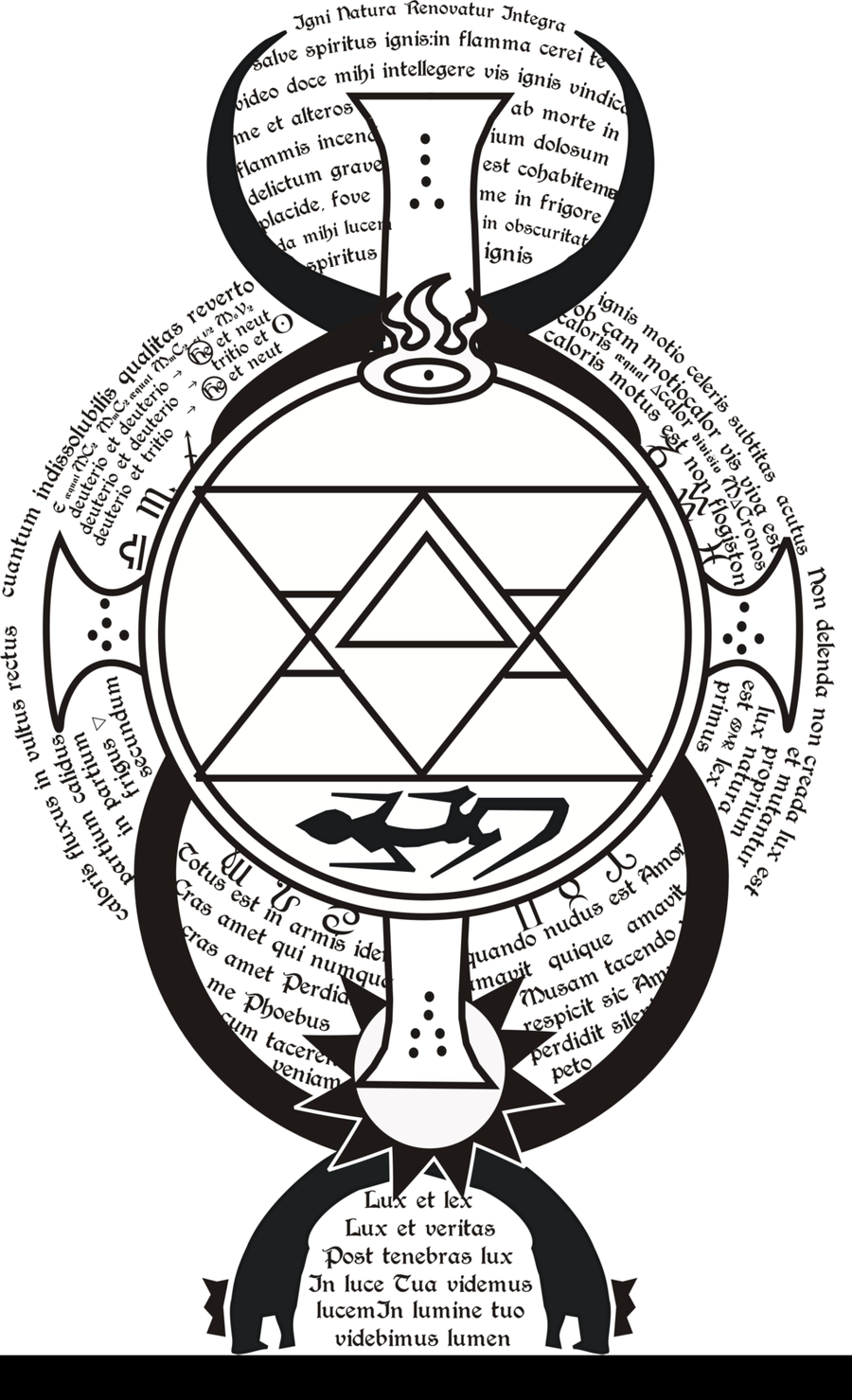

2. Transmutation Circles

Traditionally, alchemy is done through laboratory processes, but in the anime the characters could do so through something entirely original of Arakawa’s called transmutation circles.

The circle itself is a conduit which focuses and dictates the flow of power, tapping into the energies that already exist within the earth and matter. It represents the cyclical flow of the world’s energies and phenomena and turns that power to manipulable ends.

Inside the circle are specific alchemical runes. These runes vary widely based on ancient alchemical studies, texts and experimentation, but correspond to a different form of energy, allowing the energy that is focused within the circle to be released in the way most conducive to the alchemist’s desired effect. In basic alchemy, these runes will often take the form of triangles (which, when positioned differently, can represent the elements of either water, earth, fire or air), but will often be composed of varying polygons built from different triangles.

The 2 examples below show ‘fire transmutation’ symbolism.

As mentioned earlier, Arakawa also made her belief on having equal input and output central to the whole alchemical process in this anime—Equivalent Exchange: “In order to obtain or create something, something of equal value must be lost or destroyed.”

The mystical practice of alchemy to create objects out of raw matter or turn one object into another is widely believed to be capable of anything, and it is often viewed as magical or miraculous by those characters who are unfamiliar with the craft—but it is a science and as such is subject to certain laws and limitations.

