Curatorship | Literary Review “Art out of Joint: Artists’ Activism Before and After the Cultural Turn” By Greogory Sholette

Literary Review

Gregory Sholette, “Art out of Joint: Artists’ Activism Before and After the Cultural Turn,” in The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor, edited by Andrew Ross(OR Books, 2015), pp. 64–85.

This essay, all 23 pages of it, investigates a terrain of art practice exemplified by its latter-day incarnation- the GULF project. This essay is quietly situated in the publication G.U.L.F by Scholette that focuses on artistic practices that “favour more direct political action” during the post-war “cultural turn” between 1965 and 1989. “Art out of joint” could be considered a chapter that contextualises the various forms of “direct actions” that preceded the GLC and the GULF coalition of artists and their collaborators.

Historical Lineage of Artists Activism

Through various examples of artists’ activism and their actions, Scholette unquestionably puts forth a historical lineage of post-war artists-led organised coalitions like Critical Art Ensemble, The Art Workers Coalition (AWC) and Guerilla Art Action Group (GAAG), that were active in the art world in the 1960s and 1970s. The essay sketches artists and artists collectives who respond to external events like the Vietnam War (outside of art) with their noncompliance with “research and art norms” during supposed moments of crisis. His thesis is very much about how artists as cultural producers become politically engaged, engage in social criticism outside of the formal vocabulary of art and attempted “activistic” activities to voice out against global issues throughout the periods of increased visibility and importance of art museums as cultural institutions.

In the view of Scholette, “as art and politics collude and collide with each other, panicked tradition-bound cultural institutions and artworld patrons pushed back against ..dangerous blurring of categories”. The blurring of categories between the institution and the role of the artists was highlighted in Sholette’s numerous historical examples in the essay, systematically archived in his writing from its earliest incarnation to the current day example of G.U.L.F that has come to support his argument. From the 1966 manifesto from the anarchist collective Black Mask/Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers to the Situationist International (from 1968) and their affiliation with university students, these coalitions signal a shift in how the array of ideas, organisational platforms, and “direct” political action became co-opted into practices of contemporary art.

The 1980s as a breed of tactical public interventions

Examples of boycotts by artists in protest of military and corporation involvement in Biennials by AWC or other similar coalition groups (e.g. Guerilla Art Action Group) continued into the 1970s and 1980s. In his essay, he charts how the 1980s brought together artists, writers, curators, gallerist, commercial dealers, architects and infiltrated alternative spaces in pushing forth these artists activisms beyond mere protest. The organisational competencies of these more tactical public interventions emerged, during a period of greater pragmatism, where artists and their collaborators became less “ideologically romantic”. This self-reflexivity enabled the protests campaigns to be more politically confrontational and noticed by various political and cultural leaders and the general public as well. Amplified by the mass media and “acting as public intellectuals, cultural producers demanded that national leaders, as well as museum directors, live up to democratic ideals”, Scholette in his essay lays out that through his various examples, acts of solidarity between cultural producers and human-rights groups possibly resulted in greater solidarity between populations and amplified the artists call for change.

He concludes his essay by summing up that the more contemporary examples of GLC, Liberate Tate and Occupy Museums were a clear continuum of direct actions started by the earlier waves in the 1960s and 1980s. An important difference between these 20th-century forms of protests is the “absence today of an ideological counter-narrative to capitalism, and…belief that cultural producers bring something extraordinary to the underprivileged masses via the elevated benefits of serious art”. With this premise, he has set out that contemporary art has come a long way in wielding greater power in opposition to the might of politics, institutions and the state. What is somehow lacking in his argument is primarily the effect (and affect) created by these public interventions. How much of these acts of “art out of joint” had created greater awareness of global populations which in his view are caught in the cruel cycle of precarity?

The questions that resonated

As a result of the literary review of this essay, some pertinent questions came to the fore.

- Can art and the ethics surround its creation transcend geographical boundaries in creating greater awareness of global populations caught in the cruel cycle of precarity?

- Could and Should art be politicised?

- If so, what is the aesthetic core of this activism, if it exists?

Some extended reading includes:

- Say, Jeffery and Yu Jin, Seng. (2016). Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art. Singapore: Institute of Contemporary Art, LASALLE.

- Bishop, Claire. (2012). Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso Books.

- Decter, Joshua. (2013). Art is a Problem. Austria: JRP | Ringier.

- Stimson, B. and Sholette, G. (eds.) (2007). Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945. Minneapolis, MN and London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sholette, G., & Lippard, L. (2017).Delirium and Resistance: Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism (Charnley K., Ed.). London: Pluto Press.

- http://www.gregorysholette.com/ and his other essays and videos:

- http://www.gregorysholette.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Encountering_The_Counter_Institution_Sholette_2016.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8KAopK0M-o

- http://www.gregorysholette.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/A_User_is_Haunting_the_Art_World_a_book.pdf

Protected: A Selection of Performance Art Relics (from The Artists Village, 1988 – 2008)

Curatorship | Education and Activation [A Selection of Performance Art Relics (from The Artists Company)]

A Selection of Performance Art Relics (from The Artists Company)

This exhibition presents a selection of performance art relics by The Artists Company. The selected relics were part of performances held at Your Mother Gallery from the 1st of May to the 28th of May 2018. The performance art relic is a term used for objects, which are results of the transformation from states of “mere” material to “autonomous” artworks created or used during performance art. The curated display attempts to give the performance art relic an aura beyond the connections with their situational taxonomy, “labour hours” put in and the time taken to make.

Associated Programming for A Selection of Performance Art Relics (from The Artists Company)

The programming for this exhibition consists of:

Education

- Artist and Curator Tour

- Artists Workshop

Activation

- Tour of Performance Art Spaces in Singapore

- Artwork Responses

—————————————————————————————————

Education

Artist and Curator Tour

Join a tour of the exhibition with TAC and the curator, and gain an insight into the concepts of the exhibition and processes involved in the creation and curation of Performance Art Relics.

Ticketed Event | Suitable for all ages.

Artist Workshop

How does one respond to Performance Art? What do you write about? How do you describe the experience?

In this workshop led by artist-educator Jennifer Ng, participants are invited to pen down their responses to the physical works and documentation of the performance artworks, where their responses are shared and reshaped through dialogue and re-writing.

Ticketed Event | Suitable for ages 12 to 18. Participants are required to sign up, where consent will be sought from participants on the exhibition and archiving of their written responses.

