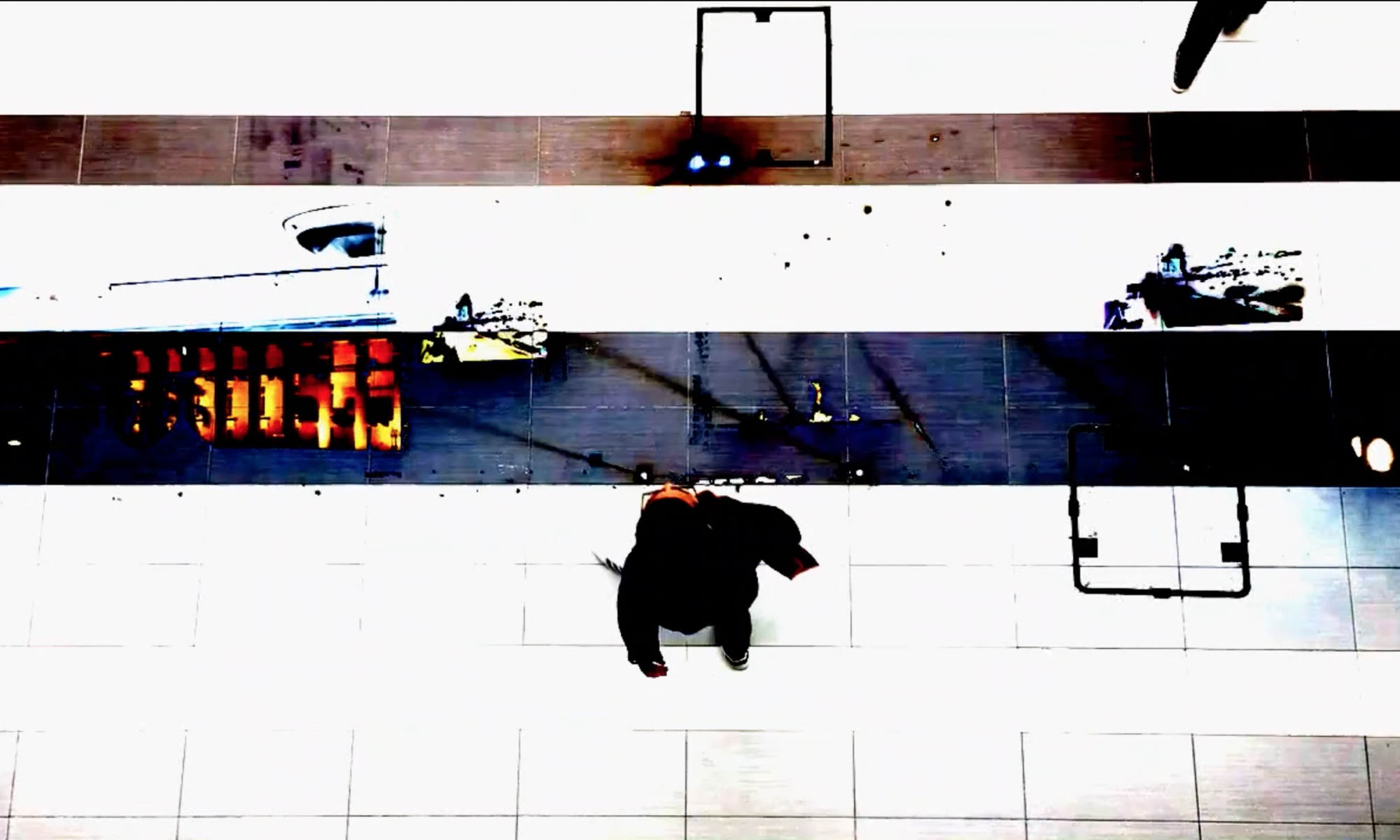

Aggregated audio and visuals from our daily lives can convey a new story through composition and technical distortion. The combined video and audio above speaks to the constant bustle of life in Singapore and the extravagant city life it appears to be as a leading Asian tourist and expat city. High color saturation and a variety of video movements figuratively represent the high energy of a sleepless and commercialized country. Noises blur together with bursts of sound from cars, overhead human voices, and a continuous muffled background noise that emanates from public spaces. Throughout the piece, people walking across the frame remains a constant so as to root the composition in how this visual and noise commotion affects the people whose lives it intersects.

