Overarching Thoughts

In this chapter, Gaston Bachelard suggests that we intuitively are phenomenologists when we fantasise about the entity that a Nest is. Scientifically, a nest is a drab structure meticulously made up of leaves, twigs or other materials for a specific function — to serve as a space of refuge and shelter for birds and their nestlings. However, as humans we constantly ponder about the spirituality of the world we inhabit and the significance of our presence in this fundamentally infinite ‘space’ — space is infinite in the way it pervades and navigates through structures we have created to artificially compartmentalise and ‘control’ it. We in a sense, make ‘places’ out of our space, assigning them with specific functions to make sense of our being here. However as beings, with the ability to have experienced profound emotions, coupled with our highly advanced cognitive functions, we subconsciously are unable to ignore the fact that space as a concept is non- tangible and noetic. Space is the basis for our origin — time after all is considered a dimension of space in quantum physics. Essentially space is not physical; it is ‘nothing’ yet it is the overarching and primordial principle that allows matter to exist and exert its effects. Space is nothing, yet without space nothing can exist.

Personal Thoughts (on nests)

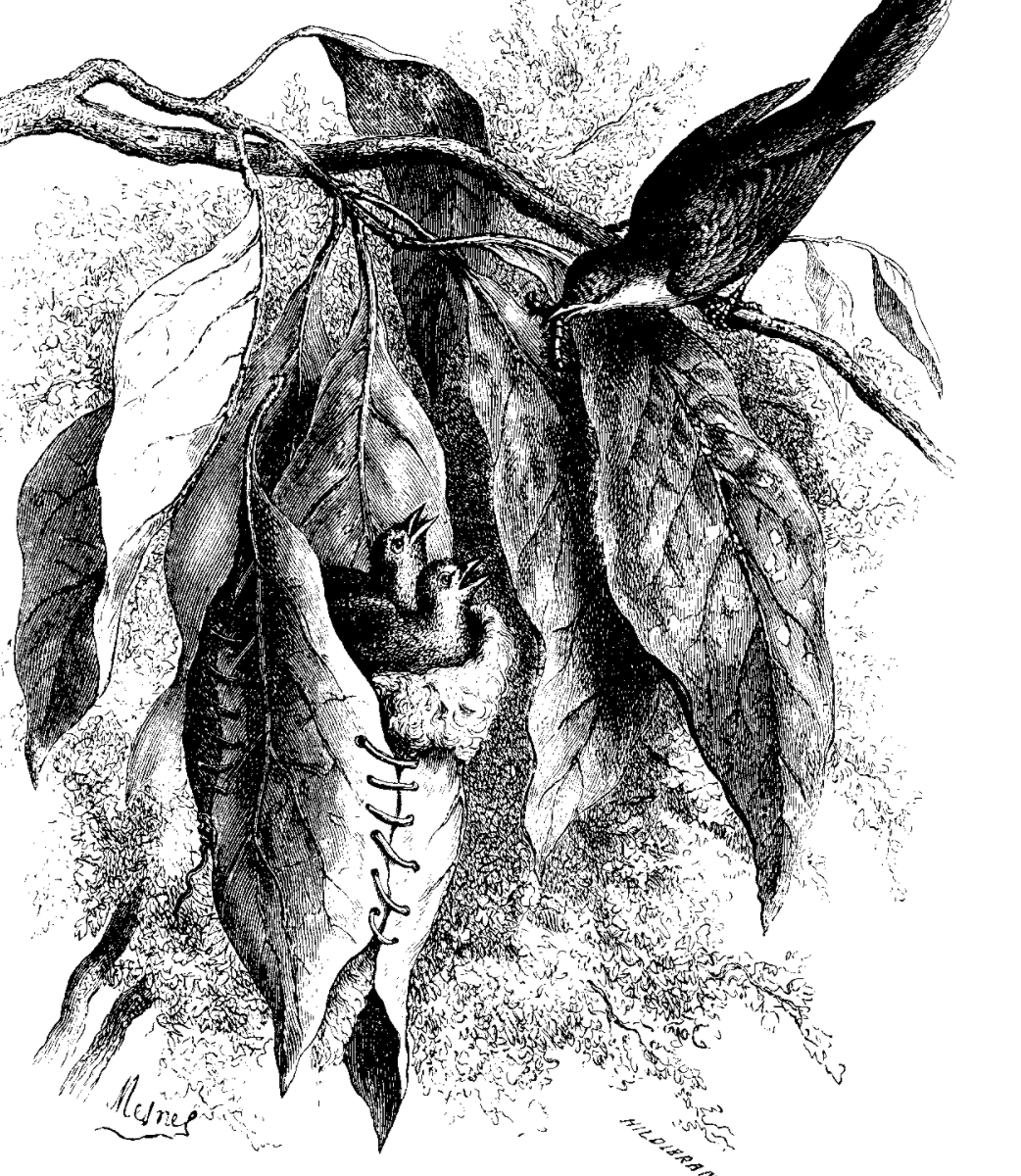

In the chapter Nests, Bachelard specifically explores how we apply this noetic intuition of space to our perception and interaction with Nests. A nest after all is the abode of a bird. Our abode is our room, flats, house etc. Why then do we have this innate propensity to associate our idea of ‘home’ with a nest? As stated in the chapter, many poets and artists have also made this reference to nests when describing the space they inhabit. We do not know at all what it feels like to be in a nest. What we perceive it to be is based on our own senses’ interaction with it.

Sight :

Nests are predominantly snuggled in corners, hidden and safe. They often mimic and blend into the space they inhabit as materials obtained by its builders (birds) of the nest are sourced from the vicinity. Even in highly inorganic and structured spaces like the crevice of a wall, the imagery of a nest evokes a sense of comfort. The way it organically camouflages and fits into the space it occupies, like scaffolding, permeates a sense of belonging and warmth. Even when we see nests built in all sorts of places in the concrete jungle we inhabit, we do not immediately feel that they are out of place. It is this rootedness yet adaptable nature that draws us to fantasise about how we perceive our ideal home to be — we want a permanent dwelling, yet one that comfortably sits into the space it occupies.

Touch :