Activation

A Tour of the atmospheres and environments of the Performance Art spaces of (Chinatown and Little India), Singapore

Explore the urban spaces with TAC in this talk and tour of the locations of performance art spaces in Singapore. Using the environment of Your Mother Gallery as a starting point, learn about the spatial configurations of Performance Art spaces and re-experience the atmosphere that was generated through this guided tour by TAC.

Ticketed Event | Suitable for all ages.

Artwork Response

Explore the themes of the exhibition through a response to the exhibition by two artist-researchers:

Toh Hun Ping (Singapore)

A video artist, film research and writer, Toh has screened his video works at international film festivals and presented video installations in art venues including The Substation and Sculpture Square. Currently, Toh is researching the history of film production in Singapore and will share his archive of videos that contain scenes from Chinatown and Little India.

Koh Nguang How (Singapore)

Singapore artist and art archivist, Koh was a founding member of The Artists Village. He is a pioneering researcher and archivist of Singapore’s contemporary art history and has a focus on documenting performance artworks by The Artists Village and other Singapore artists. Currently, Koh works on his “Singapore Art Archive Project” where he assembles photographs and other forms of documentation in formats of catalogs, newspaper articles, and books in forming a narrative of Singapore art. He will be sharing his experience in documenting performance art in Singapore.

Ticketed Events | Suitable for all ages.

Curatorship | Conservation Policy (A Selection of Performance Art Relics)

A Selection of Performance Art Relics: [No. 203 (2.03 %), 3 Hours and 27 minutes].

This exhibition presents a selection of performance art relics from performances that had taken place in Your Mother Gallery, Singapore. The performance art relic is a term used for objects, which are results of the transformation from states of “mere” material to “autonomous” artworks created or used during performance art. The curated display attempts to give the performance art relic an aura beyond the connections with their situational taxonomy, “labour hours” put in and the time taken to make.

Conservation Proposal

Current Status of Object: Beech Wood Brush, Red Cotton Thread, and Human Hair.

The object was produced as part of a 3 hour and 27-minute performance artwork. The artist had bundled the human hair using red cotton thread and carefully glued them using a combination of white glue and synthetic acrylic glue within ¼ inch diameter holes in the beech wood brush. All components of the object are intact and maintained in its original state as per the performance.

Interventive: The object is currently stored in a controlled environment and does not require any (form of) intervention. There is no further need to manipulate the object.

Documentation: The object is to be labeled with its title, dimensions, material(s) and date/duration of creation. Photographs of the object from multiple angles have been taken to record the selected performance art relic.

Preventive: The object should be handled with care and not exhibited.

- The object is securely stored in an airtight and watertight enclosure.

- The object is kept in extremely low light of a value of 50 lux or less.

- The object is stored in an acid-free environment (box or otherwise), where the relative Humidity (rH) value is kept at 65.0 % or less.

Formative: The object is an organic material and improved conservation of it may be considered at a later date.

Curatorship | Exhibition Proposal (Distributed Authorship, A Selection of Performance Art Relics)

Listed Below are two proposals for potential exhibition narratives developed from the “fugitive object”.

Distributed Authorship: re-considering labour as (a form of) Art and Time (as a measure) of Currency.

This exhibition presents a series of three contemplative art objects co-authored, co-produced and co-owned by more than one hundred “artists” in a model of art production that distributed authorship over a duration of one month. The curated display is an attempt to piece together statistical representations of the labour hours put in and time taken to produce the art objects, as one reconsiders labour as (a form of) Art and Time (as a measure) of Currency.

A Selection of Performance Art Relics: [No. 203 (2.03 %), 3 Hours and 27 minutes].

This exhibition presents a selection of performance art relics from performances that had taken place in Your Mother Gallery, Singapore. The performance art relic is a term used for objects, which are results of the transformation from states of “mere” material to “autonomous” artworks created or used during performance art. The curated display attempts to give the performance art relic an aura beyond the connections with their situational taxonomy, “labour hours” put in and the time taken to make.

Curatorship | A Fugitive Object: Artwork No. 203 (2.03%)

Object Image:

Object Label:

Artwork No. 203 (2.03%) was an artwork created on the occasion of the exhibition “Got Your Name Or Not?” held on 26th of May 2018. The artwork was created as a performance art piece over a duration of 3 hours and 27 minutes by artist Ethrisha Liaw. The performance was part of the opening/closing exhibition of The Artists Company (TAC)’s participatory art project “Got Your Name Or Not? (GYNON)” held at Your Mother Gallery (YMG), Singapore.

The experimental month-long project was supported by the National Arts Council (NAC) of Singapore in exploring “Time as Currency; Labour as Art” through a “post-autonomous” project space where interaction, participation, and co-authorship took place. TAC transformed the art gallery (YMG) together with collaborators working in fields like design, research, arts management, and education into an “art factory”.

Object Biography:

Artwork No. 203 (2.03%) was created as a part of a performance art piece that spanned 3 hours and 27 minutes. The artwork was later sold on the same day during TAC’s “B.E.A.U.T.Y Auction (May 2018)” by Your Mother Gallery (YMG), Singapore.

Artist(s) Biography:

Ethrisha Liaw (b.1994, Singapore) is an artist who has exhibited locally and regionally. Formally trained in Fashion Design and Textiles, she has collaborated with artists like Amanda Heng and Jennifer Ng and co-runs her fashion label “Will & Well, a design cooperative that focuses on textile therapy for wheelchair users.

The Artists Company (TAC) is the re-imagined vision of a group of artists about precisely what a company made up of artists can and should be. Founded in 2017, TAC was started to undertake the ongoing “Got Your Name Or Not?” project. In this project, TAC aimed to work using co-operative and open-ended methods in conceptualising an art, social and research-based project that enabled “everyone to be an artist”. Working across areas of education, research, and art, TAC embarks on durational or locational projects, both creating things and things happening through their collaborative approach. Currently, TAC is working towards a publication of critical essays, photographic documentation and design interpretations of artworks as part of the “Got Your Name Or Not?” project.

Additional Information:

Artist(s): The Artists Company (TAC), Singapore and Ethrisha Liaw (b.1994, Singapore)

Title: Artwork No. 203 (2.03%)

Structure: Hand-made in singular quantity and re-traded during the exhibition auction.

