Kadenze is an online learning platform “developed to benefit students and faculty members of the creative arts“.

A preliminary analysis of the course syllabus for “Introduction to Generative Arts and Computational Creativity“, suggests that learning is framed by structures of learning about, rather than learning through doing or performance, as there is no indication of how Kadenze itself can be used to evince learning by Doing it With Others (DIWO).

Course DESCRIPTION

There is mention of the course providing “an in-depth introduction and overview of the history and practice of generative arts.”

It “offers an ontology of the various degrees of interactivity and generativity found in current art practices”, and “surveys the current production in the field of generative art across creative practices”, to “introduce the various algorithmic approaches, software, and hardware tools being used in the field”, and finally address “relevant philosophical and societal debates issues associated with the field”.

Assessment:

Projects 60%

Quizzes 30%

Assignments 10%

Quizzes suggest that learning is framed by the acquisition metaphor, where Kadenze’s primary function appears to be facilitating content transmission by the “course instructor” (didactically “instructing” learners, rather than dialogically and reflexively guiding, facilitating and discussing), who aims to test learners’ recall ability of delivered syllabus content.

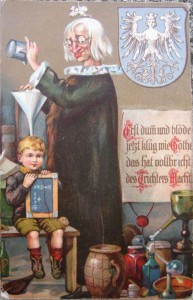

As if learning in the creative arts can be engendered mechanically transmitted or digitally transferred and hence acquired by learners via the metaphorical Nurnberg funnel, illustrated below.

Delivered content does not engender learning, just as learning about swimming differs from learning swimming. Learning Generative Arts and Computational Creativity by doing, requires learners to generate art and compute creatively, through Kadenze, as the the mediating technology or online medium.

Like OSS, the Kadenze course designer could go beyond learning by doing, by facilitating learning by Doing It With Others (DIWO) as a Computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) technology.

The Course Designer’s Philosophy of Human Learning

It is abundantly clear that like OSS, Kandenze has the potential for CSCL-facilitated learning by DIWO, but this technological affordance, cannot be fully exploited, if the course designer stubbornly clings onto Cartesian and empiricist epistemologies of learning that are oriented towards outcomes (rather than process) and advocate instructing, training and conditioning, for knowledge acquisition, retention and recall (rather than learning by doing).

It is thus imperative that course designers reframe their notions of learning, in order for the full range of potentialities afforded by technologies such as OSS and Kadenze, to be more widely accepted and realized.