Future World at ArtScience Museum Reflection

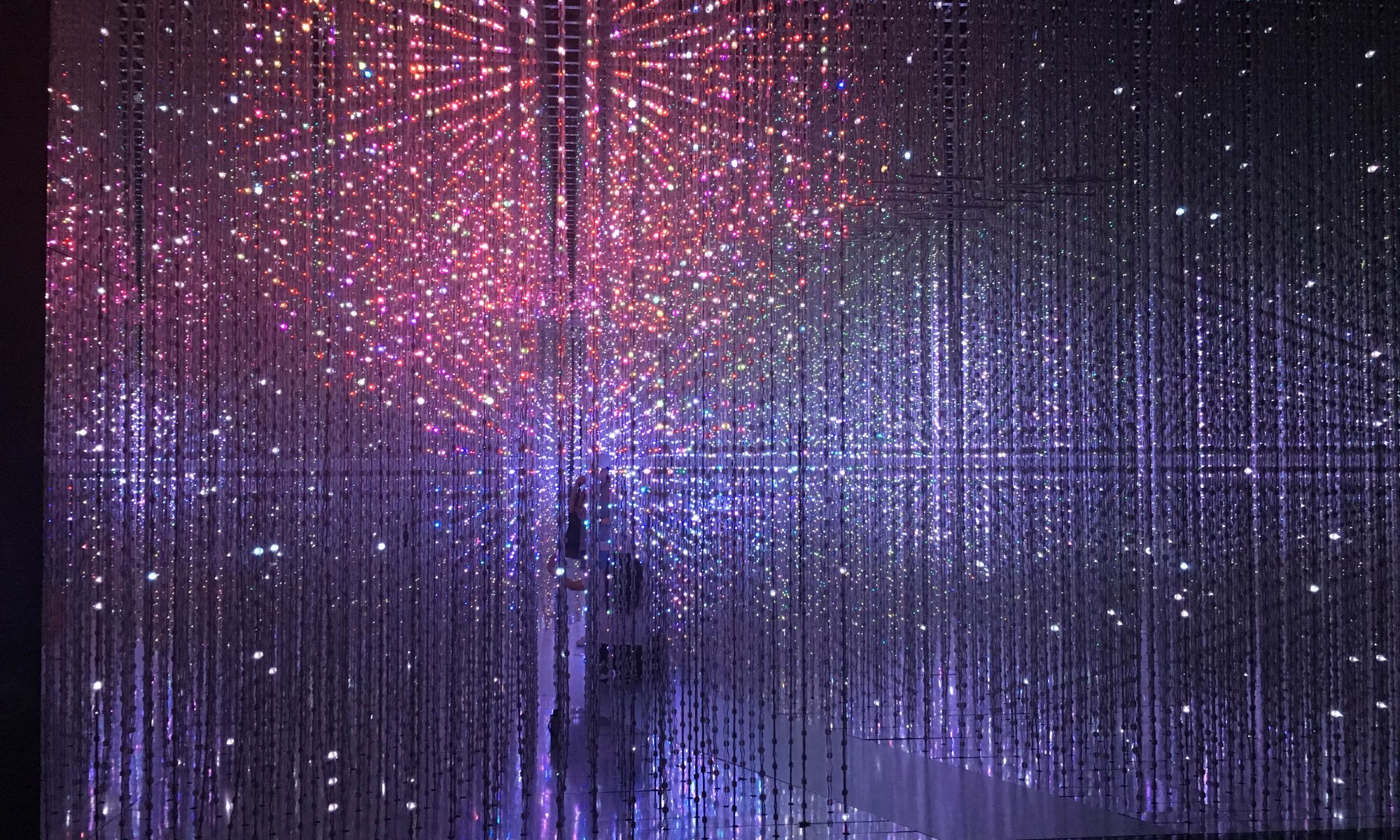

As a kid, we had yearly passes to the Cincinnati Children’s Museum where I had the most fun playing in the rain forest playground and walking through the ice age exhibit. These exhibits were educational immersive environments, just as many museum exhibits are designed to be. However, FutureWorld at the ArtScience Museum in Singapore uses technology and interactivity to add depth, exploration, and delight to the learning and fun that comes with visiting the museum. I felt I was a kid again as we colored in the lines and then saw our drawings dropped in a 3D moving city. And as we went down the slide three times to see the flower projections move beneath us. Every installation in the exhibit was interactive in a way that allowed people of any age to enjoy the experience.