Date: 26 May 2018, produced after a 3 hours and 27 minutes performance artwork

Material(s): Beech Wood Brush, Red Cotton Thread, and Human Hair

Dimension(s): W 5.0 x H 12.0 cm x D 4.5 cm

Provenance: Your Mother Gallery, Hindoo Road, Singapore

Credit Line: Private Collection of Jennifer Ng Su Yin

From the Rural to the Urban: A Place for (Public) Art in the City through The Artists Village

Hyperessay on Singapore New Media Artists | The Pioneering New Media Art of Urich Lau (Singapore)

The Pioneering New Media Art of Urich Lau (Singapore)

- Introduction

- Early New Media works and their influences

- The artist as “inverting technology” in ‘life circuit’

- Influence of ‘indeterminant visuals’ in ‘light-space’

- The Artist as Orator as a form of critique

- The Audience as Subject Matter and Material

- Art as Surveillance, surveillance as art

- Art challenges the way we look at privacy

- Does technology help us to remember or forget?

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

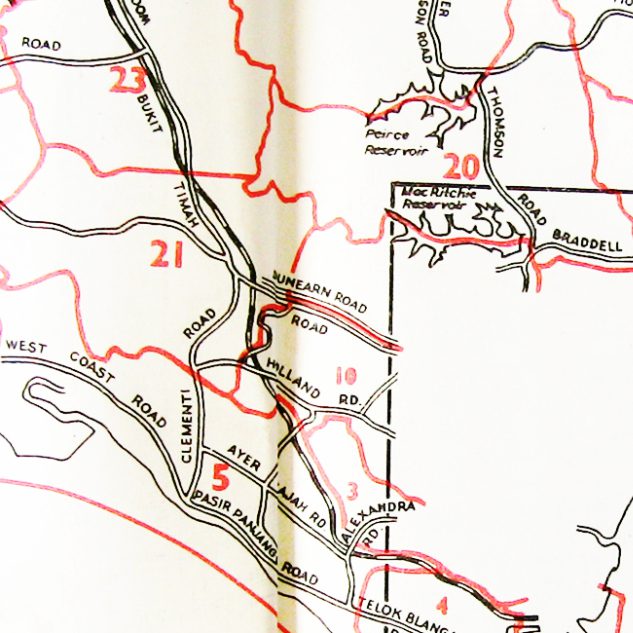

This paper explores Singapore as a city that may be small but has become a massive global tech hub in establishing itself as a highly technologised society with a labyrinthian framework of digital connectivity that connects people across the island. According to reports, the city-state comes in first for fastest connection speed and tops global connectedness indexes in terms of the distribution and outflow and inflow of goods, data, finances and even talent(s). It is this pervasiveness of technology that one assumes that this connectivity and openness to technology has infiltrated all aspects of the commercial, social and cultural aspect of Singapore. This paper discusses the work of Singapore new media artist Urich Lau as symptomatic of the conditions within the city where the artistic strategies of new media artists observe and critiques the various technological themes that face the uber-technologised ‘Smart City‘.

Historically, the art from the regions of Southeast and East Asia has been influenced by centuries of Euramerica representational painting and the western canon of art. In Singapore’s visual narrative, the development of the Nanyang School of painting is commonly referred to as the beginnings of a modern visual language in Singapore and Malaya. Such a beginning has been subsequently fractured in the past half a century as aspects of the contemporary, the performative and the technologised art has unfolded in varying levels of influence on Singapore’s visual (and art history). The resultant effect is that technologised art sits on the periphery of the visual arts ecosystem and has not infiltrated into the city’s socio-cultural conditions much. We would assume that with technology’s ubiquity in the city, there is probably no lag in witnessing the artistic practices of artists in Singapore embracing or engaging in discourses in new media art. The reality, in fact, is far from this.

This essay will explore the works of Lau in three parts. The video performance Life-Circuit (2010, 2012), collaborative video installation Light-Space (2016) and public commission The Lapse Project (2018) by his interdisciplinary collective INTER-MISSION[1].will be cited as part of an artistic strategy that engages in media art and critiques the very medium in relation to Singapore’s supposed ‘techno-culture’. The new media practice of Lau will be examined using examples from new media art history and relevant theories ranging from the writings of Roy Ascott to Randall Packer and artwork references from John Cage to Nam June Paik.

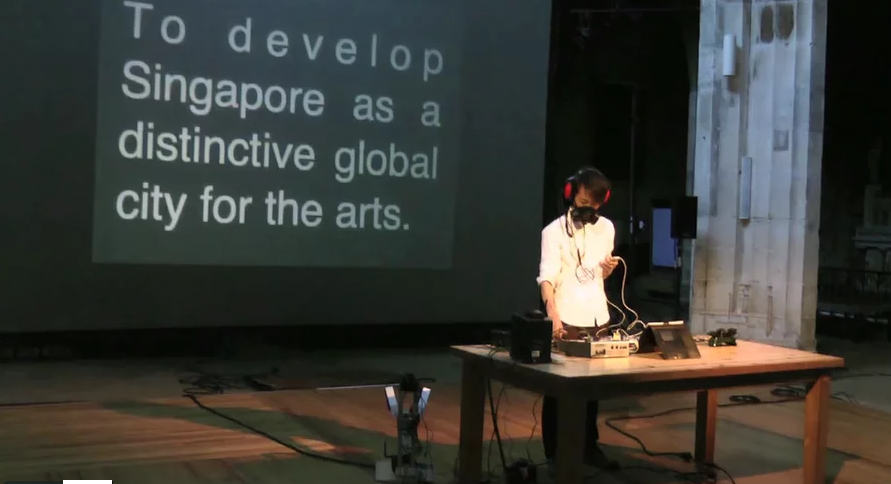

Urich Lau, Life Circuit (2012)

Saint-Merry Church, Paris, France

Part of Singapour mon amour’s performance module INTER|action

2. Early works and their influences

Urich Lau has presented works globally from across Asia, Europe, Central Asia Australasia and North America. The new media practice of Lau comprises of a visual aesthetics that is hypermedia[2] in form, in which he layers old technology with new media. In some of his earliest explorations, we see influences of Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, and Stelerac, where he explores the coalescence and construction of layers of still and moving images, punctuated by modulated sounds and set in various spatial contexts. For example, Life Circuit (2010,2012) and Video Car (2014) are examples of works that adopted the embedding of technology (or television monitors or computers) into bodies, objects, and situations. Nam June Paik’s TV Magnet (1965) is an example of an early new media artwork that influenced him; where a magnet is placed on top of the television, disrupting the television signal and hence the broadcast.

