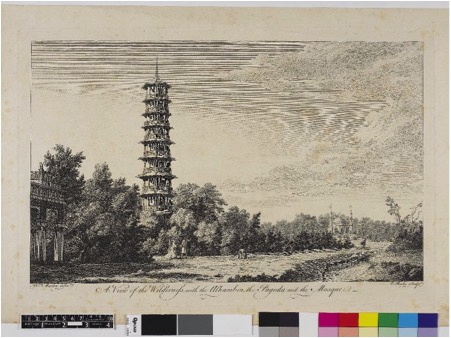

A View of the Wilderness with the Alhambra, the Pagoda and the Mosque, 1763

Sir William Chambers (Scottish, born in Sweden, 1723–1796)

Etching on paper (315 x 473mm)

The National Trust Collection

This etching on paper showcases an artist’s impression of the Kew Gardens’ landscape, with particular interest on three follies within the garden. Namely, the Alhambra, the Great Pagoda and the Mosque. Created in 1763, it is the 43rd plate of Sir William Chambers’ ‘Plans, Elevations, Sections and Perspective Views of the Gardens and Buildings at Kew’, a book published in 1763 upon the completion of the Kew Gardens in 1762. Detailing his architectural work for Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales and mother of George III at Kew Gardens, the book aimed to “promote the fashion for Chinese-style buildings in England’ (Knox, 1994, p. 22), and indeed helped to perpetuate the trend during that period.

Born in 1723, Swedish-born William Chambers was son to a Scottish merchant and at the age of 16, left his education in England to work in the employment of the Swedish East India Company. During his service there, Chambers made two trips to Canton; once in 1743 and another in 1748. Both trips lasted a year. In China, Chambers was fascinated by the culture and documented his experiences fastidiously, making notes and sketches of the strange architecture and scenery. This small act would later be seen as the origin of Chambers’ passion for Chinese architecture and landscaping.

By 1749, Chambers retired from the Swedish East India Company to pursue his interest in architecture. He attended the Ecole de Arts in Paris before enrolling under the tutelage of Charles Louis Clerisseau in Rome to study classical architecture. Upon his return in 1755, he was employed as drawing master to the Prince of Wales, who would later be known as King George III. Work within the royal household proved crucial to Chambers’ architectural career, as it was then the Dowager Princess engaged Chambers to help design the grounds at Kew, as well as beautify it with garden buildings. Chambers used this opportunity to apply his knowledge of Chinese architecture and gardens, and constructed a number of garden buildings for the princess in various fantastic architectural styles, not least of which were 9 classical temples, a mosque, an Alhambra (a type of Moorish palace-fortress) and several Chinese-style follies like the House of Confucius, an aviary and the Great Pagoda. The end result was a feast to the eyes of the Georgian public, and while he was not the first architect to try replicating Chinese architecture, the accuracy of his work on the Pagoda from his experiences in Canton solidified Chambers’ status as the foremost expert in England on Chinese-style architecture.

While some critics nowadays would write off Chambers’ work as tacky or gimmicky, he sparked a fad for buildings and gardens in the Chinese-style, known as chinoiserie. Without Chambers’ experiences in China, subsequent architectural horrors ensued by his imitators’, who based their designs solely on the hearsay of English travelers to Canton or the imagery depicted on the delicate china they brought back. By 1765, the obsession with all things Chinese, or appearing to be, became a lifestyle for the upper classes and reached its peak, with the image of the Cathay (a fantasy world of their imagined China) spawning not just buildings and gardens, but also fashion, decorative arts and tea-drinking. (533 words)

Bibliography

Knox, T. (1994). The great Pagoda at Kew. History Today, 44(7), 22.

The China Pagoda at Kew (1931, Feb 14). South China Morning Post (1903-1941). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1549401535?accountid=12665

The topic your team has chosen is really great. I really enjoyed the layout that was presented in class. I was wondering if you had looked at castle museums in addition to the wax museums? I thought that it might help with your layout. It is really interesting that the lifestyle is being preserved and represented in the layout you have chosen, it actually reminded me of the castle museums (http://www.bradfordmuseums.org/venues/cliffe-castle-museum (for reference)), where they have rooms that are laid out in a way that its occupants would have done it in the past, and in a separate room, they have a glass display case with the objects to focus on the objects, taking them out and looking at them individually. That way you can look at the items as one piece on its own, as well as putting it into perspective into one whole. Hope this helps (:

Thanks for that suggestion, Josephine! It’s a good idea that we may consider but for now, I think that it may not communicate our idea that our objects were used in tandem with one another, in the same sitting even.

Great reference on the castle museums Josephine! Thank you!

There are many ways to display objects, but whatever way each team decides, they need to justify it.

I appreciate the catalog entry Kimberly for many reasons: the first paragraph bring attention to the tree main buildings we need to be focusing on; the second paragraph on the maker; how he became involved in this project; and a nice conclusion. You write well–I hope you have submitted this to turnitin to avoid any unintentional plagiarism.

But, the image and the writing also makes the viewer wonder then about the other two buildings? Did the western consumer separate these various cultures or lump them together? After all, just like those plants, the buildings are sharing the same space…