Nests are often soft and fragile. They are made with fine twigs and are light. When we touch a nest (many of us probably have out of curiosity, as the author has mentioned), we not only feel it’s exterior, but we feel it’s recesses, or explore the negative space (interior within). We are highly aware of the mutability of these ‘dwellings’ due to their fragile structure. Hence we are careful and cautious when we approach it, fundamentally imbuing it with ‘safety’. Think about the way we approach bird nests as opposed to ant nests. Most of us have probably desecrated ant mounds mercilessly because of our mental association of its inhabitants with pests. Though fortified, ant nests are deliberately destroyed compared to bird nests which are completely vulnerable and exposed yet protected from destruction by our own reservations and sentiments. This is perhaps why we dream of nests being our homes or refer to our dwellings as ‘nest’. (because of the space it occupies in our mind as being an undisturbed and safe refuge.)

Sound :

A nest with hatchlings, emit chirping noises, making the presence of life known. Even when we are unable to see what is inside of these nests, psychologically this notion of chirping, hungry, fragile nestlings invoke an idea of occupancy — we may not even know if a nest is empty or occupied yet we intuitively tend to believe the latter. We do not directly have to had seen a nest to develop this perception — documentaries, books etc have all cultivated this notion strong enough.

Personal Thoughts (on birds)

Birds are like Gypsies, they are free to fly around and make places out of any space they want to, regardless of the consequences that might occur from doing so. We however do not have this luxury fundamentally due to our anatomy. We do not have the ability to simply fly wherever we want to and conveniently build a ‘defined space’ with surrounding materials. We are also too physically ‘large’ to do so. Hence, this portability and possibility is only something we can dream of, supporting the proposition that we tend to treat nests as phenomenologists.

Apart from being restricted by our biological anatomy, we are also restricted and bound by societal rules we have created. We need money to build and purchase a ‘home’, or money and authority to secure a piece of land. We do not have the rights to make any space of our choice our ‘home’ despite space in itself being an unquantifiable entity — we have made it measurable by creating structures, buildings, rooms, that dissect it, creating artificial enclaves that allow us to allocate it. We are hence all limited by these ‘places’ and can only navigate in specific directions — we cannot walk through a wall even if we wished. Birds however can simply hover over these structures freely, having full access to all the space there is out there. By associating our homes with nests, I imagine we wish to recreate a nest like space, albeit artificial, one that evokes this sense of freedom. These are expressed in the form of SOHO apartments with high ceilings or Glass Facades etc.