The magnetic field interferes with the television’s electronic signals, distorting the broadcast image into an abstract form that changes when the magnet is moved. Paik’s radical action undermines the seemingly inviolable power of broadcast television by transforming the TV set into a sculpture, one whose moving image is created by chance procedures and can be manipulated at will. Through his transformation of the television image, Paik challenged the notion of the art object as a self-contained entity and established a process of instant feedback, in which the viewer’s actions have a direct effect on the form and meaning of the work. The interactive quality of Magnet TV paralleled the audience involvement essential to performance art and Happenings of the early 1960s, and also anticipated the participatory nature of much contemporary art. – Whitney Museum of American Art

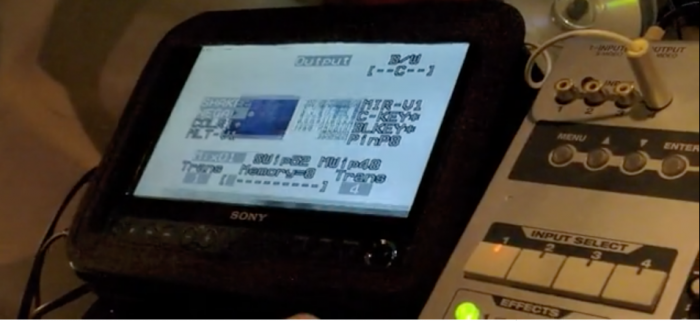

Video Car (2014)

Lau’s Video Car (2014) and Life Circuit (2010, 2012) have visual semblances to the Paik’s artistic oeuvre, where television screens and its latter-day incarnation of the digital projection are employed by Lau in various forms, from a performative installation that broadcasts images from tv monitors to a sculptural video piece as in the case of Video Car. The moving images created in both works as well as later works like Light-Space (2016), are not clear unmodulated digital signals but signals that are distorting forming abstract forms that change when audience moves or lighting conditions changes.

Lau’s work is challenging not just the notion of an art object but also a critique of the culture in which it is made in. For example, Lau’s Video Car is positioned in one of Singapore’s most highly attended public art event ‘Night Festival’ where the general public is treated to live performances of music, theatre and performance art. Lau has intruded into the cordoned off streets and transformed a car into a new media sculpture where a TV set plays random imagery manipulated at will by the artist or guest video-jockey. This radical gesture resulted in confused and curious on-lookers who took to documenting such a rare and dichotomous sight.

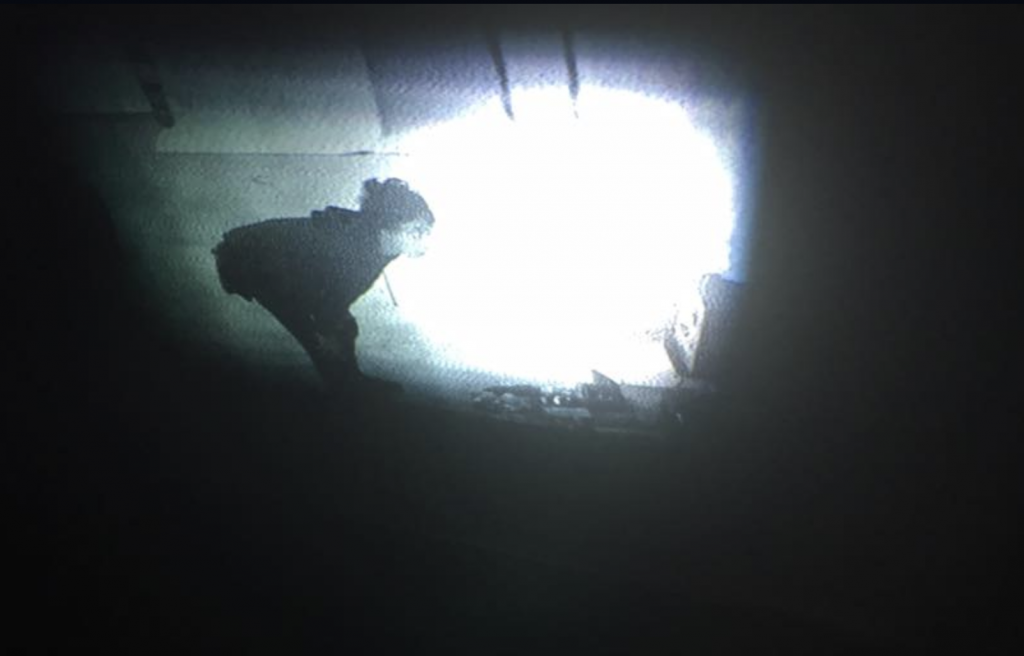

Life Circuit (2010, 2012)

Life Circuit (2010, 2012) takes on a more performative and bodily form. Akin to Paik’s controversial performance pieces like Opera Sextronique (1967) and TV For Living Bra (1969), where he includes smaller television sculptures on human bodies, robotic devices and giant video walls with synthesized imagery pulsating from cathode-ray televisions, Lau has devised an electronic media performance piece that is ground-breaking in technology and new media-savvy Singapore. Lau can be said to mischievously embrace the ‘technologies of a technologised society’ in producing Life Circuit (2010, 2012) and re-performing it locally in museums, art schools, independent art spaces and abroad in biennales and expositions (in Paris, France). The work is ground-breaking in forming a connection between observer, the ‘collaborator’ and the viewing publics as well.

In the various iterations of Lau’s video performances, he dons wearable gadgets reconstructed from industrial safety equipment like a gas mask and welding goggles in presenting a ‘hybrid-being’ in disguise. His works are akin to Ivan Sutherland’s Head-Mounted Display (1969) and Michael Naimark’s Aspen Movie Map (1978) where the artists subsumed technology as bodily art-appendages. Similar to Naimark’s Movie Map, there is ‘travel’ involved in the work, where the collaborator walks around the museum space in a “surrogate travel”, in which the artist (unlike Aspen Movie Map, where it is the viewer who is transported virtually to another place) views the spaces the collaborator is walking around in. At the same time, the projected images are also a re-creation of these visuals with pre-programmed visuals authored and sequenced by the artist in-situ. The real-time experience of the work is one that is unique to the audience witnessing the work in the projection space. Life Circuit (2010, 2012) is thus similar to Naimark’s Aspen Movie Map (1978) in integrating the movement of people around the space into a projected imagery- almost like being brought on a tour of the space.