The installation that I enjoyed most was Black Waves, a 3D rendered looping video of waves rising and falling across three large wall panels. Watching the waves move in a way that mimicked real clashing waves, as if they were alive, was unbelievably calming. Similar to many of the installations, it was such a simple idea. A room whose walls are waves moving up and down. Yet, the technical precision of the 3D rendering, the pace of the waves, the sound paired with the video, and the Japanese style (like Hokusai’s prints!) in which the art was created all contribute to one of the most peaceful exhibit installations I’ve ever been to. Choosing a simple and pinpointed idea and executing it with great technical skill and precision seems to be what made so many of the installations in FutureWorld memorable.

Takasu from TeamLab – the group that designed FutureLab – talked about the importance of prototypes when working on a multidisciplinary team. In the past two weeks, working with the IEM students, and even within our ADM group, the value of showing visuals to convey ideas is clear. Full prototypes would be preferred but sometimes time only allows sketches or inspiration imagery. Visuals make sure team members are picturing the same image in their head and prototypes add a level of real interaction that can then be tested. These understandings will definitely be implemented in how our group works on our iLight project this semester.

I feel like we are always trying to find some greater purpose in our art and design. But some of the times it is just a pretty picture and usually it is not going to “save the world”. But art CAN make people feel, think, play, smile, experiment, and learn. Future World is a great example of how impactful art can be when combined with science to allow playing and learning through technology.

Janet Cardiff’s Narrative Sound Installations

Janet Cardiff’s sound installations bring a new dimension to the sound pieces we have discussed so far: narrative. In her museum installations, her pieces each tell a story through the sounds she and her husband and collaborator George Bures Miller combine together with spoken language and visuals. Yet some of the most immersive of these narrative sound installations are the audio walks.

The first work I chose to listen to of Cardiff’s was actually a video walk, the Alter Bahnhof Video Walk. Properly named (Alter translates to “old” and Bahnhoff translates to “railway station”), this piece takes place in an old German train station in Kassel, Germany.

At the beginning of the video clip on Cardiff and Miller’s website, the audience is advised to wear headphones to hear the binaural audio of the video. Binaural audio results from a recording that uses two microphones, positioned to create a 3-D stereo sound experience for the listener. This surround sound enhances the immersive experience of watching and listening to Alter Bahnhof Video Walk and makes the viewer feel he or she is present in the space within the video.

This truly immersive experience is exactly what Cardiff was going for in her video walk both physically and digitally through the same train station. The audio recording is so believable that as I was listening to it with my earbuds I even questioned whether there was a dog barking outside by dorm room or if it was in the video. When I listen to loud music, I commonly take out my ear buds to see whether or not others can hear what I am hearing but this audio recording in the environment you are watching and standing in enhances the confusion of what is real and what is not by tenfold. On the project page of her website, Cardiff describes the piece as a “physical cinema” in which,

“An alternate world opens up where reality and fiction meld in a disturbing and uncanny way”

This uncanny nature of the video walk stems from the dual reality happening in front of you. Watching a video of a place in that exact place is not a typical experience, especially when aided by sounds that could exist in your present environment but do not. In the video, the narrator says “or lost somewhere in their mind” directly before the video flips to walking through a forest for a few seconds. While this randomly inserted video clip might seem obtrusive, it reminded me how it was more comfortable to watch a video displaying something that was different than my present environment. The narrator’s eerily calm voice adds to the disturbing atmosphere of the video walk as well, as if something terrible is about to happen any minute.

Many of these elements seem to be universal in Cardiff’s sound installations and part of her style. As I listened to Her Long Black Hair, there were many similarities between this audio walk through Central Park and the video walk through the German train station. Both have a strong narrative implication with an aura of mystery as Cardiff prompts you through a space with instructions on where to look and walk. In Her Long Black Hair, she takes the listener through a mystery in which there are some unsettling moments like discovering a crime scene. While listening, I felt I was listening to an audio book of a mystery novel with supporting pictures; yet, if I had been walking through the actual space I can only imagine how “real” the story would feel, as if it were a news story. It reminds me of the couple times I have had a book open while watching a movie version of the story, following along for a few minutes page by page. The description of the piece on Cardiff’s website describes the illusion of the experience accurately as,

“shifting between the present, the recent past, and the more distant past”

resulting from the listener’s environment, the narrator’s environment as she speaks, and the visuals in the photographs.

