In approaching this text, I realised that one should not have a fixed definition of architecture and interior. Delving deeper into the text, one would gain a clearer understanding on the interior and exterior elements that the author as well as the featured architects, Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier, talk about in their studies of architecture.

In relation to architecture around us today, the same considerations and attention to detail that they practiced might not apply anymore. For a country like Singapore, it seems that the focus nowadays is on aesthetic, convenience and working within spatial constraints.

To be fair in comparison, houses these days are not custom built for a specific client, but rather to cater to the masses. Houses are heading towards spaces with more open concepts, giving more attention to an inclusive lifestyle that caters to everyone in the home. However, this is not to say that architects these days forgo the inhabitant’s experience completely.

Personally, one of the hardest things to do while reading this text was to detach myself from how I perceive architecture in modern times, and to look at it from a fresh perspective. This meant dividing a home in ways that was difficult to visualise, much less put it to words, and to try to grasp the concept of the philosophy. Here, architecture is read in deeper meaning; not merely a place for one to live in, and definitely not one as we know it.

Gender stereotypes in those days were definitely one of the main considerations when designing a home. In Loos’ architecture, we see the dividing of spaces in the interior as male and female, and the home as a place of security and protection. In the Moller house, Loos positioned the women’s area by the window, overlooking the interior of the home. This placement can be compared to the role of the woman in a home; guardian of the house and family. In Le Corbusier’s architecture, we see how the house was designed to cater to activities of both genders within the same place. However, the gender divide is still evident, with the female being more confined to the interior space. The progression and change in perspectives, their approaches to architecture and the human interaction with interior and exterior, seems to reflect the perception of gender equality in society. It provokes thought about the approach towards architecture in those days compared to modern times; perhaps the narratives that were told through architecture have been forgotten over the years.