3. The artist as ‘Inverting Technology’ in Life Circuit (2010, 2012)

Not just content with referencing examples from new media art histories, Lau’s video performances can be seen as inverting the capabilities of these technologies and critiquing our society’s adoption of innovations. His performances call upon the gadgets to become the extensions of the artists. These examples of technology impede him- herein blocking, instead of giving the artist the capability to navigate or visualise new spaces. The artist is now barricaded from his visual, audible and vocal capabilities and is only a vessel/machine in projecting out video and audio streamed from life-feed and playback media to the audience.

In the artist’s interview[3], he shared that in Life Circuit (2010, 2012) and other similar works- his intention was to form a ‘circuit’ between the audience, the medium and ‘let the moving images and sounds produced from these interactions replace (his) human senses in perception and expressions’. It is in this series of ‘life-circuit’ works that Lau has deftly inverted technology by producing situations of inconvenience and its impediment in questioned our society’s embrace of technology. Further to this, he body of works questions if there’s a need to be more careful in picking the technology to adopt.

4. Investigating the artists and indeterminant visuals

With these examples, we are introduced to a Singaporean artist who has embraced technology but also mirrored the deficiencies inherent in an over-dependence on them. Next, we continue our investigation of new media history in assessing how Lau has staged events within a technologically-mediated visual framework.

The works of Lau largely depends on the interaction between audience- with indeterminant visuals created on TV and projection screens in real time and pre-programmed. The images are at times abstract, fractured and moving-image representation with moments of intermittent flash (caused by camera lens flare). These images are sometimes a result of live feeds and embody an element of ‘glitch art’. The glitchy nature of the images are mainly due to the technical glitches brought about by interference from various sound, visual and computation equipment. We can observe that the various iterations of Life Circuit (2010, 2012) highlights the fallacy of such interactivity and places the artists’ body as an altered being that forms the ‘somewhat forced’ connection with technology and the audience.

“What is projected into the physical space are what the cables in and out of the body of this part-machine and part-man has achieved- a performance sequence that is a result of the presence of the audience, where capturing people in the images has distorted the sound due to the video/sound mixer interfering with the visuals.”

Urich Lau

As can be seen in the earlier works, Lau’s work very much depends on the reaction or presence of the audience and touches on ideas of indeterminacy. He has been influenced by cinema, music and as a result his work deals with the inherent indeterminate relationship between music, images and the audience. A characteristic of hypermedia artwork is ‘the shift away from the traditional art audience passively observing’, critiquing and historicising the artwork. Here is a hypermedia artwork that is mediated through multiple media(s) and produces limitless possible associations between previously unrelated mediums.

4. Influence of ‘indeterminant visuals’ in ‘Light-Space’

In Lau’s work as well as other new media pioneers like John Cage, Nam June Paik and Rauschenberg- “the structures of ideas are not sequential” because the audience takes on a participatory role instead of one of passivity and is required to create meaning together with the artists and the medium (in this case technology). The unpredictability of the images formed from the live-feed is akin to John Cage’s Variations V (1964) and Rauschenberg’s Soundings (1968) where motion and sound are used as triggers to control imagery, performance and the experience in and of the space.

John Cage is perhaps one of the most influential avant-garde composers and artists of the 20th century, and with Variations V (1964) has used chance techniques to create an unpredictable, indeterminate relationship between music, dance, and image. Where a sensor tracks the motion of dancers and this movement is then used as a control source for the sound input. This together with Soundings (1968), where it is an interactive media work that draws vocal sounds of the audience to activate lights from within the sculpture; which will then light up the chairs, presents an entirely new role for the viewer. Rather than being a passive observer or receiver of the artwork, the viewer is now empowered to actively shape and affect the imagery and their experience of the work with their input or voices.

Therefore in Lau’s work, as in the case of the experiences of Life Circuit as well as Light-Space, the audience becomes an activator of images and experiences for the space. For example in Life Circuit, the imposing pre-programmed text and images, as well as the electronically filtered elements found within the audience and the exhibition space, created a poetic experience of interactivity between the artists, the audience’s physical presence, and the dull lull of the electronic gadgets. As is the case in Light-Space, the visitor’s movement results in changes in the images projected in the exact space that the audience walks, talks and resides in. This embodied experience projected and articulated by Lau is an example of his artistic strategy of engaging in the discourses of new media art. Unlike other local artistic practices- he not only engages in new media art, he is also producing a form of art that is apart from other art practices experienced in Singapore- where he deftly critiques at the same time ‘aestheticises’ the experience.

5. Artist as Orator as a form of critique

So far we have touched on how Life Circuit attempts to form a ‘circuit’ between audience, art medium and moving images. As a form of social critique, the work also touches on issues pertaining to the state of contemporary art and heritage in Singapore’s context. For example, in an iteration of the work abroad like Malaysia, Taiwan and in the Pyeongchang Biennale, Lau included ‘statements as noise’ and programmed computer voices to read out the National Art Council (NAC)’s mission statement. With this radical gesture, he has presented himself as an ‘orator’ talking about the conditions of Singapore Art to the foreign and unsuspecting audience. In Lau’s work, there are elements of ‘entropy’ being forewarned to the audience. As the avoidance of entropy is seen as a response(s) to feedback, the interactive nature of Life Circuit calls on the audience to exchange or communicate information between the user and the machine (in this case the artist-hybrid-being) through action, gestures or sound.

The artist as orator and presence in these performative video works can be seen/read as reading out set ideals from the nation body/institution for the arts in Singapore. I see the inclusion of the text as a gesture by Lau to push his audience to reflect upon the mandated aims set out like a manifesto for the arts in Singapore. In essence, the performance-video piece Life Circuit (2010, 2012) can be read as an entropic treatise on the possible development of Singapore into a mega-corporation, where the quote below from Cherian George’s controversial book can be a basis for Lau’s investigation into the fabrics of our society.

Singapore’s tragedy is not the absence of idealism, but that it systematically rewards the individualistic majority and discourages the socially-conscious minority…. the overwhelming ethos is to mind your own business. Singapore’s embrace of the market forces … has provided rich incentives for Singaporeans to work hard, and to create wealth. But its exercise of illiberal controls to maintain ownership of the public sphere adds up to a heavy tax on thinking socially and acting politically. The public has been privatised.

Cherian George, P.202 (Singapore The Air-conditioned Nation: Essays on the politics of comfort and control 1990 – 2000)

As reference in Cherian George’s critical anthology of writings about Singapore, Lau’s work can be read as highlighting the symbiotic relationship between the artists and the purveyor and guardian of the arts in Singapore- the NAC, just as the orator speaks in a mechanical voice, sequences of glitches inevitably disrupts and interrupts the reading of these lofty messages. So who is the audience here, are there mere participants or are they the purveyors of this greater chance?

