Golan Levin, recalls making his sound piece Dialtones as

“deliberately treading the fuzzy boundary between music and noise,”

words I believe could be applied to all of the people we have studied in this class to a degree. Pushing the boundaries of composition and music and stretching the accepted view of what sounds are pleasing to the ear seems to be a recurring theme each week as we discuss sound artists.

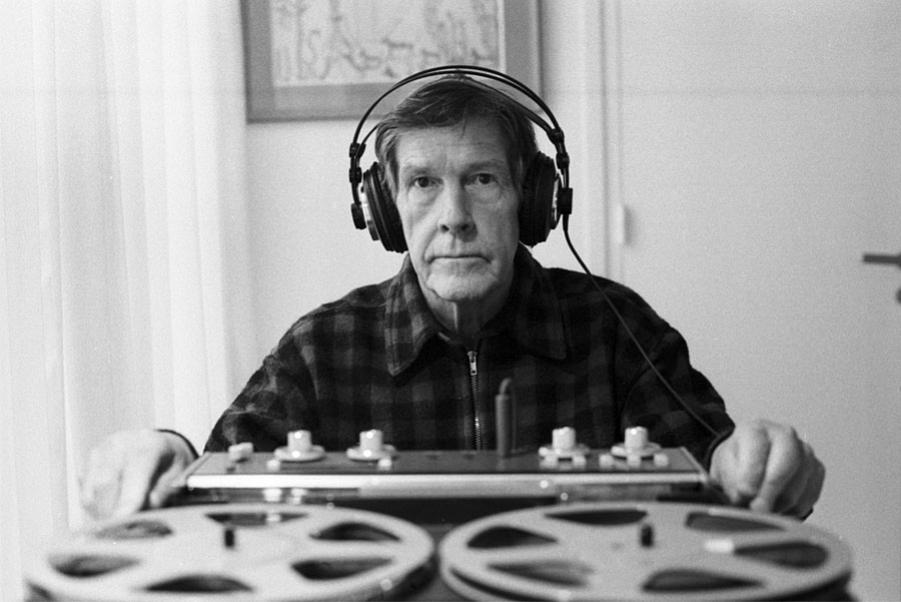

In the interview, Levin references John Cage’s influence on the experimental and unpredictable nature of his music multiple times. Many aspects of using digital sounds produced by technology are unpredictable in nature, especially when these sounds are produced by a person’s main communication device. Who knows when someone will next be contacted through their cellular device? Levin recounts numerous instances of unpredictable happenstances but does not seem to view these as mistakes in the performance, but as chance elements that heighten contrast for the composed solo section of Dialtones. This idea of letting whatever sounds happen to occur be a part of a performance piece is quite similar to the mindsets of Bill Fontana, John Cage, Edgard Varese, and even all the way back to Luigi Russolo.

Most intriguing, Levin makes a bold statement that

“the days of purely random music were over”,

defining music composition as the ability to effectively manage this randomness. It seemed Levin moved away from this randomness more than he even realized because of the human control in decision making he utilized during the performance. He purposefully chose people to shine light on during the performance and trigger their phone, instead of using

“an abstract sound-triggering system, [inadvertently making the performance] a communications medium that connects people.”

This may have connected him to individual members of the audience as he triggered their phones as musical instruments, but it erased the thought of complete randomness from the performance entirely. Instead, Dialtones is more composed than most pieces we have looked at in class so far.

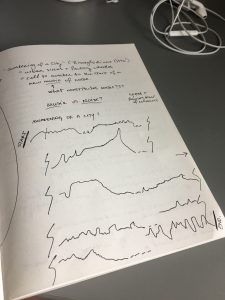

As I started to read this interview, I was immediately brought back to one of my first ADM assignments in which we had to pitch a large-scale interactive piece. My group focused on human interaction in controlling sound in an exhibition space which turned into a performance space as sound was thought of as organized and composed. We had decided to pitch the idea of using audience members phones in a circular auditorium that would be programed to play musical sounds controlled by a center computer. The idea was quite extravagant and also proposed controlling the flashlight on phones so that the performance could simultaneously be a light show during which sound and light would emanate from each individual person’s seat. Thus, audience members would ideally feel they are a part of the performance — similar to Dialtones in many aspects I am now realizing. However, in both instances, the level of interaction with the audience can be questioned. People are not touching or interacting with their own phones at all, especially when compared to the level of interaction in Thomson & Craighead’s Telephony. It makes me think how connected are to our phones… so much so, that we feel we are participating in a performance just because our possession is being controlled by a computer or in Dialtones‘s case, Levin and his software.

Listening to Dialtones is a very familiar experience as we hear sounds around us daily, although escalated in the performance. I think most people find these sounds that phones emit to be annoying, not because the sounds are annoying themselves but because it seems somehow offensive to emit a sound every time you get a social media notification, message, call, et cetera. Thus, most people keep their phones on silent or vibration or low volume. But I imagine that if a group of people in a densely populated space all turned their phones on full volume for all notifications, the resulting sound would be very similar to Dialtones. The main difference of course being the compositional techniques used in Dialtones that make it more like a musical performance than ambient digital noise.