3. Philosopher’s Stone and Flamel’s Cross

The philosophers’ stone is created by the alchemical method known as The Magnum Opus or The Great Work. Often expressed as a series of color changes or chemical processes, the instructions for creating the philosophers’ stone are varied. When expressed in colors, the work may pass through phases of nigredo, albedo, citrinitas, and rubedo. When expressed as a series of chemical processes it often includes seven or twelve stages concluding in multiplication, and projection.

The ingredients of the stone vary from source to source, but to drive the moral part of the plot, Arakawa made it such that human lives are key ingredients for it. Moreover, philosopher’s stone are seen to be the ultimate goal in alchemy, whereas in Fullmetal Alchemist, the stone is a tool to either make the characters more powerful, or as an ingredient for a transmutation process.

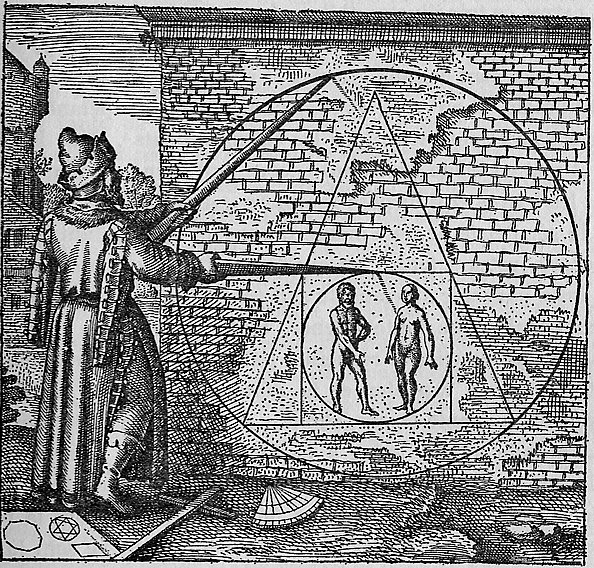

It seems also that the visual depiction of the Philosopher’s Stone vary too, with some illustrating the process and some illustrating it through geometrically-driven metaphors like the ones below. In the early texts, literal depiction of the Philosopher’s Stone as an actual stone is rare unlike in contemporary literature e.g. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

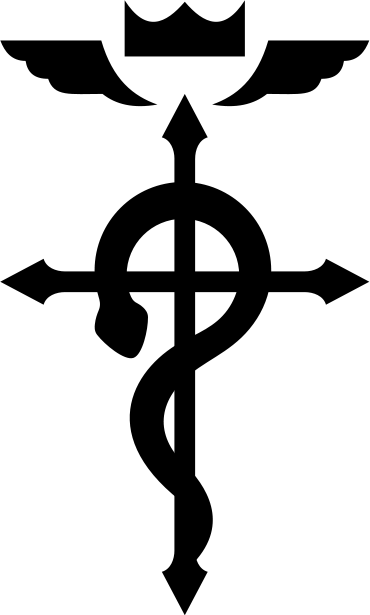

Nicolas Flamel developed a reputation as an alchemist believed to have discovered the Philosopher’s Stone and achieved immortality after his death. He has since appeared as a legendary alchemist in various fictional works. When he died, he left some symbols to adorn his grave, one of them being Flamel’s Cross, and many say that this was to symbolise his relation to the stone.

It actually refers to creating a philosophers stone by “crucifying a serpent.” It’s a metaphor for purifying something that is venomous, or dangerous, and becoming stronger with it. What it also consists of, is the Rod of Asclepius. Asclepius was the son of Apollo, and he was the god of medicine and healing. This is why today, hospitals, insurance agencies, and other institutions relating to the health industry often make use of a symbol consisting of a snake entwined around a rod.

In Alchemy, the Flamel represents the “fixing of the volatile“, meaning stabilising the active principle, something which can separate harmful and beneficial elements from each other or even transform the harmful (pure active, too active) into the beneficial (balanced active). It is a vital step in the alchemical opus’ process, related to the making of the mercury’s elixir and of curative processes.

If we interpret snake = Mercury = spirit, which is a common symbol chain, then the symbol can suggest that the final “rendering” of the spirit, by death or enlightenment, will produce the pure, perfected, incorruptible spirit that, in alchemical terms, tends to go along with an incorruptible body. In this reading, the symbol indicates immortality, the standard promise of the philosopher’s stone.

Here, Arakawa modified the symbol a little by adding wings and a crown. As we can see in many manuscripts, wings are used to mark progress or advancement of an alchemical solution toward perfection. Crowns mark the final stage of a spirit or solution: perfection, completion, ascension.

Sources:

http://carljungdepthpsychology.blogspot.sg/2012/03/homunculus.html

http://www.tokenrock.com/explain-ouroboros-70.html

http://fma.wikia.com/wiki/Main_Page

http://anime.stackexchange.com/questions/3719/how-similar-is-alchemy-in-fma-to-the-real-alchemy

http://hubpages.com/hub/Fullmetal-Alchemist-Brotherhood-Religious-Symbolism-and-Discourse

http://www.levity.com/alchemy/flam_h0.html

http://members.ozemail.com.au/~clauspat/stonea.htm

https://carljungdepthpsychology.wordpress.com/2013/10/11/the-crucified-serpent-and-alchemy/

—

Professors Astrid, Louis-Philippe, Michael, and Nanci have all pointed out that I am very constrained by my research and am not putting my own interpretation into it. After watching the anime and analysing the way Arakawa has stayed true to her research but made it into something that’s hers, I have a better idea of how to go about developing content, meaning, and a ‘story’ for my project.