6. Audience as Subject Matter and Material

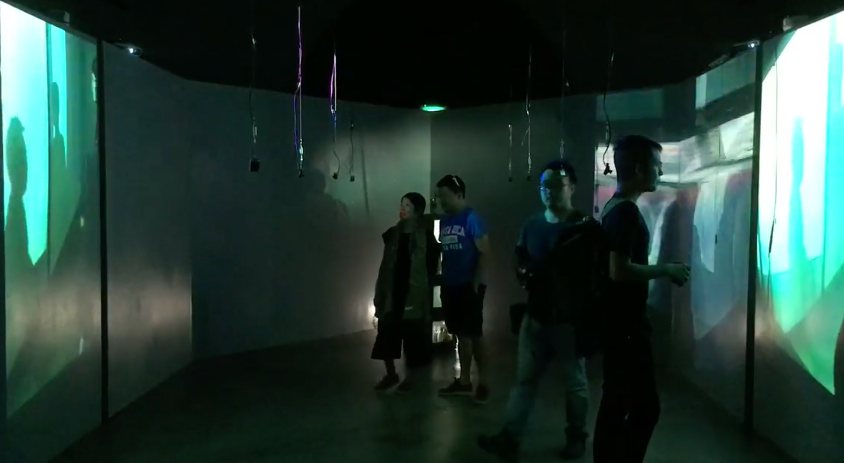

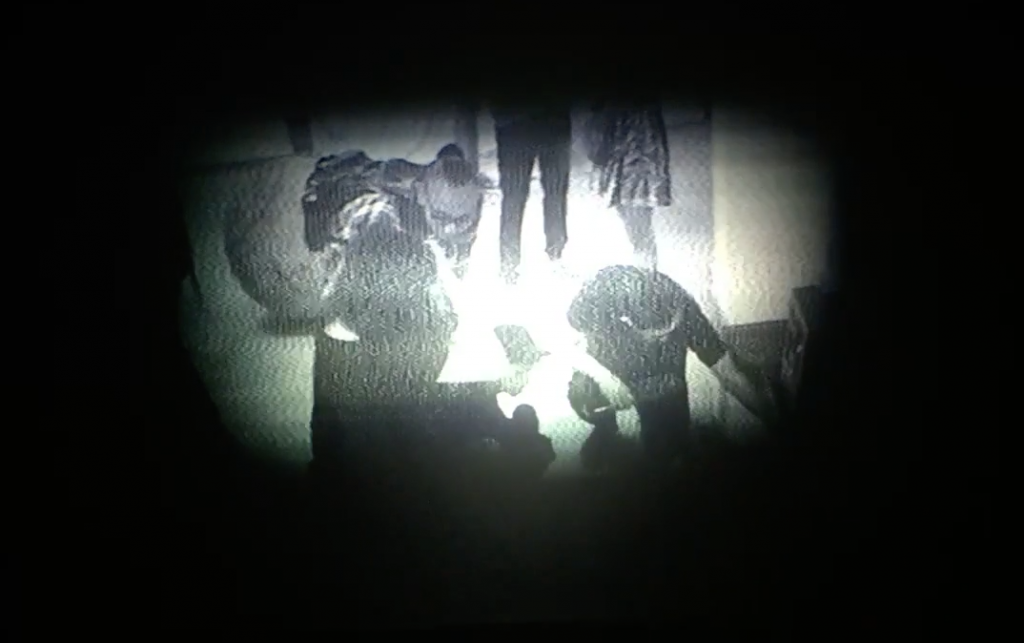

Speculations aside, on top of calling on the audience to exchange and communicate with his art, Lau extends the ideas manifested in iterations of Life-Circuit to the collaborative site-specific work Light-Space (2016). On multiple levels, this work requires close examination as it contains a layering of ideas that Lau has constantly engaged in his artistic oeuvre, wherein this work issues of surveillance, viewer-participation (or non-participation in Singapore’s art scene) and fetishism of the moving image are explored.

Light-Space (2016)

Light-Space (2016) is a multi-media installation between two unlikely collaborators- a painter of the traditional medium and a new media artist-technocrat. How do the practices of these two artists who engage in mediums separated by years of technology and discourses come together to enact a site-specific artwork?

The unique collaboration birthed an artwork that placed the audience as subject matter (and material), for without the audience the artwork ‘will just be lights in space’. Space itself is the vessel to allow the content to flow in, out and around. When people entered the space, the place becomes activated, and images/sound is formed. With this activation of the space, much like other immersive new media works like Variation V (1964) and Soundings (1968); materiality is birthed from the coalescing of matter (moving audience) and light (camera lens flare and moving imagery). The interaction of captured images (formed from movement by visitors to the space) and electronic pulses animates the colour, forms fragmented moving shades of light and create an aural soundtrack for the space. The sound in this case is formed by the feedback created by moving bodily forms and is akin to John Cage’s Variation V (1964) where the movement becomes a trigger and controller for ambient sounds.

Similar to Life-Circuit, the absence of images is echoed in the work, where images can only be formed if there is an audience. This “content-less” nature of the art can only be formed when the live feed from surveillance cameras in the space picks up movement and feeds them to the projectors which will then project onto the walls made of silver panels and form imagery that appeal painterly and ephemeral. This radical gesture is almost a reference to the hollowness felt by the spectator/artist and society in the experience of the arts in the city-state. In not reading too much into the visual void, I asked Lau in the interview: So what does the audience see? He answers:

The feedback of lights when they walk in, then the audience reacts to the work and sees fragments of themselves, their reflections. And when no one is in the room, the lights swing and captures reflections.

Urich Lau

Author’s reflection on the work

Those reflections in the empty spaces were beautiful moments in the work, I almost wish that the audience never appears as the abstract images formed by wedges of colours set against stark bright sparks (due to camera lens flare) envelops the space in a contemplative echo. There is beauty in that void. More poignantly, the gallery sitter is viewing the empty room, from a space behind.

Behavior becomes art, and the simplicity of the idea creates an experience that is the confluence of painterly aesthetics and technological inquisition.