Concluding thoughts

Thought I can relate and identify with the idea of associating nests to homes and in our dreams, it is significant to note that how we often view other places or rather spaces made into places, is based on our own experience, emotions or perceptions. The idea of ‘home’ is universals. Though varying in structure, geographical location, or aesthetic appearance, the ideal notion of inhabiting one that encompasses the ‘spirituality’ and ‘poetics’ of a nest is possibly universal and intuitive. This however does not apply to spaces we do not consider to be our ‘abode’. The perception of these other spaces we walk into and explore, are more rooted in our unique interaction with the world, moulded by our own experiences. For example, a person suffering from PTSD may associate the space of a clinic with trauma while a nurse might associate it with familiarity and comfort.

Endnote

Here is a descriptive anecdote I wrote awhile back, expressing my perception and phenomenological associations of the space of a LGBT Bar in Chinatown :

“On nights like this, the ivory coloured tiles shimmer like scales of a mythical imaginary creature. A creature conjured up with such immense conviction and self belief that its seemingly delicate eccentricity and ‘out of place-ness’ endowed it with a sense of impenetrable boldness and authenticity. It’s scarlet red inner walls which reverberate with exuberance and passion, coupled with heady dance records from the colourful 80s attract characters of all kinds- some curious for a taste of the unfamiliar while others longing for the regular opiate of being amongst their own ‘kind’.

Through the gate, a young walks in, and eyes dart quickly to steal a glance before shifting back as inconspicuously as possible to preserve their ego driven feigned nonchalance. After all they were all in their own capacities, subtly hoping to garner the ‘spotlight’ in a predominantly male ‘playground’ that embodies both the veracity of masculinity and the sensuality of femininity. This potent fluidity permeated through the bar – a ‘Shangri-La’ for those who lived within thinly defined boundaries.

He keeps his gaze forward and walks briskly down the long walkway wedged between the two rows of crowded tables. His well built body gave each step he took with his leather boots a compressed weight. Yet there was a hint of effeminacy in the way his feet moved, with such perfect rhythm and swing, that one’s senses could be coaxed into believing they were watching an androgynous model parade down a runway. It took a calibrated degree of spacial awareness, spontaneous judgement, and calculated confidence coupled with seasoned practice, to exert this sort of presence in a place that was so ‘loud’.

It is past midnight now and the buzz of the crowd starts to blend in with the music from the Madonna, Cher and other Diva produced numbers that play on the screens. Ash trays get increasingly vandalised by wet cigarettes – some pre maturely stubbed out, perhaps in a rush to head upstairs and others left with just their alcohol stained butts, probably fully savoured within the span of casual small talk with strangers that called for the help of an anxiety mitigating drags of nicotine or intimate conversations that needed a stabiliser wedged between quivering lips or fingers.

The young man makes his way up the central carpeted crimson steps that lead up to the heart of the bar. Framed portraits of immortalised icons such as Marilyn Monroe and Judy Garland, and pin up style cult classic posters line the green walls like enchanted talismans that have been plastered all over to bestow upon this place its quaint charm. The portraits aren’t just icons but worshipped idols that somehow emanated the fearless self empowering energy one needed to embody to feel as free as they were allowed to be in this ‘temple’. As he reaches the end of the carpeted steps he is immediately transported into a luscious gaudi gilded interior that looks like it belonged in Mrs Manson Mingotts Mansion from Edith Wharton‘s Age if Innocence. Everyone here are self made characters with interchangeable roles — a seductress , a damsel in distress, an innocent boy, a lonely man seeking companionship. They could be whoever they wanted to be whenever they wanted to be.

It was an open stage where even a seductively wielded billiard stick could be a prop.

It’s after all synonymous with the character of its residence – a melting pot of multicultural and multi religious landmarks.”