From two months studying at NTU, my perception of design has definitely changed. Projects I have been exposed to in all of my courses have been much more than visuals on a poster or screen. The experience of interacting with media is multi-sensory and through this class, so far, I have learned how sound augments an experience in a particular space, shared with others or alone, or while interacting with an art installation. Emotion, purpose and innovation associated with interactive media is very much a result of sound.

One of my first realizations in August came from Futurist Luigi Russolo’s manifesto “The Art of Noise.” Russolo believed that

“the rhythmic movements of a noise are infinite.”

Thus, we should make every attempt to

“break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.”

Of course, every noise has its own unique sound but Russolo blew the door open for the infinite sounds we could CREATE ourselves. As I explored combining recorded noises in Max and utilized various output modules, it become quite obvious how expansive the sound landscape is.

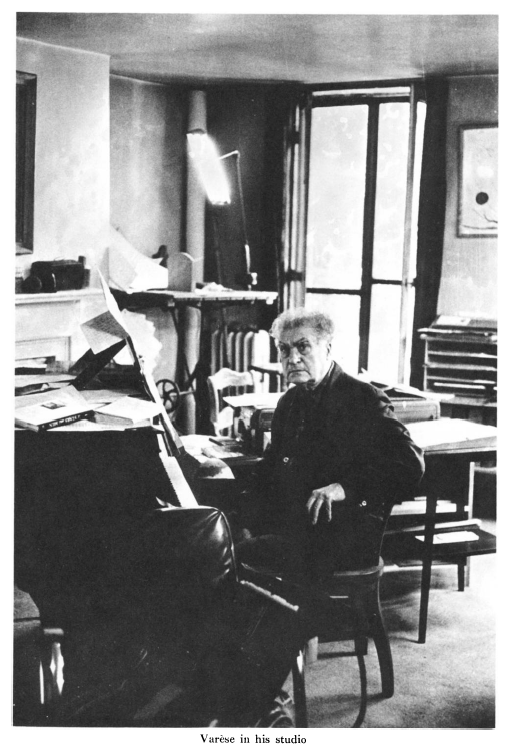

So where does one begin in producing a sound? Is it entirely fabricated from scratch like the sounds produced from Russolo’s noise machines? Or is it experimental use of instruments that already exist, as composer Edgard Varese practiced in his piece Ionisation? For the purpose of my project, I was inspired by contemporary sound artist Bill Fontana’s use of everyday sounds, recgonzing that

“the world at any given moment is a potential musical system.”

Listening and observing are a couple of the most important skills in learning and finding inspiration in our daily lives. As I went about my days here in Singapore, I did not actively search out moments of sound inspiration. Rather, it was in the times when I was just being present in a space that I would pick up on a soundscape around me that I wanted to record. These sounds were then combined to become half of my compositional audio-visual piece, layering each of these moments on top of each other to create a new sound landscape.

Yet, with all I had learned about finding and producing sounds, composing them posed a greater challenge. Harkening back to Russolo’s “Awakening of a City”, it appeared that noises could become a musical composition as we try to organize them in a strategic manner. There may be no recognizable form of composition exactly like that of musical notes; but the freeing of sounds as they collide on a three dimensional plane, explained by Varese, creates new colors, magnitude, and perspectives so that

“the entire work will be a melodic totality. The entire work will flow as a river flows.”

Layered sounds, reverberation, additive filters, and changing volumes moved the individual sounds towards a calculated composition in our projects, abandoning linear movement of sound masses. And while what we were creating in class was an entirely conceived sound composition, there are similar sound mass compositions that we experience around us. Go to a hawker center or cafe, a public concert or sports event and you will be able to pick up this textural mass of sounds. Yet we don’t always do so. We pay attention to what we see more so than what we hear. Our reading from composer John Cage on silence, helped me acknowledge that listening is as powerful as seeing or creating.

That is not to say that video should be disregarded. But because we are constantly focused on the visuals in front of us, video feed can make sounds more recognizable and less imaginative. Thus, used wisely, video can help root a composition in narrative. Visuals add depth to a soundscape just as sounds add dimension to video. Combined together, they form what a digital landscape truly is: an immersive experience in a composed story. Artist Janet Cardiff showcases how sound and video can distort time in a listeners mind, relocate people from place to place and open up alternate worlds,

“where reality and fiction meld.”

This alternate reality is what we attempted to create in our digital landscapes.

Whether it’s traditional musical notes or experimental noises, music reflects the world. It reflects the way in which the artist intended a sound piece to be heard. It reflects the thoughtful innovation of unique sounds that have been put into the world. And music reflects the emotion of the listeners and authenticates our experiences. Through our digital landscapes, we are able to take these reflections and our learnings on conceptual sound art to evoke new stories with creative purpose.