Words

Dominance, Transience, Restraint, Comfort, Obligated Rootedness.

Personal Reflections & Analysis of ‘Space’

1. My Room (Dominance)

In my home, I share my room with my brother with our beds set apart, flushed against each side of the wall. I personally do not have a good relationship with him and more often than not, we only speak when we need to. This discomfort and tension in one shared space that has no physical divide has inherently prompted me to come up with interventions in order to artificially or psychologically demarcate my own space or my ‘half of the room’ to create a comfortable area for myself. Silence, amplifies the awkwardness when both of us are in the room. Silence can be peaceful and calming but an awkward kind of silence gets under your skin. One way of establishing my dominance over my space sometimes would be me turning up the volume of the music on my speakers. Sometimes this draws some retaliation and he turns his speakers up too. We don’t physically content for our own spaces in this shared area but it is interesting to take a step back and analyse how the pervasive nature of sound is powerful enough to assert spatial dominance. Imagine if you were sharing a room with someone who hates classical music and you crank your speakers up to the max with the sound of an orchestra; it’ll either coerce the person into naturally wearing their headphones — a sign of suppression and surrender, or walking out of the space entirely to the main hall (in defeat).

Most recently I installed fish tanks right beside my bed and although they don’t fully split the room in half, the presence of some physical ‘wall’ or barrier further establishes my side of the room, psychologically making me feel more comfortable. The tanks have this iridescent blue night light that illuminates the walls at night — in some sense while being stationary, that personal object with its light attached, then projects itself onto the entirety of the room, marking territory of my presence.

2. ‘Home’ out of the ‘House’ (Transience)

As I have been staying in Hall at NTU now, I rarely go back home as I live all the way in the east. I am also someone who prefers socialising with people a lot and am often outside. Hence home to me is just a transient place with innate strong memories. The idea of ‘home’ is not limited to any physical space. One could consider any safe space their ‘home’. More importantly the space we inhabit and we often refer to as home is a ‘house’, a clearly defined physical space in which we co inhabit with our family members.

My idea of home is transient as I find ‘home’ in places I’ve had significant memories with people — rooftops, coffee stops, water banks, the bench at East Coast Park; all these at one point in my life were landmarks that I shared with someone important, a place of intense emotion and they have nostalgic tentacles tethered to me. In each phase of my life, there was some place I would visit to feel good, or safe if I needed to just sit and ‘exist’. One really significant place is a small rooftop at Greenwich — a place I spent a lot of time in, with my best-friend, the only person I’ve ever called my soulmate. The emotions tethered to this space are so strong that even though it has been physically closed off by authorities, it occupies a psychological space in my mind and I do not have to physically travel there anymore to feel the comfort I derive from being there.

I quite simply can think of it, look at curated pictures of it on my phone album, and reminisce in the moment and the details of our marks left behind — spit stains, cigarette ash, prints from our shoes etc. The power of the human brain; its memory and the way it creates association via all its senses enables us to own spaces we don’t physically own. It gives us the ability to enter these spaces in our heads. Fragments of sensorial memory — smell of the flowers, sound of the cars whizzing by, the colour of the blocks that form the skyline, the shade of the trees planted there, all amalgamate together to form a virtual yet profound realm that we can freely access whenever we want, for life, regardless of the physical permanence of the space.

Here is a poem I wrote for my friend with the imagery of the rooftop in mind:

3. ‘Home’ in the ‘House’ (Restraint)

In the same way, growing up in a house in your formative years leads you to associate emotions to certain objects or spaces. I never had a good relationship with my brother and was not so close to my parents as I was mostly brought up by domestic workers while they were working. Love was not explicitly conveyed but rather translated via obscure actions or mechanisms — a very Asian thing I suppose. (The inability to express love or rather the awkwardness of having to express love without using assertion and chiding as a facade, often passed down through the generations. ) With this in mind, when I was younger sometimes it would be awkward when we were all seated in a common area like the hall or the dining table — a place where everyone sat at but barely spoke. Being in a shared space in silence makes you acutely aware of the objects around you and sometimes I’d finish up first so I could excuse myself from the table and walk away — not because I hate them but more of to relief myself of the disconcerting awkwardness of the situation.