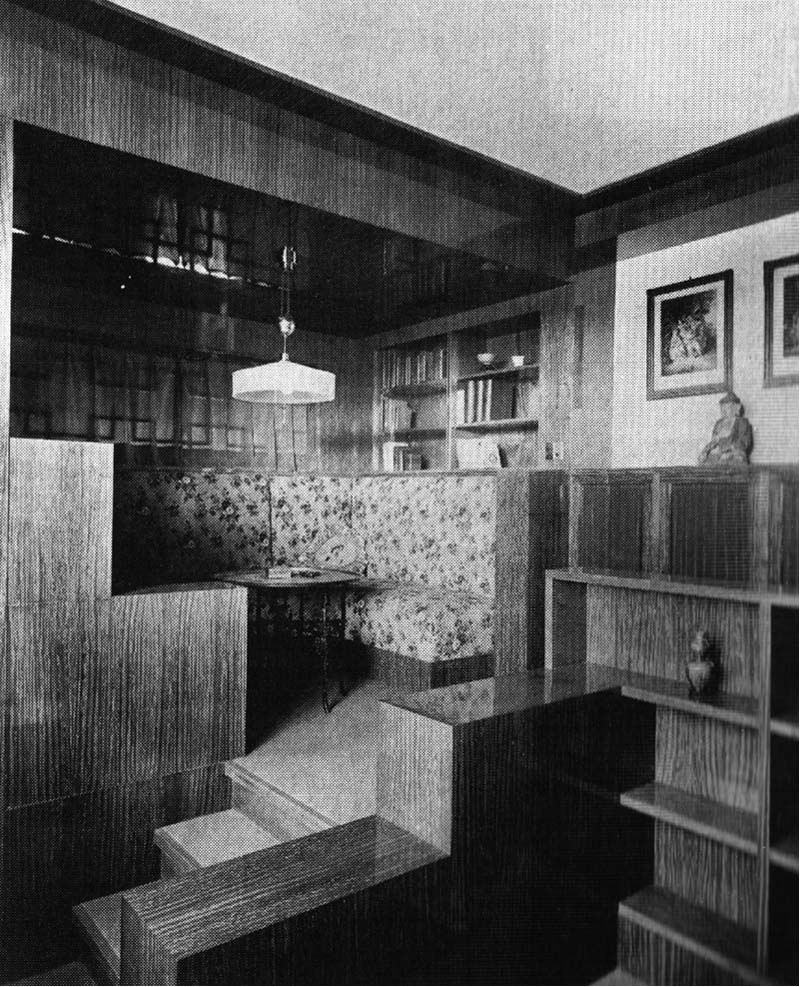

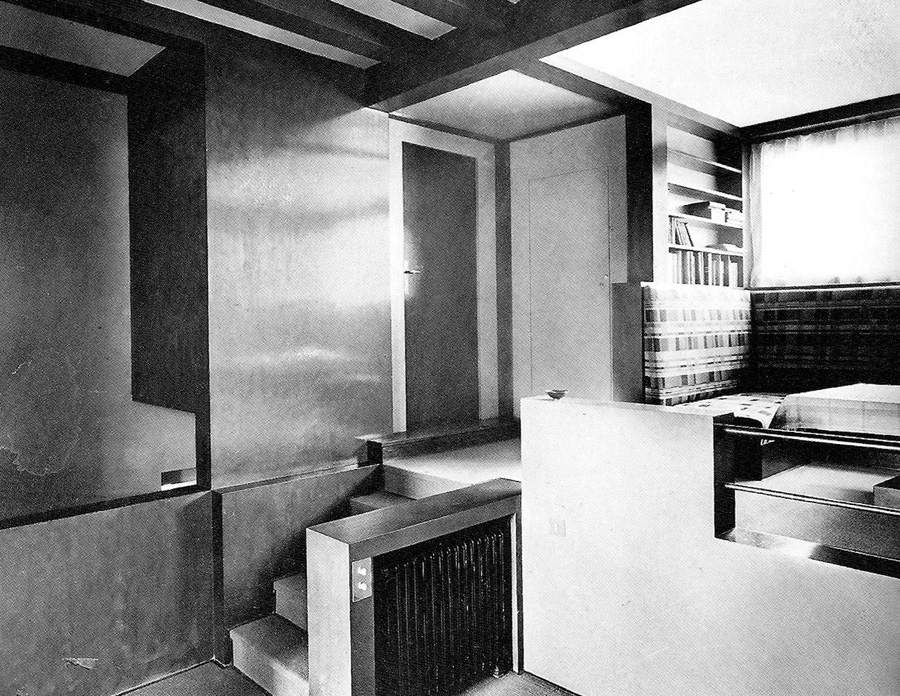

Loos approaches architecture by dividing the home by the interior and exterior, and seems to place a lot more emphasis on the interior; a personal and personalised place. This is proven in his approach, where emphasis is placed on translating the idea of a home before the structural element, prioritising the inhabitant’s personal experience. In Loos’ architecture, the window is seen as a form of lighting instead of one meant for admiring the scenery. This is an interesting perspective, where the transparency of the window is something that is not meant to be seen through, but only for light to filter through. The light from the window has a contradictory effect. It draws attention to the space, but also protects the occupant’s identity from the back light that is casted. Loos pushes the limit of interior and exterior by introducing the mirror, which shows an extended view of the home. Placed at eye level, it seems to act as a reminder to the inhabitant and to focus on the home and not on exterior affairs. In the Josephine Baker house, the window seems to function a mirror as well. It might be a metaphor for the nature of her occupation, the awareness of being seen but yet having to pretend as though the viewer does not exist. From these examples, we can see that Loos believes in designing by intuition and how he perceives one’s sense of belonging with the selected place.

L’architecture d’aujourd’hui, a film by Pierre Chenal & Le Corbusier, featuring the Villa Savoye.

Corbusier’s approach towards architecture is almost entirely opposite from Loos’, he transitions to one that embraces surroundings, marrying structure and nature. He focuses first how the house frames the view, by making use of windows and walls, before deciding on the site and sight. With the framing as priority, the orientation of the window can affect the occupant’s experience from within the home in terms of perspective and the view that one sees. In this aspect, the windows of Corbusier’s houses frame the exterior world. Corbusier firmly believes in the horizontal window as a better orientation for a home, as it is able to illuminate the space better, whereas a vertical window only provides a more holistic view. This is seen in the Villa Savoye, since the house itself is technically “lifted” off the ground, the connection to the ground was not communicated in the view as well. Corbusier seemed to want to create a more holistic experience, his architecture can be seen as a medium that grants access into a different perspective of the world. This importance on the visual experience can be witnessed in his. In his plans, he drew a landscape from a postcard, possibly with the intention of bringing it to life through architecture, by replicating the scenic view of the landscape and the way it was framed through the camera. The window blurs the line between the interior and exterior physically, yet also ties the inhabitant and his surroundings visually.

In the work of both architects, we see how they each step away from what is considered the norm when designing a home, breaking the boundaries in an experiential sense, bounded and guided by gender stereotypes in those days, while still having to consider the inhabitants’ interaction with the space. In my opinion, the window appears to be the main medium in both architects’ works. The window is the split wall, metaphorically and physically, it is “the split between the traditional humanist subject (the occupant or the architect) and the eye is the split between looking and seeing, between outside and inside, between landscape and site.”