In a way, Cardiff’s style relates to the use of everyday sounds like Luigi Russolo or Bill Fontana; however, Cardiff’s works are much more contrived with narrative structure and purpose. Both pieces above speak about the affect of the past on the present and how we can blur time and space through what we hear and see. There is a bit of indeterminacy in the present surroundings of the viewer in the real environment as he or she goes through an audio or video walk. But primarily this juxtaposition of present and past scenarios in the same place is about the listener’s interaction with the narrative so that they feel they are an integral part of the performance. Essentially, the listener is engulfed in an immersive experience that they have no control over, despite being the main player in the story. Cardiff describes her work well, as an

“investigation of location, time, sound, and physicality.”

Sound: Bill Fontana and Acoustical Visions

Take a walk through nature and you can easily hear the musical noises of birds chirping or rustling trees. Many people have found their surroundings to be sources of harmonic noises, but Bill Fontana focuses on specific interactions within urban architecture in his sound art. For Fontana,

“the world at any given moment is a potential musical system.” (see below video)

Born in 1947 in Cleveland Ohio, Fontana is now an internationally known artist and composer of experimental sound sculptures.

Since his first sound sculpture in 1976, Fontana has elicited a connection between his audience and their urban environment by drawing out the living sounds of bridges, machinery, transportation, and structures in his acoustical visions. Wikipedia defines sounds sculptures to be art forms, commonly sculptures, that produce sounds, OR the reverse so that sound creates a sculpture. In a sense, the audio and visual elements of his explorations create each other, sound making an image and an image making sound. Sound is elevated to give audiences a new perspective of the visual environment in which the sculpture exists. Rudolf Frieling, the Media Arts Curator at SFMOMA since 2006, described these acoustical visions best, as…

“an audiovisual field recording, enhanced and abstracted in real time or in post-production [in which s]ound and visuals support each other[ and] no leading or supporting role can be identified in this interaction.”

In many of Fontana’s pieces he finds living sounds through everyday architecture or found spaces, inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s concept of ready-made objects. Of paradoxical nature, the installation Distant Trains reconstructs a historic train terminal in Berlin destroyed in the during World War II by projecting live sounds from another train station in the space. The space seems to create the sound just as the sounds creates a “new” space.

His piece Acoustical Visions of the Golden Gate Bridge channels the energy of cars and surrounding fog horn and boat sounds recorded from strategically placed sensors. Recorded sounds are heard from inaccessible vantage points and the live camera view is watched from a remote location to experience a situation in entirely new context with unpredictable audio and visual.

Watch Acoustical Visions of the Golden Gate Bridge here: https://www.nytimes.com/video/arts/design/100000001588737/bill-fontanas-acoustical-visions.html

My favorite art piece of Fontana’s is his 2006 piece Harmonic Bridge, a beautiful piece containing sounds from the inner workings of the Millennium Bridge in London. The bridge is alive through vibrations that result from the bridge’s dynamic movements caused by footsteps, wind, and cars. If I had been listening in person, I think I could have stayed in the Tate Modern gallery, where the living acoustic sculpture was exhibited, for a while. The sound was slightly recognizable with distinct moments sounding very much like a stringed instrument. The Tate Modern even describes the bridge as a vast stringed instrument as you listen throughout the space. Most importantly, the sculpture is captivating because the sounds come from a place humans are incapable of reaching without technology like the accelerators Fontana uses. Alan Riding of the NY Times puts the the piece into words perfectly:

“rising and falling, always different, at once strange and familiar, mysterious and evocative, hypnotic and sensual.”

As we start discussing contemporary sound artists, the connection to the forerunners in sound art is clear. Fontana strays from synchronization of his audio and visual elements just as Edgard Varese created infinite harmonic possibilities across unpredictable planes. To Fantana,

“the act of listening is a way of making music”,

reflecting the significance of silence and listening to our surroundings in John Cage’s work. I think that if after experiencing one of Fontana’s sound sculptures we leave with different perceptions of a certain urban space, then Fontana would be satisfied. Because ultimately, sound art is about creating a new experience that is only achievable with innovative technology and original methods of composing—whether Luigi Russolo’s noise machines, Varese’s organized sound, or Cage’s chance compositions. For Fontana, it happens to be his experimental placement of recording devices, the displacement of sound, and his fascination with “the found object” that supplies this new experience.

iLight Festival Installation Inspiration

Home

Simplicity in communication is one of the greatest qualities of a strong design. The light installation Home reconnects each person to their idea of home and memories. While such an elementary term, the meaning of home goes much deeper than the physical place we live in. Our home is commonly associated with our past, where we come from and the people, values, and memories that go with that place. People call all sorts of places home, whether a city, a house, a neighborhood, an apartment, a flat – wherever their greatest sense of comfort and care lies. The group of friends who designed this installation harkened back this basic definition of what a home is by deciding to replicate the most iconic image of a home, the four walled rectangular house with square windows, a single front door and peak sloped roof. The boundaries of the house feel present within the three-dimensional structure but the emptiness inside allows each person to imagine their personal home. Lack of extravagance in production of the piece add to its simplicity and immediate communication of a home. This light installation is a beautiful testament to the fondness of a home within a bustling concrete jungle.

