7 AUG 2020

NOTE: incomplete citations, will update.

i. Diagram Art

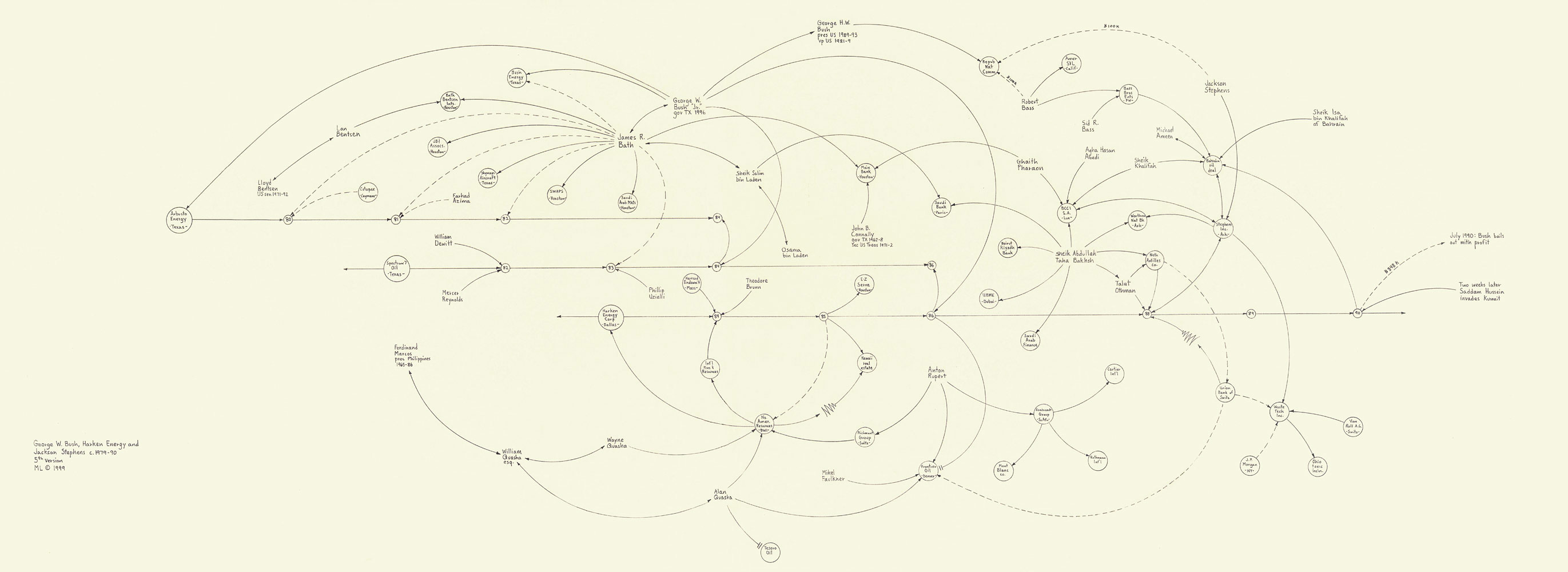

Mark Lombardi: George W. Bush, Harken Energy, and Jackson Stephens, ca. 1979-90

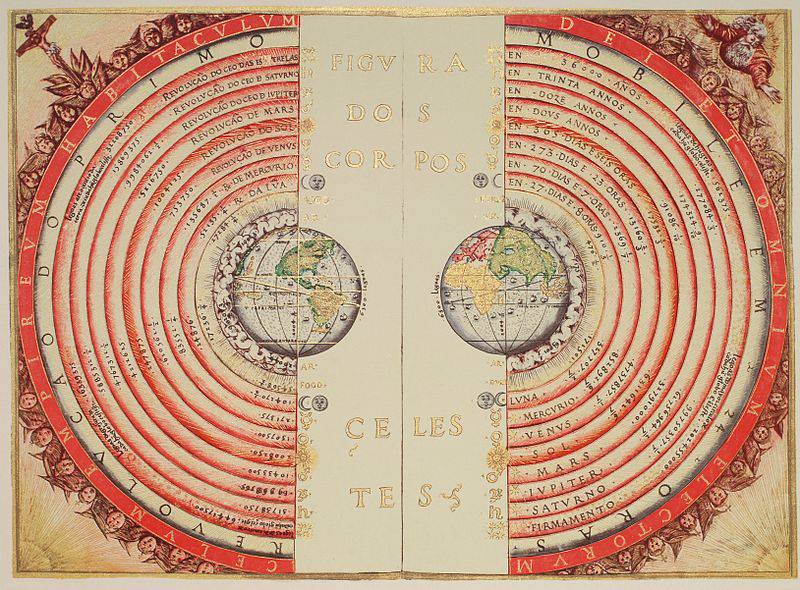

The term “Diagram Art” is not definitively a coined genre of art. Rather, it was a thought that I had conceived upon conceptualising for the art direction of Full Circle. One may colloquialism it as the genre of Infographics, but my understanding of contemporary infographics are much more graphic and abstract than I may find suitable for this project. It is of priority to ground this project in its manifesto, to chase a genre of science fiction that maximises the potential of fiction in retaining its truth value. Scientific diagrams, especially traditional ones, would be a good starting point for developing a style for this format. The intention of a scientific diagram is never to abstract the information it presents, but rather demonstrate as clearly as possible research-based concepts through a visual medium. However, while it is presented in such a manner (Fig. 1- 4), there is a clearly poetic form present within the generative amalgamation of shapes and forms used to make the readers understanding clearer. This generated visual can allow us to reach a softer, more humanistic, more poetic dimension of reading research.

Notable Diagrams

Fig. 1 The Ptolemaic System (Claudius Ptolemy, c. AD 140-150)

Bartolomeu Velbo, a cartographer and cosmographer from Portugal created this diagram to illustrate the Ptolemaic Geocentric System — ‘Figura dos Corpos Celestes’ (Four Heavenly Bodies).

Fig. 2 Lunar Eclipse (Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, 1019)

This diagram illustrates the phases of the moon. It was a concept featured in the manuscript of his Kitab al-Tafhim (Book of Instruction on the Principles of the Art of Astrology) by al-Biruni.

Fig. 3 Vitruvian Man (Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1487)

Da Vinci’s diagram of his understanding of a human’s proportions.

Fig. 4 Heliocentric Universe (Nicolaus Copernicus, 1543)

A simple diagram that demonstrates Copernicus’ theory of the Universe.

Mark Lombardi — Diagrams as Political Art

Mark Lombardi is a conceptual artist that demonstrates diagram in the form of political artworks. He uses information from public documents to create “narrative structures” that form networks in a diagrammatic form (MONEY KILLS). Unlike traditionally informational diagrams, Lombardi’s intention is political and artistic, yet it serves the purpose of informing and provoking. His conceptualist ideas are in line with the founding ideas of Sol Lewitt who believes “The idea itself, even if it is not made visual, is as much of a work of art as any finished product.”. Lombardi was also more interested in the “idea behind the creation”, rather than “the idea itself”.