Urich Lau, Light-Space (2016) Exhibition: Objectifs – Centre for Photography and Film 2 to 22 Dec 2016

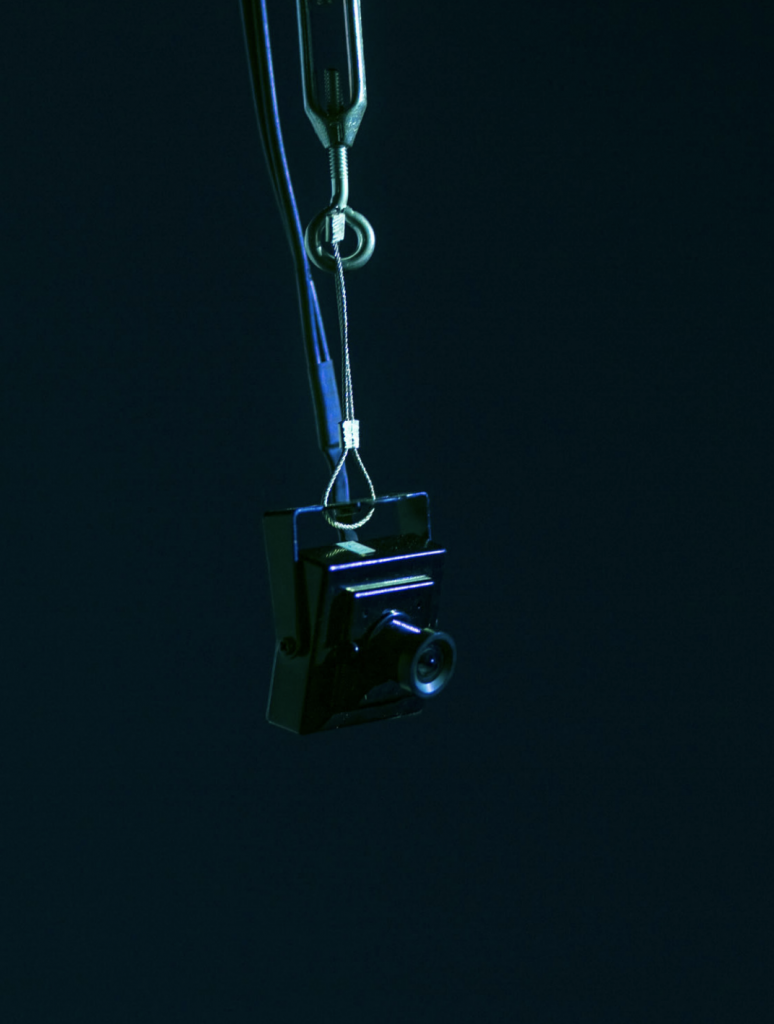

7. Art as Surveillance, surveillance as art

In charting the artistic oeuvre of Lau, surveillance of oneself and the surveillance of one’s society as one of the strong themes in his works. In ‘Light-Space’, the audience is given the (false) possibility of being given freedom to roam, but the surveillance camera is always there. Unsuspecting to the audience, another person sits behind the wooden frames and is observing them. Lau has cleverly constructed the space to bring up contentious ideas of surveillance, freedom and the ubiquity of technology controlling or ‘data-fying’ our lives.

In this work, Lau once again presents an immersive video-installation that calls upon technologies from sound-devices, video-splicing software and surveillance cameras to critique our contemporary world- or specifically contemporary Singapore. Lau specifically mentioned:

And in some sense when people enter the space it’s going to be disorienting with the images, the tunnel and the sound coming in. So, I’m wondering, this whole concept of disorienting the audience coming into the space, subverting their expectation of what an exhibition is supposed to be, what a space, an exhibition space is to be…

Urich Lau

This sense of disorientation is achieved with the dangling of multiple surveillance cameras that uses live feed to produce an immediate projection of the figures in the space.

At the same time, Lau is making a statement about what an exhibition space can be and is supposed to be- a white cube to experience an artwork passively. On a socio-cultural level, Lau is questioning the abundance of data and technology around us- just as his visitors are encouraged to take photos of the space, the people and the reflections or all of their experiences.

8. Art challenges the way we look at privacy

He sets up this scenario to challenge the way we look at privacy, especially poignant due to the currencies of our contemporary world. He shared that he encouraged audience participation and pushing the interaction to a post-digital domain, where the photographs were taken and posted on Instagram- where they may then circulate back to become a data or content on the internet. In Singapore, we are a city besieged by technology, to a level that is overwhelming. This large-scale video installation cleverly (and somewhat subtly) brings up questions of our culture- where we are asked:

- Why do we produce images?

- Why do we photograph or film life events? What do we do with them?

- Will it (the images) come back to haunt us?

Who’s watching and who is being watched?

Light-Space (2016) thus operates as a thought-provoking artwork on various levels and through the deft use of technology has constructed a scenario that brings to mind Roy Ascott, who wrote on the historical roots of new media:

meaning is not something created by the artist, distributed through the network, and received by the observer. Meaning is the product of interaction between the observer and the system, the content of which is in a state of flux, of endless change and transformation.

Roy Ascott

Lau through the examples of these rarely seen new media artworks have played with the language of video art, installation, sound art and broken them down and re-assimilated them in the space all at once, almost creating an endless change and transformation. The employment of disruptive and ‘content-less’ images coupled with the restructured space produced a somewhat disorientating but poetic work that looks at the condition of the site and presents a self-reflective space to contemplate on Singapore’s condition of the arts.

9. Does technology help us to remember or forget?

In ending off this essay, we will look at an artwork to be shown in April/May (26th April to 12 May 2018) by INTER-MISSION- a collaborative art of Urich’s creative mind. The Lapse Project (2018) is a collaborative new media artwork that presents experiences for the visitor who will toggle between the physical and the imaginary through the use of VR headsets, viewing of ‘panorama-lapses’ on large-scale projection videos and particle lapses (through live sound feeds) while walking through The Artshouse[4]. All of these experiences are set in The Artshouse, a national monument in itself where the visitors will develop new visions and modes of interaction with Singapore the city, and question one’s relationship to these monuments, and what constitutes one’s collective reality’.

In interviewing Lau, he shared that he was pleasantly surprised when NAC and the organisers selected their proposed work for the Singapore International Festival of Arts (2018). INTER-MISSION had proposed a radical idea of an interface that enables places of artistic and cultural importance to be editable and more contentiously switched on or off- almost like removing them from our memory. He highlighted that he was certain that the state-sanctioned council will not see too kindly to removing one’s cultural sites, let alone remove four of Singapore’s oldest buildings that now serve as spaces for the arts around Singapore’s Civic District.