Northern Lights

No matter how nice a city is, people are still enthralled with earth’s natural beauty. From great mountains to coral reefs the natural beauty of the planet is something we are drawn to. Artist Aleksandra Stratimirovic used this mesmerizing way about nature in her light installation Northern Lights. Strategically positioned above the bay, the LED light rods reflect vibrantly on the water below. Each viewer experiences the show slightly differently as the lights move around randomly, paired with a uniquely composed soundtrack for a more immersive experience. Northern Lights delights its audience because it brings a beautiful rare sight only visible in the far northern hemisphere to a tropical destination at the equator — an experience many do not see in their lifetime and just a hint of the full experience in nature.

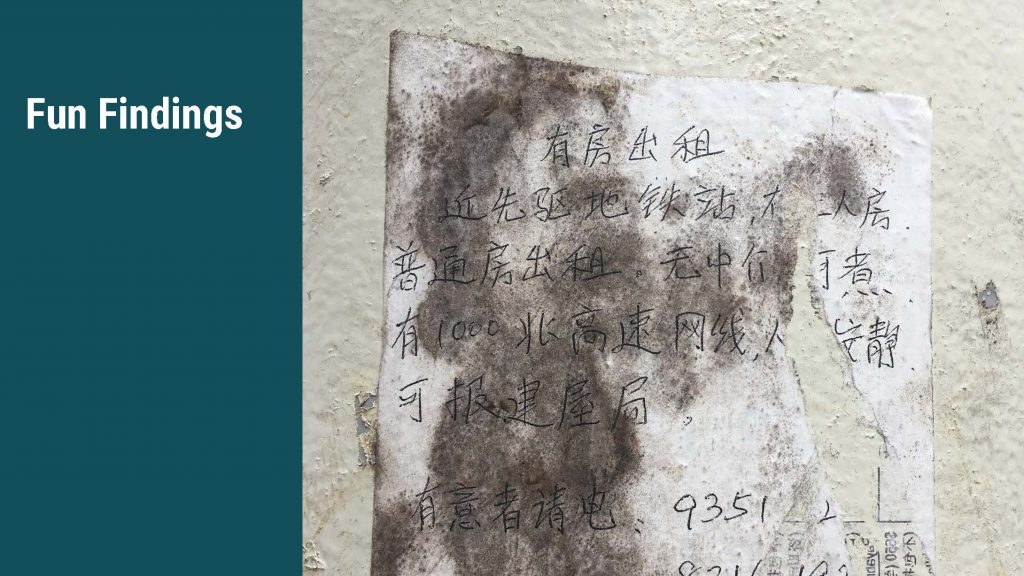

UX: Chipchase “You Are What You Carry”

Jan Chipchase’s “You Are What You Carry” chapter was a relatable followup read to his TedTalk on the anthropology of mobile phones. He elaborates on the four factors of security, convenience, reliable solutions and peace of mind that drive our carrying behaviors. These factors are inherently connected so that lack of one directly degrades another; for instance, if I feel my purse is not secure enough for the place where I am, my peace of mind will diminish. This is undeniably affected by someone’s environment at any given moment and how we prepare and react within that environment. Chipchase calls this phenomena – of determining how confident we are in the security of a situation so as to project how protective we need to be of our possessions – the range of distribution. What struck me was how this might be a conscious or unconscious effort to guard your belongings. Every person instinctively does so as a result of distrust of others and the danger we perceive in an environment.

Thus, the environment is the driving factor in how we carry items. A month living in Singapore has lessened my paranoia around my items being stolen compared to that in the United States. However, being in a foreign location where items are not so conveniently replaceable and may even be more necessary (i.e. a passport that cannot be instantly replaced) heightens a person’s tight range of distribution. Still, our range of distribution is affected by much more than just the country we are in. The neighborhood we are walking through, the cleanliness of the area, the people in a space, past records of theft in the location, and the items we are carrying are all factors in how closely we hold onto our belongings. Clearly, it would be easier to have fewer items to keep track of within your range of distribution – thus, the convenience of the mobile phone. But the mobile phone goes much farther in providing infinite data so that we can access inconceivably more than we would be able to physically carry at any given moment, so long as technology is reliable.