His artworks are composed of lines drawn in pencil in a precise spirographic manner (Networks of Corruption: The Aesthetics of Mark Lombardi’s Relational Diagrams). They are representative of Lombardi’s research findings on the interactions between political and financial institutions, and their head figures. The political intention behind his art is to “expose” financial corruption through demonstrating “networks of transactions, spheres of influence”. Robert Hobbs’ also mentions that Lombardi’s artwork demonstrate the importance of gathering information, following the intricate research that goes into his diagrams.

Mark Lombardi, World Finance Corporation and Associates, ca. 1970-84 : Miami, Ajman, and Bogota-Caracas (Brigada 2506 : Cuban Anti-Castro Bay of Pigs Veteran) (7th version), 1999. Graphite and coloured pencil on paper, 175.58 x 213.36 cm. Courtesy of Donald Lombardi and Pierogi Gallery (Photo: John Berens).

Useful link: https://www.stevenbaris.com/diagrams-and-art

ii. Narrativising Techniques of Fictionality

The following concepts have been derived from the article “Hybrid Fictionality and Vicarious Narrative Experience” by Mari Hatavara and Jarmila Mildorf. This article focuses on narrativity in fiction and non-fiction, highlighting the signposts of fiction. It is indicated in the following headers where Hatavara and Mildorf had derived these theories.

“Fiction” and “narrative” themselves are asymmetrical in their inclusiveness: while fiction always entails narrative, narrative does not necessarily entail fiction. The process of fictionalization not only involves features of narrativization, such as the inclusion of experientiality, but it is also accompanied by a more or less gradual loss of (perceived) truthfulness. We are of course aware of the fact that in the context of postmodern theorizing it may no longer be safe to talk about, let alone assume, something like “truth” or “truthfulness.” However, while such notions may have been problematized in postmodern cultural theory, they still hold validity in other philosophical pursuits and arguably in many (most?) people’s everyday lives.

Paratextual Signals

Grishakova, Marina. “Literariness, Fictionality, and the Theory of Possible Worlds.” In Narrative, Fictionality, and Literariness: The Narrative Turn and the Study of Literary Fiction, edited by Lars-Åke Skalin, 57–76. Örebro Univ., 2008.

