Not lagging, just interactivity in the art.

“Traditional narratives are being restructured. As a result, people feel a greater need to personally participate in the discovery of values that affect and order their lives, to dissolve the division that separates them from control, freedom… ” – Lynn Hershman

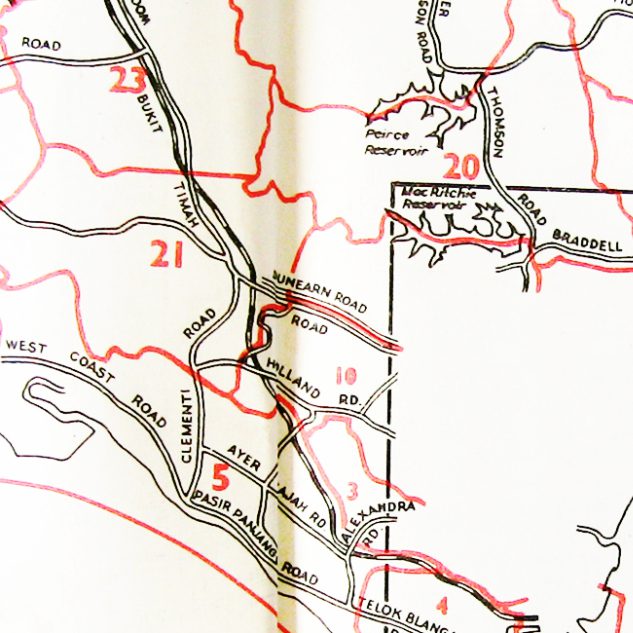

Using Hershman’s prescient quote to delve into the multimedia artwork by Urich Lau Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016), we are introduced to a multi-media work that transcends spaces in restructuring traditional narratives. One’s foray into an art exhibition brings forth a personal journey of viewing an artwork in-situ, where the narratives are played out exclusively in the gallery space. The existence of surveillance cameras persists as fixtures ever-present and immovable in the formal spaces of a gallery. Unknowing to the visitor, Lau’s work plays on this notion of surveillance via these ubiquitous devices to present an artwork that prompts interactivity.

Interactivity

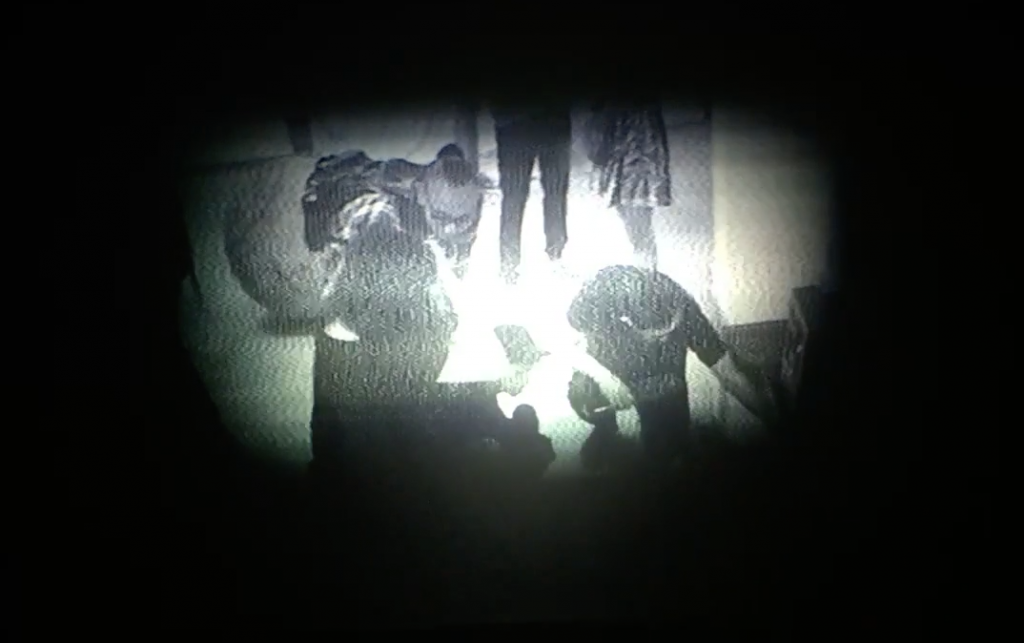

For this particular work, Lau’s video installation experiments, rather poetically, with ideas of interactivity, surveillance and somewhat subversively sharing of data (or privacy). The work operates on two distinct spaces- that of the internet (cyber-space) and the physical (gallery-space). During the period of the art exhibition, the work invites viewers to access via the Ustream app an opportunity to watch or simply gaze at live feeds of the exhibiting space. The app consequently also allows for viewers to provide live feeds of other art spaces they are visiting or even their selfies. Simultaneously this feed is projected in the physical-space of the art gallery, conflating a sense of space with an image of the present space and interspersed with images of another space.