Reliability and security are two of the greatest flaws in creating digital equivalents of our belongings to “carry” around with us. People desire convenience and efficiency so much that with stronger technology it becomes a game of risk in how willing we are to put personal information on a digital database. Technology with greater capabilities to understand and predict human behavioral patterns means machines and technology are becoming more human. Vice versa, humans start giving up freedom and (physical) control of their belongings or information they own. Chipchase states that “People are risk-averse” so they would never give up so much control of their belongings that they would “be at the mercy of the network”. The trajectory of technological advancements and society’s sense of security, convenience, reliable solutions and peace of mind seems to almost be at a halt in terms of figuring out how to find a balance between all four factors. Yes, our behaviors tell us that we are what what we carry. But that is void without considering the context. Ultimately, I wonder if it is wiser to invest in increasing the security, reliability, convenience and efficiency of city infrastructures over that of the products we carry.

Field Study Presentation – Public Spaces

Sounds of the City Mixes

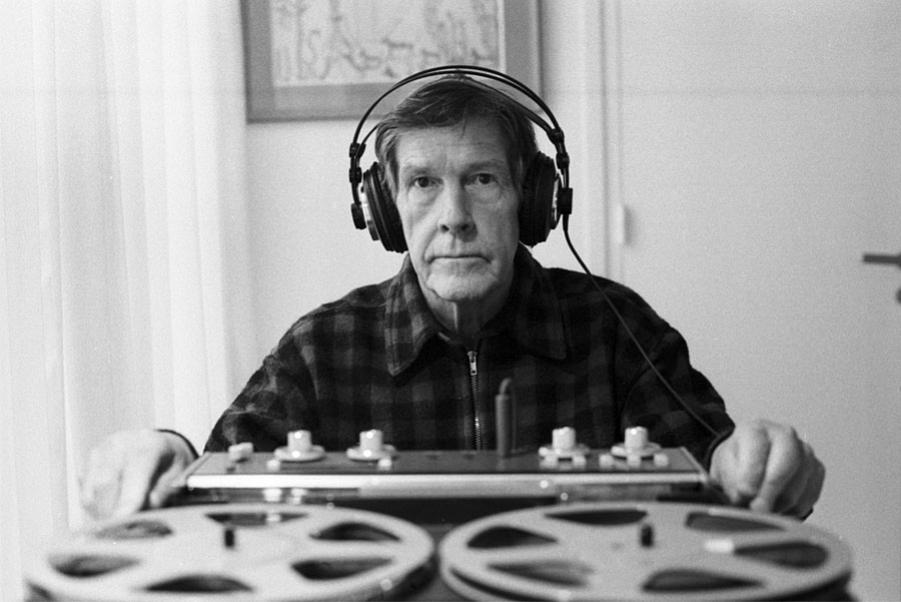

Sound: Response to John Cage’s “Silence”

History is often read as context for understanding the present. Yet, in John Cage’s “History of Experimental Music in the United States,” he spends the first four paragraphs renouncing history:

“Why, if everything is possible, do we concern ourselves with history (in other words with a sense of what is necessary to be done at a particular time?”

Instead he proposes, that:

“one does not seek by his actions to arrive at … success… beauty… [or] truth[,] but does what must be done.”

While this seems to contradict any sense of purposeful composition, the theory makes sense in combining noise sounds that may simply be noises that are heard in everyday life — noises combined without artistic intent. Accepting this lack of control can be quite difficult for the designer’s mind in someone like myself, which attempts to design a concrete solution to a problem.