INTER-MISSION The Lapse Project (2018)

Singapore International Festival of Arts (SIFA) held at The Artshouse, Singapore

The project was accepted and Lapse Project (2018) will be created. The work takes on a multi-dimensional and interdisciplinary approach to art-making which is a reference to the artistic strategies of Lau. The Lapse Project seeks to question the use of space in Singapore, the lapses in memory in Singaporeans and the possible effects of these physical lapses on national history and national culture.

10. Conclusion

We conclude that with The Lapse Project (2018), it has come to embody the ideas in Life-Circuit and Light-Space and more. The piece picks up from Lau’s artistic strategies in positing visitors as active participants, where in this case they contemplate on the presence and absence of the arts in Singapore (through the physical removal of these art institutions). Similar to the two works presented earlier, the yet to be experienced work employs Lau’s vision of inverting technology to question one’s own being and place in time and space. Looking beyond the artist and at the system of art viewership and reception in Singapore, The impending materialisation of The Lapse Project can be considered an indication of an increased acceptance or appreciation of new media art in Singapore. Lau and his collaborative outfit INTER-MISSION is an example of a collaborative artistic endeavour that adeptly use(s) new media to bring to fruition their aesthetic visions and thematic concerns. As a result, the work can open up further debates and dialogues about national identity and uses of our city-space. It is also through this lengthy and timely survey of Lau’s artistic strategies that we are able to glean the strong messages about our society that resonate in Lau’s poignant new media artworks. Here is a new media artist who addresses technological themes in a manner unlike any other in the cityscape, and it is my intent in writing this essay that Ulrich Lau is situated as an important critic and pioneer in Singapore’s early new media art history.

Bibliography

- Randall Packer and Ken Jordan, Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality, 2001

- George, Cherian, Singapore The Air-Conditioned Nation: Essays on the politics of comfort and control 1990 – 2000, 2000,

Websites

[1] INTER–MISSION is an art collective focusing on interdisciplinary and collaborative works in video art, audiovisual, performance, installation and interactive art, and discourses of technology in art.

[2] Hypermedia is defined (by Parker and Jordan 2001) as the connections between different discrete media elements that provide a personal trail of association among them

[3] Interview with Urich Lau conducted on 12 April 2018, NAFA Gallery

[4] Occupying the almost 200-year-old building that was home to Singapore’s first parliament, The Arts House plays a key role in the country’s arts and creative scene. The Arts House is an interdisciplinary art spacer that promotes and presents multidisciplinary programmes and festivals within its space.

Hyperessay Research | Urich Lau’s Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016)

Not lagging, just interactivity in the art.

“Traditional narratives are being restructured. As a result, people feel a greater need to personally participate in the discovery of values that affect and order their lives, to dissolve the division that separates them from control, freedom… ” – Lynn Hershman

Using Hershman’s prescient quote to delve into the multimedia artwork by Urich Lau Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016), we are introduced to a multi-media work that transcends spaces in restructuring traditional narratives. One’s foray into an art exhibition brings forth a personal journey of viewing an artwork in-situ, where the narratives are played out exclusively in the gallery space. The existence of surveillance cameras persists as fixtures ever-present and immovable in the formal spaces of a gallery. Unknowing to the visitor, Lau’s work plays on this notion of surveillance via these ubiquitous devices to present an artwork that prompts interactivity.

Interactivity

For this particular work, Lau’s video installation experiments, rather poetically, with ideas of interactivity, surveillance and somewhat subversively sharing of data (or privacy). The work operates on two distinct spaces- that of the internet (cyber-space) and the physical (gallery-space). During the period of the art exhibition, the work invites viewers to access via the Ustream app an opportunity to watch or simply gaze at live feeds of the exhibiting space. The app consequently also allows for viewers to provide live feeds of other art spaces they are visiting or even their selfies. Simultaneously this feed is projected in the physical-space of the art gallery, conflating a sense of space with an image of the present space and interspersed with images of another space.

The emerging new order of art is that of interactivity, of “dispersed authorship”, the canon is one of contingency and uncertainty. What is meant by dispersed or distributed authorship? …Thus, at the interface to telematics systems, content is created rather than received. – Randall Packer

In Lau’s work, a sense of uncertainty and contingency is exacerbated via a viewing of the video images, interspersed with glitch, error and intentionally ‘lo-fi’ in the darkened space. The visitors not only emerge as forming the visuals in the work (visually) but also have the power/propensity to take on part of the “dispersed authorship” generously provided or facilitated by the artist. In Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016) the interface provided by the artist is one of a “poetic embrace of noise and error” as exemplified by the writings and artworks of John Cates. Referencing Cates, we embrace the idea of ‘sharing and tagging one’s activities and whereabouts’ as an interfacing with the work and the gallery space. No doubt, in this techno-social culture, we see an artist like Lau enabling art that is socially performed and poetically embracing ‘random or chance’ performative moments.

Immersion

“The human mind… operates by association,”

Vannevar Bush

At the same time, this work opens up questions and issues related to information sharing and online/internet privacy. As aptly put by Bush, when one sees an interior of a gallery, the immediate reaction would be to relate and associate it with the space they are in. By enabling visitors during and after viewing the exhibit to provide input and co-author the viewing of spaces by others, the immersive space becomes operated by many and not just the author (or artist). With this interactivity, questions of online surveillance and the phenomenon of “checking-in” and “checking-out” of locations using geo-tagging methods are put forth to the visitor and one is left with an artwork that is an open-system in exploring these possibilities and constraints. The immersed visitor can author images while viewing the work in the physical-space or proceed to doing so off-site or at a later time and space, causing an interruption to the installation set-up.

Interruption

Alternating between spaces interrupts one’s viewing of the work and the live-feeds of images and happenings from other art-spaces or for that matter private spaces highlights how we are in a modulated world where our windows are constantly stacked, closed and duplicated.

“It is my belief that computer and media technology will continue to have an increasingly profound effect on everyone on the planet… and if artists don’t jump in and proactively help shape these powerful new tools, it will be left by default to advertisers, the military, organized religion, and sex peddlers.” – Michael Naimark

With Naimark’s quote, we are reminded of the recent development in the invasion of privacy (by major technology corporations) and proliferation of fake news. On many levels, the piece by Lau is an example, albeit a small one of the potential technology (via web-based apps) where a conflation of space can control, manipulate and have a profound impact of peoples experience of art and the world at large. Will we one day ask: The video images lag but is it just interactivity in art?

Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016) Urich Lau. Exhibition: Survey: Space, Sharing, Haunting Curated by Post-Museum The Substation 1 – 30 September 2016