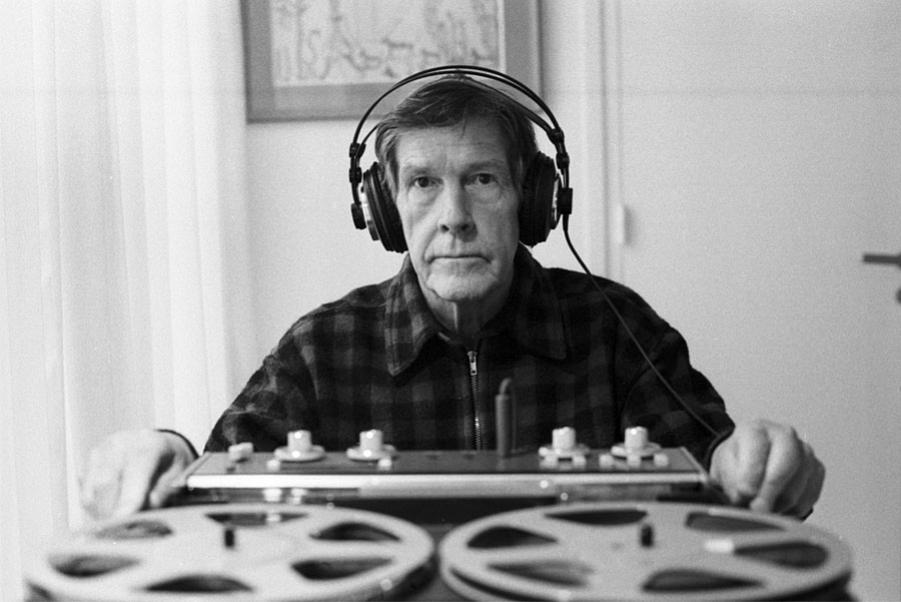

History is often read as context for understanding the present. Yet, in John Cage’s “History of Experimental Music in the United States,” he spends the first four paragraphs renouncing history:

“Why, if everything is possible, do we concern ourselves with history (in other words with a sense of what is necessary to be done at a particular time?”

Instead he proposes, that:

“one does not seek by his actions to arrive at … success… beauty… [or] truth[,] but does what must be done.”

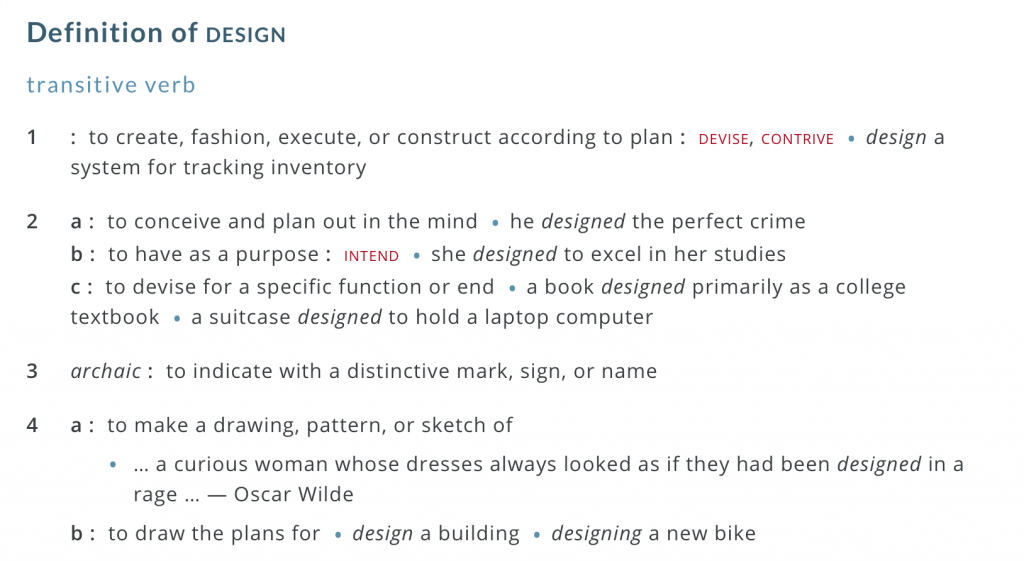

While this seems to contradict any sense of purposeful composition, the theory makes sense in combining noise sounds that may simply be noises that are heard in everyday life — noises combined without artistic intent. Accepting this lack of control can be quite difficult for the designer’s mind in someone like myself, which attempts to design a concrete solution to a problem.