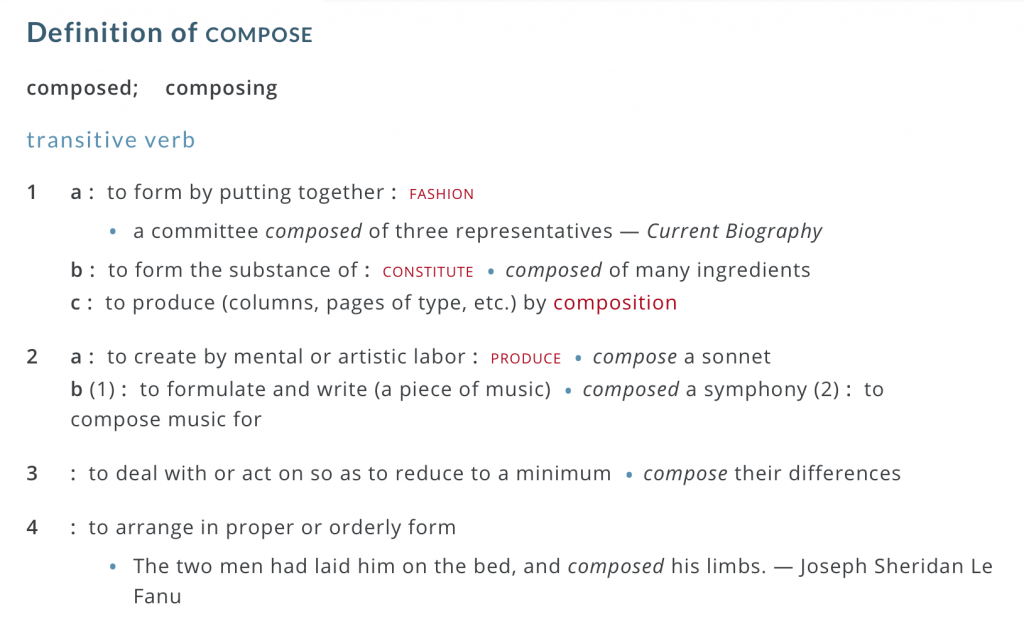

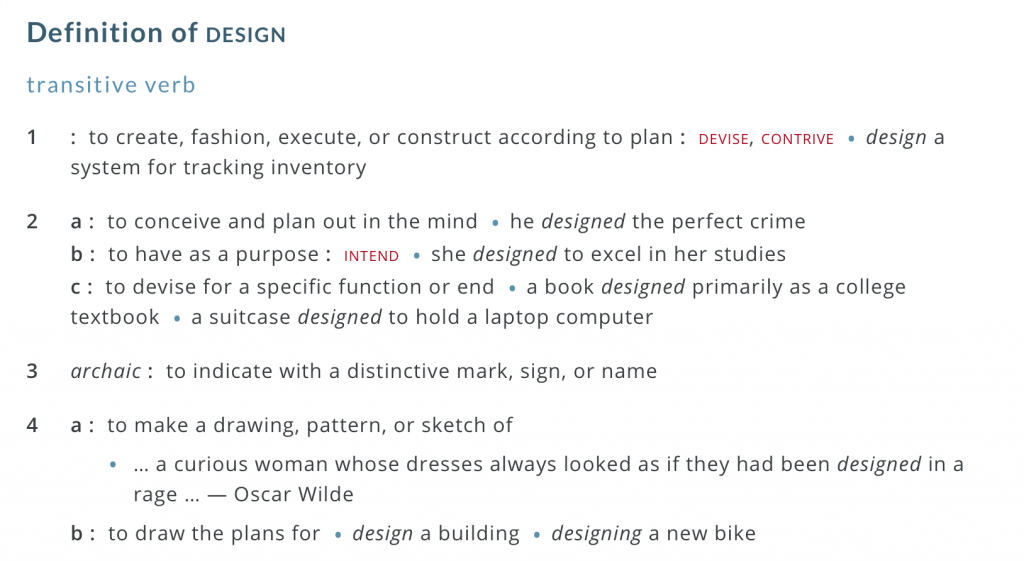

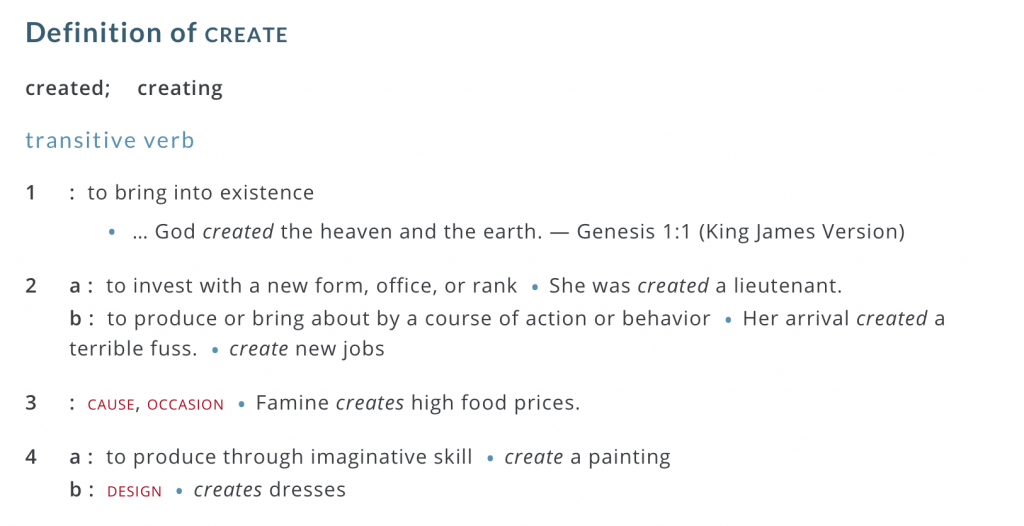

Reading Cage’s writing after reading Edgard Varese’s “The Liberation of Sound” gave me a greater appreciation for how advanced Varese was for his time. Still, Cage criticizes Varese as being not experimental (or varied) enough in the outcome of his sound compositions. Cage’s focus on chance operation and lack of preconceived notions seems to be a reversal of how we compose, design, or create.

Out of the three of these terms, I would deduct “create” to be the word that fits Cage’s proposal for experimental music best; yet, creation typically exists through use of the imagination and Cage reject’s Varese’s use of the imagination. His extreme opposition to history and purpose in music is quite intimidating in envisioning how myself or anyone might compose such music based on indeterminacy.

On the other hand, composing silence seems to be accepted by Cage and planning for space and emptiness is an idea that easily translates across much of art and design. Maybe Cage is proposing that we abandon commonly accepted ways of planning and strategically composing sounds and approach compositions from new angles. We can still write pieces with intent but then flip the composition or erase parts or find other means that would result in an outcome that wasn’t originally conceived. Possibly, experimental music might simply be about letting the sounds drive the composition and being open to however the sounds combine themselves…

“Giving up control so that sounds can be sounds”

This brings up the concept of what is considered sound versus music, which we have explored in each reading so far. If we let noises drive compositions, does that mean they are still musical compositions? One of John Cage’s most famous pieces, 4:33, pushes this to the extreme with silence as sound.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTEFKFiXSx4

With 4:33 as my point of reference, listening to Cartridge Music actually emphasized “silence” as sound, or as Cage points out in his writing, the importance of emptiness. Even with earphones in while listening to Cartridge Music, I could still hear the background sounds of the cafe I was in: the workings of a kitchen, the people sitting next to me, distant cafe music, silverware clinking:

And yet, these surrounding noises added to the experience of the listening to this piece of inconsistent rough mechanical sounds. Silence allows each listener to have a slightly different experience while listening to a composition. Essentially, through 4:33, Cartridge Music, and his writing, Cage puts a focus on time, unpredictability, and the constant noise surrounding us as the only requirements to successful experimental music.

UX: Jan Chipchase TED Talk “The Anthropology of Phones” Response

Even though Jan Chipchase’s TED Talk on “The anthropology of mobile phones” was given ten years ago, many of his points are still relevant today with slight adaptations. Today more than ever people keep their phones close to their person more than any other item. As I walk out my door, I catch myself double checking that I have my wallet in my purse or backpack and tapping my pockets for my phone. The phone is the most valuable possession of people as it is a global communication device, virtual wallet, infinite source of information, immediate source of social media and much more. Chichase’s point on the three items people always carry is still true today and proves the importance of communication, shelter and security in our daily lives.

However, these safety and psychological needs that are fulfilled through carrying our mobile phone make me question whether it is the phone that is really needed or just any sort of object that could fulfill all those needs at once. Of course, this item must be digital and have varied capabilities or infinite capabilities in terms of information sourcing. Laptops provide all the same features a phone might but the phone is more convenient for daily use and on-the-go lives. Watches are another item that have begun to provide these same capabilities that our phones might provide while functioning as an object we might already have on us instead of an object we must keep in our pocket or purse. Still, the cell phone is currently the better tool with its size, screen, and worldwide use. Though as more products are designed to be “smart”, it begs the question whether the phone really is the most convenient tool for providing humans the ability to communicate and a sense of safety and security all the time. The phone is always evolving as seen in the slightly dated examples Chipchase brings up such as 2007 Uganda Sente, but if we stick to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the learnings from these examples are still applicable. Ten years from now, we shall see what new technological developments have or have not superseded the cell phone as peoples’ most valuable possession.