However in the past few years my relationship with my family members, except for my brother has improved. We are more open about our feelings and we addressed past ‘grudges’ or mistakes that were previously swept under the carpet. Covid 19 especially amplified this — arguably in a pretty forceful way since we had no choice but to stay home. However surprisingly though I dreaded the idea at first, I was pleasantly surprised by how I ended up finding comfort in a place I always convinced myself didn’t have that much to offer (since I was mostly out all the time). It is ‘funny’ and significant how when we’re confined in an area, we somehow adapt and inherently become suddenly aware of ‘loopholes’ or ‘gaps’ we never paid attention to, that were always available to have sought comfort in.

All the common space needed was shared noise or shared conversation to rid it of the awkward stigma it had in my mind. So I started speaking more, sitting out of my room more, making a conscious effort to not only float around the house but ground myself in these shared spaces and have pleasant meaningful moments in them.

4. ‘Home’ in the House (Transition from Restraint to Comfort)

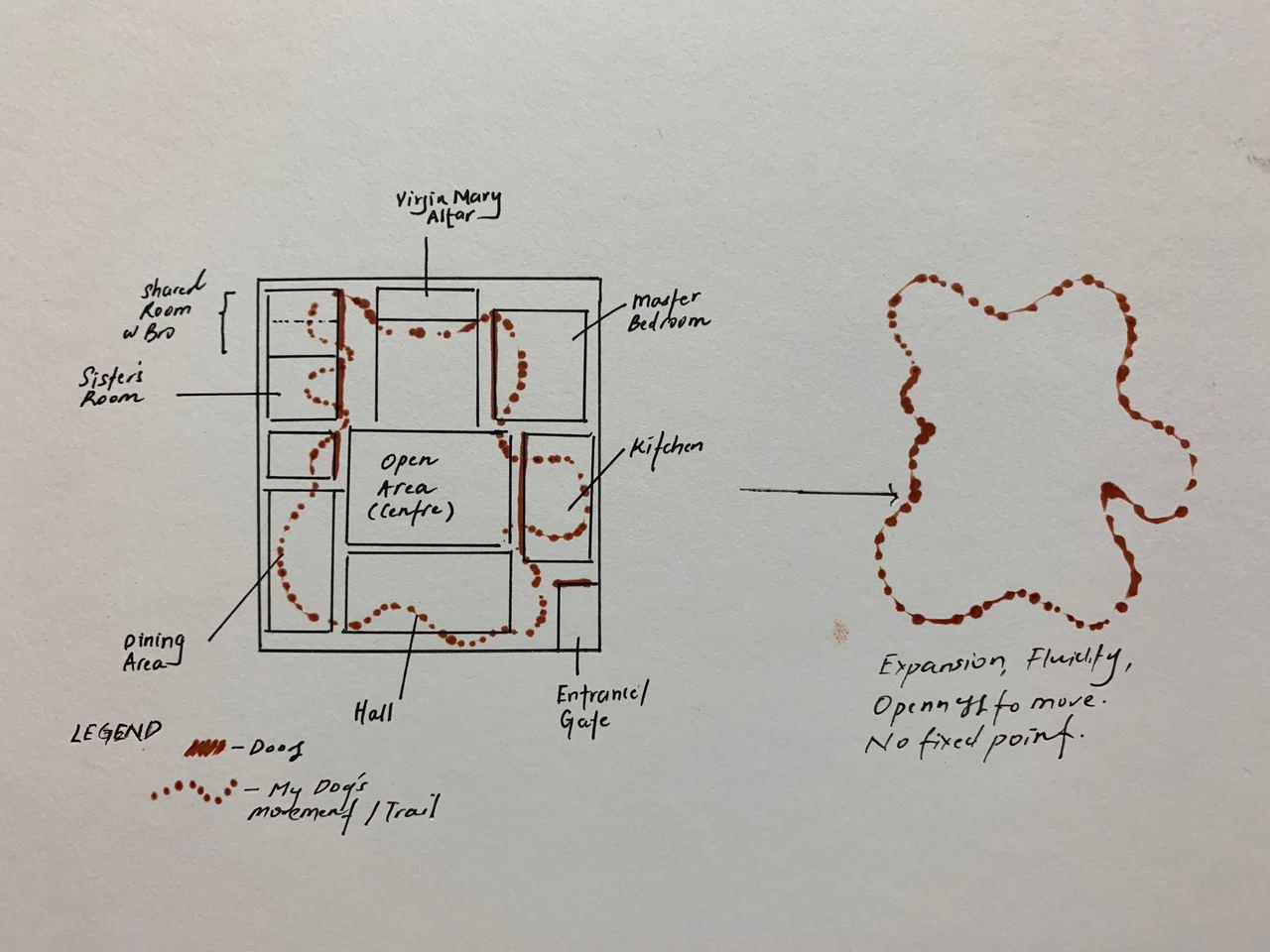

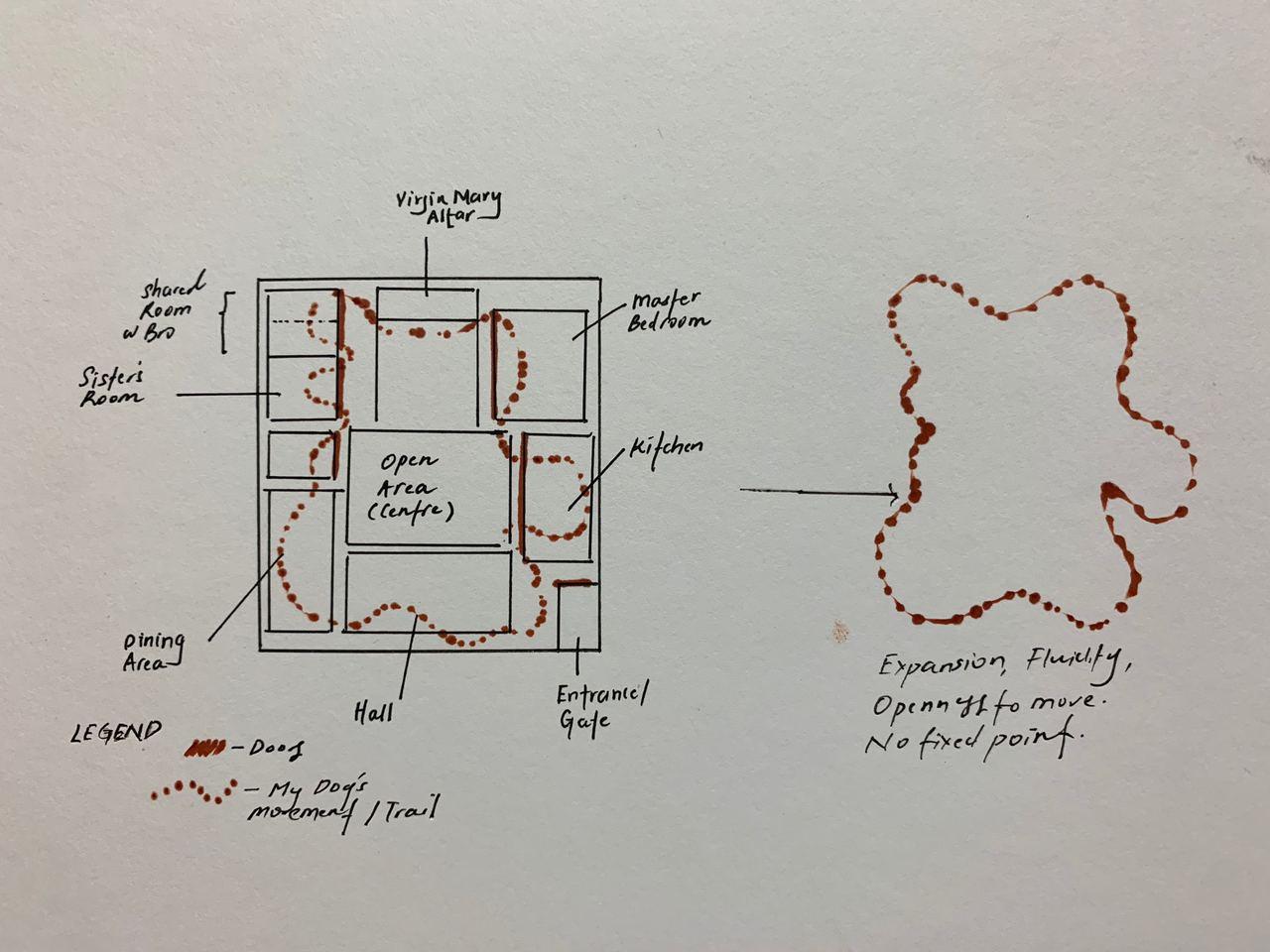

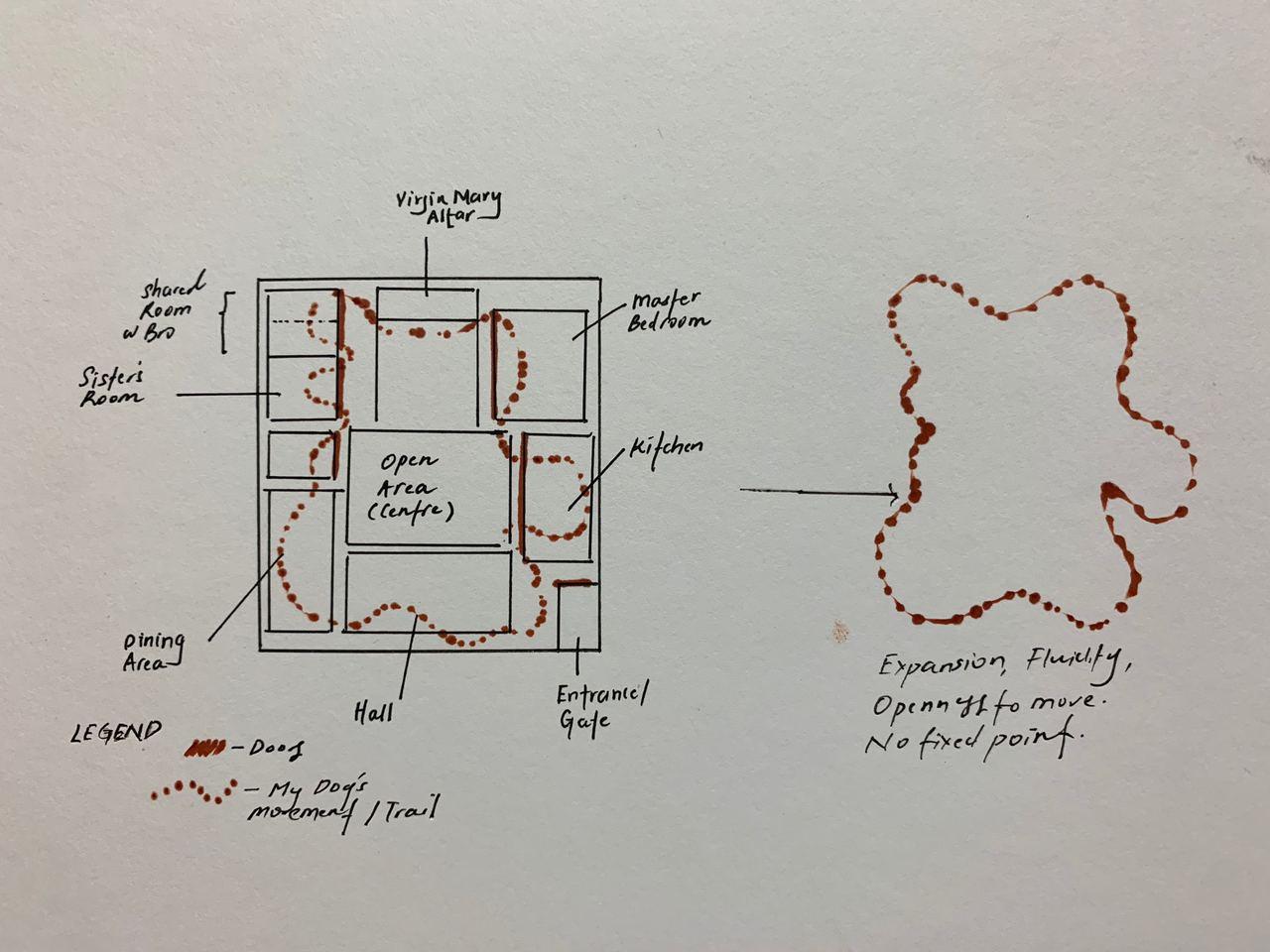

We have a corgi who is allowed to roam the house freely. And Corgis being hyperactive and needy as they are, he is always running into my room, scratching doors for them to be opened or jumping onto us ecstatically with his toy in his mouth. To him, the house is his world and he runs wherever he wants to with only one aim in mind — to interact and play with his owners. Somehow the addition of this animal ‘family’ member that ran across all our rooms, also brought as closer. We stepped out more and interacted more naturally. The artificial boundaries that we set up as humans (rooms, doors etc) were invisible to him and he freely crossed each boundary whenever he wanted to. Overtime, I too became less affected or obsessed by the boundaries of my room and started to feel comfortable in any space in the house.

The human condition is such that we are often blind to our own inhibitions until a third party intervenes. In this case, the addition of my dog and his constant running around, leaving his shedded