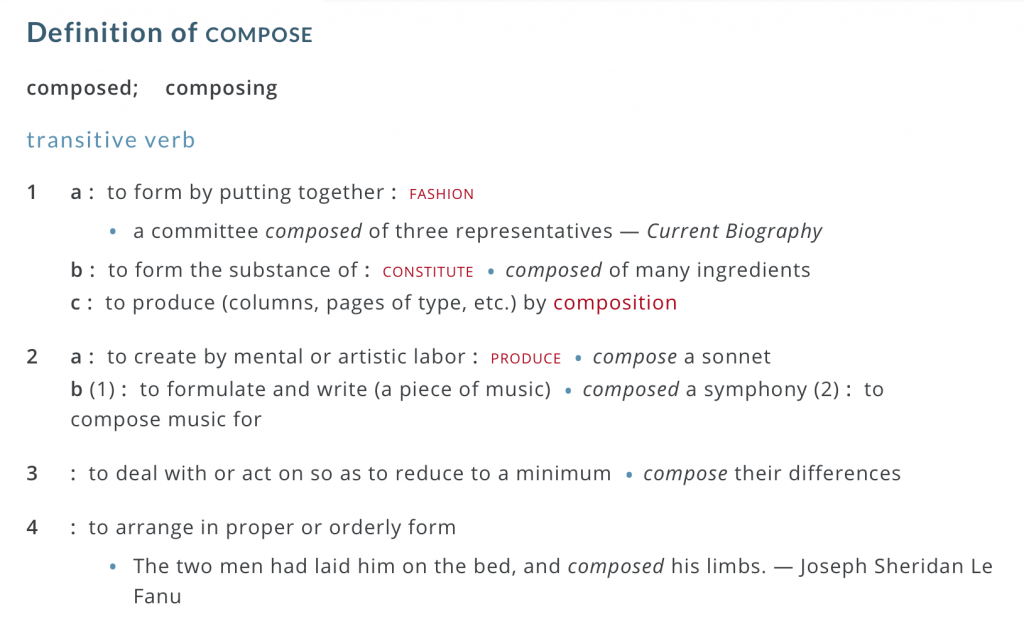

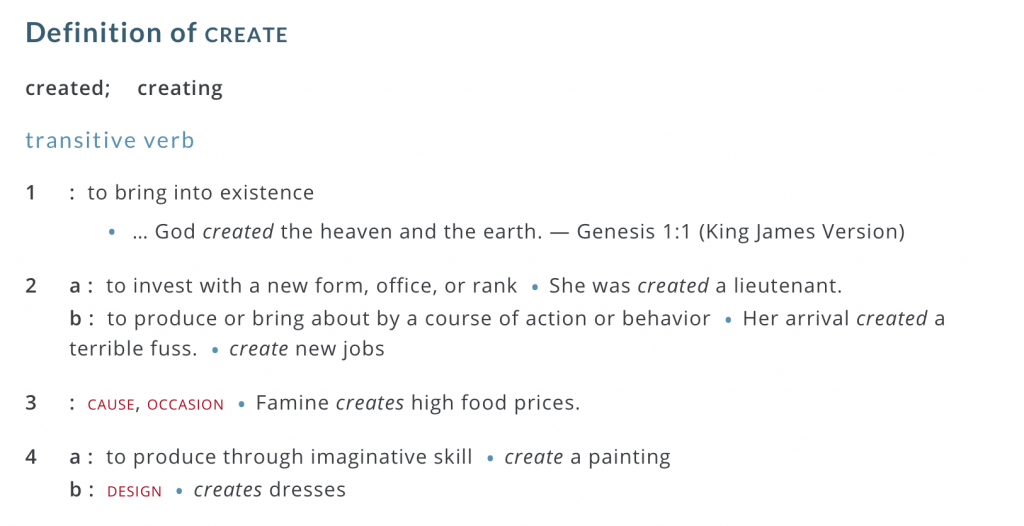

Reading Cage’s writing after reading Edgard Varese’s “The Liberation of Sound” gave me a greater appreciation for how advanced Varese was for his time. Still, Cage criticizes Varese as being not experimental (or varied) enough in the outcome of his sound compositions. Cage’s focus on chance operation and lack of preconceived notions seems to be a reversal of how we compose, design, or create.

Out of the three of these terms, I would deduct “create” to be the word that fits Cage’s proposal for experimental music best; yet, creation typically exists through use of the imagination and Cage reject’s Varese’s use of the imagination. His extreme opposition to history and purpose in music is quite intimidating in envisioning how myself or anyone might compose such music based on indeterminacy.

On the other hand, composing silence seems to be accepted by Cage and planning for space and emptiness is an idea that easily translates across much of art and design. Maybe Cage is proposing that we abandon commonly accepted ways of planning and strategically composing sounds and approach compositions from new angles. We can still write pieces with intent but then flip the composition or erase parts or find other means that would result in an outcome that wasn’t originally conceived. Possibly, experimental music might simply be about letting the sounds drive the composition and being open to however the sounds combine themselves…

“Giving up control so that sounds can be sounds”

This brings up the concept of what is considered sound versus music, which we have explored in each reading so far. If we let noises drive compositions, does that mean they are still musical compositions? One of John Cage’s most famous pieces, 4:33, pushes this to the extreme with silence as sound.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTEFKFiXSx4

With 4:33 as my point of reference, listening to Cartridge Music actually emphasized “silence” as sound, or as Cage points out in his writing, the importance of emptiness. Even with earphones in while listening to Cartridge Music, I could still hear the background sounds of the cafe I was in: the workings of a kitchen, the people sitting next to me, distant cafe music, silverware clinking:

And yet, these surrounding noises added to the experience of the listening to this piece of inconsistent rough mechanical sounds. Silence allows each listener to have a slightly different experience while listening to a composition. Essentially, through 4:33, Cartridge Music, and his writing, Cage puts a focus on time, unpredictability, and the constant noise surrounding us as the only requirements to successful experimental music.

Excellent. You bring up so many good points. I was particularly drawn your statement that with silence, everyone has a unique listening experience. So true! At this point, the experience is highly participatory, because everyone, in a sense, is composing their own “music” to fill the void of silence that Cage has created. I also thought that this was a good comment:

Yes, Cage was very interested in freeing the sounds (and our ears) without historical baggage and pre-conceived notions of habit and taste. In a sense you are right, that the sounds are driving the composition, but also, he freed the compositional process using chance as a way of driving the sounds, or perhaps liberating the sounds from the composer’s control.