Hatavara and Mildorf describe “paratextual signals or context signals of fictionality” as a mind-representation technique that is used to narrate the story of a nonfictional subject. They may not be classified strictly as a “fictional” narrative, since they are based on nonfictional experiences.

“Their referential framework is still the real world and real people in it, and this is how they will be understood by listeners and readers.”

Representation of thought and consciousness

Zetterberg Gjerlevsen, Simona, and Henrik Skov Nielsen. “Distinguishing Fictionality.” In Factuality and Fictionality: Blurred Borders in Narrations of Identity, edited by Cindie Maagaard, Marianne Wolff Lundholt, and D. Schäbler. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

Two situations relating a narrative to a personal thought or consciousness were highlight in the article by Hatavara and Mildorf. They are third-person narratives that involve “internalised focalisation” or “verbs of consciousness”, and “forms which mix two discursive subjects” (Herman, David. Basic Concepts of Narrative. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.).

Dissociation of the author and the narrator

Nielsen, Henrik Skov, James Phelan, and Richard Walsh. “Ten Theses about Fictionality.” Narrative 23.1 (2015): 61–73.

Monika Fludernik’s, followed by Neal Norrick’s, described the use of third-person narration in nonfiction as “narratives of vicarious experience.” Traditionally, it had been the standard to use first-person narratives in nonfiction, as facts that have been experienced by the narrator himself, rather than descriptive of another person’s experience.

iii. Full Circle // Episodes

These episodes will be focused on building a narrative for the Moon, using only theories of scientific/research nature. Their goal is to paint a factually guided picture of the Moon, but paratextually demonstrating the philosophy and poetics behind this body of scientific study. The three episodes — “Gravity”, “Rhythm”, “Light and Darkness” — are some of the main characteristics of the Moon in relation to its relationship with Earth. These characteristics are also some of the founding principles of existence and human life. In another sense, this amalgamation of topics will personify the Moon in a ‘character’ role and vicariously communicate the narrative consciousness through this third-person ‘voice’.

(Side note: ‘Philosophy of Science’ — Science is not necessarily truth. The nature of reality may be metaphysical, and we may want to take into account the ‘actuality’ of things we observe since science cannot prove what is unobservable.)

Focus: How the Moon Keeps Us Alive

This focus has been chosen because of its familiarity and harsh factuality. It will serve as a good base to demonstrate the new narrative structure.

Expected duration of each episode: 8-12min each

Episode 1: Gravity

— Stabilising Effect

— Protection Role

— Time (Segue into next theme)

Episode 2: Rhythm

— Tides

— Seasons

— Phases (Segue into next theme)

Episode 3: Light and Darkness

— Daytime, Nighttime

— Creation and Destruction

— Lunar Eclipse

Narrative Structure

I will use Waltz with Bashir as a starting point for the narrative structure for this format. The reason for this is the debatable genre of Waltz with Bashir as it actively dabbles between the consciousness of the director and protagonist Ari Folman, interviews with nonfiction subjects recounting their war experiences, while sometimes suggesting a world of fiction and fantasy. However, there will be elements of such a narrative structure that will not fit in with the interests of Full Circle, since Waltz with Bashir has much more paratext and consciousness than scientific studies such as the Moon. Waltz with Bashir involves much more psycho-socio influences, such as trauma and amnesia, all while told through the first-person perspective of a perpetrator.

Waltz with Bashir’s story arc less steep than would a traditional story arc (Exposition – Rising Action — Climax — Falling Action — Conclusion). Rather, it takes a slow boiling approach of a steadily increasing rising action, and cathartic release at the end. The docu-animation unravels with interviews with the perpetrators as the collectively recover from traumatic amnesia, and the protagonist, Ari Folman, gains an obscured piece of information each time he talks to someone new. The big picture can only be made sense of towards the end of the film, where the audience finally understands the source of Folman’s trauma as they vicariously piece together snippets of his war memories.

Full Circle will take also be making use of interviews with ‘non-fiction’ third-person narrators’ (experts on subject), and adopt a slow-boiling unraveling narrative that ends with a ‘big picture’ conclusion. The said “episodes” and topics have already been arranged in a manner that will facilitate this narrative structure.

The Moon will take the role of what resembles a protagonist in this docu-animation, while the experts act as third-person narrators on behalf of this character. It should seem as though they are directing the narrative of the Moon. The world in which this moon will be based in should consist largely of diagrammatic elements that amalgamate to form a fantastical universe to accompany these experts’ information (but not negate its ‘truth’).—

NEXT STEPS:

Make poster of project explainer to send to interviewees

SOUND TEST:

I bought a synthesizer to create the sounds reminiscent of the examples in the previous update (Fantastic Planet, Apollo 13, etc.). The following is a test I did with my new synthesizer. The animation was done in after effects, live looped in GarageBand.