hair everywhere, broke these spaces and in a way connected them. His physical movement overtime, created a flow in the space and amplified the openness of my ‘home’ in the ‘house’. Psychologically, he connected all the areas that were kept apart in my head. (Spaces I saw as discrete places with specific functions — to eat, to watch tv, to cook). When these boundaries broke down, a sense of openness and fluidity emerged and my physical body did not feel like it was confined, relative to the space around me, anymore.

5. ‘Home’ and ‘House’ as we Perceive it to be (Obligated Rootedness)

Space as an entity is omnipresent, it is infinite and it is not limited by the physical boundaries we have learnt to set up. This being said, whether we consider our house our home or not, we all have an obligated rootedness to this physical enclave we grow up in. For some people who grew up in an abusive household, home is a traumatic trigger, and the sight or even slightest memory of it can be distasteful. (even long after physically removing themselves from that space).

Concluding thoughts (On Homes and Houses)

For me home has grown to be a place where I am more comfortable as opposed to when I was in my formative years. Within this space, in my room due to my strained relationship with my brother, I still rely on means to establish some sort of boundary that separates me from him. Home essentially to me can be any place you feel comfortable at. You can feel at home in the most unsuspecting and unexpected of places as long as you have a personal and unique attachment to it. A House on the other hand, is a physical space we are bound by, and grow up in, whether we like it or not. Bad or good memories associated with this physical space, leaves a permanent mark, distorting or rather influencing how we eventually end up making a ‘home’ out of our own houses when we finally have the autonomy to move out and do so.

Visual Representation of ‘Home’

It is possible to alter or morph the perception of a fixed physical space by adjusting the psychological space it represents in our mind. This can be done by intervention (in my case, the simple yet powerful affect of my dog’s movement and trail).

Tokyo Train Station

Tokyo Train Station Bentley Railway Station (Hampshire)

Bentley Railway Station (Hampshire)