The emerging new order of art is that of interactivity, of “dispersed authorship”, the canon is one of contingency and uncertainty. What is meant by dispersed or distributed authorship? …Thus, at the interface to telematics systems, content is created rather than received. – Randall Packer

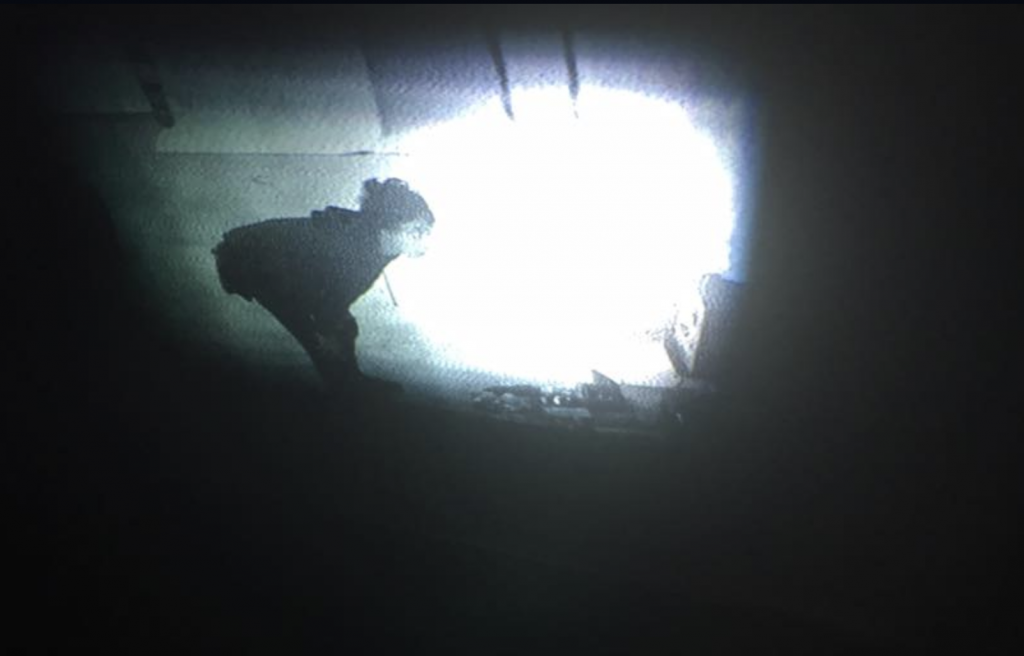

In Lau’s work, a sense of uncertainty and contingency is exacerbated via a viewing of the video images, interspersed with glitch, error and intentionally ‘lo-fi’ in the darkened space. The visitors not only emerge as forming the visuals in the work (visually) but also have the power/propensity to take on part of the “dispersed authorship” generously provided or facilitated by the artist. In Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016) the interface provided by the artist is one of a “poetic embrace of noise and error” as exemplified by the writings and artworks of John Cates. Referencing Cates, we embrace the idea of ‘sharing and tagging one’s activities and whereabouts’ as an interfacing with the work and the gallery space. No doubt, in this techno-social culture, we see an artist like Lau enabling art that is socially performed and poetically embracing ‘random or chance’ performative moments.

Immersion

“The human mind… operates by association,”

Vannevar Bush

At the same time, this work opens up questions and issues related to information sharing and online/internet privacy. As aptly put by Bush, when one sees an interior of a gallery, the immediate reaction would be to relate and associate it with the space they are in. By enabling visitors during and after viewing the exhibit to provide input and co-author the viewing of spaces by others, the immersive space becomes operated by many and not just the author (or artist). With this interactivity, questions of online surveillance and the phenomenon of “checking-in” and “checking-out” of locations using geo-tagging methods are put forth to the visitor and one is left with an artwork that is an open-system in exploring these possibilities and constraints. The immersed visitor can author images while viewing the work in the physical-space or proceed to doing so off-site or at a later time and space, causing an interruption to the installation set-up.

Interruption

Alternating between spaces interrupts one’s viewing of the work and the live-feeds of images and happenings from other art-spaces or for that matter private spaces highlights how we are in a modulated world where our windows are constantly stacked, closed and duplicated.

“It is my belief that computer and media technology will continue to have an increasingly profound effect on everyone on the planet… and if artists don’t jump in and proactively help shape these powerful new tools, it will be left by default to advertisers, the military, organized religion, and sex peddlers.” – Michael Naimark

With Naimark’s quote, we are reminded of the recent development in the invasion of privacy (by major technology corporations) and proliferation of fake news. On many levels, the piece by Lau is an example, albeit a small one of the potential technology (via web-based apps) where a conflation of space can control, manipulate and have a profound impact of peoples experience of art and the world at large. Will we one day ask: The video images lag but is it just interactivity in art?

Video Conference: Exposition 4.0 (2016) Urich Lau. Exhibition: Survey: Space, Sharing, Haunting Curated by Post-Museum The Substation 1 – 30 September 2016