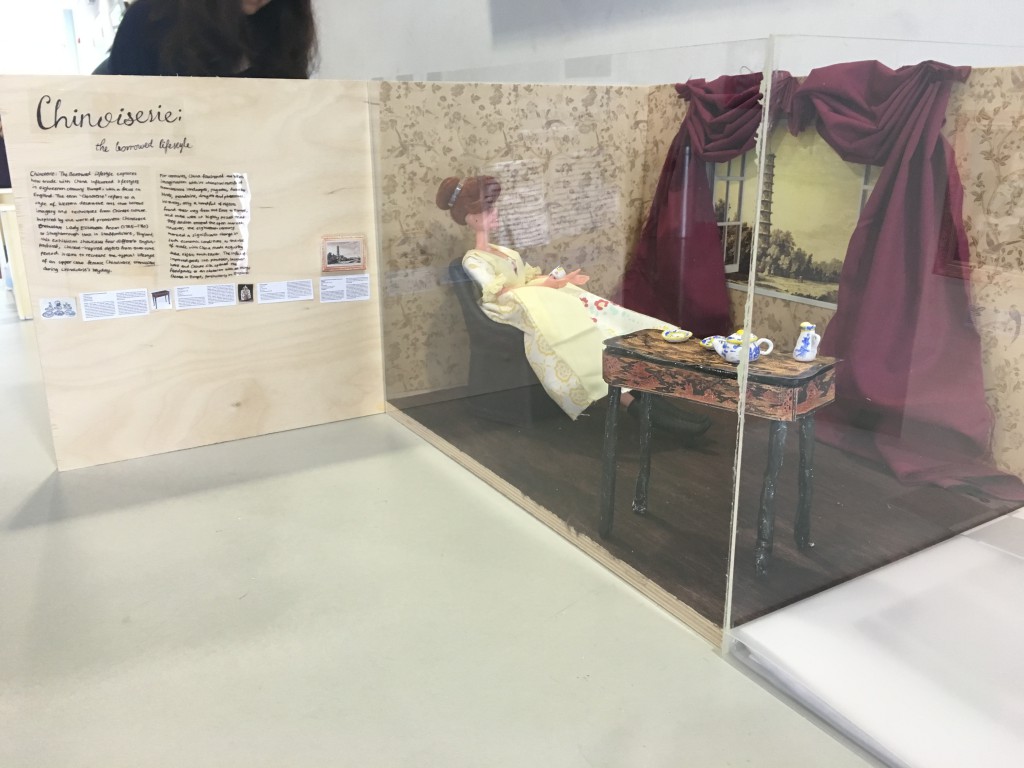

I don’t really have much to say regarding the process of making our exhibition miniature as I left that to the experts, namely Xia Yin, En Ge and Kerr Hui. I just supplied them with the barbie doll and some of the furniture, as well as the digital mock up of my window, before they turned them into the lovely diorama pieces that you see before you.

My job was mainly text-based, meaning that I worked on rewriting our wall text and vetting through everyone’s object labels, catalog entries and the final proposal. I’m not going to lie, it was quite an ordeal handling everyone’s work in this way, especially because the catalog entries would be individually graded, but my group and I believed that it had to be done for consistency’s sake in terms of content and format. I can’t even begin to tell you how excellent it was to get great feedback from Prof Sujatha about our writing, which really justified the splitting of the workload in hindsight.

My job was mainly text-based, meaning that I worked on rewriting our wall text and vetting through everyone’s object labels, catalog entries and the final proposal. I’m not going to lie, it was quite an ordeal handling everyone’s work in this way, especially because the catalog entries would be individually graded, but my group and I believed that it had to be done for consistency’s sake in terms of content and format. I can’t even begin to tell you how excellent it was to get great feedback from Prof Sujatha about our writing, which really justified the splitting of the workload in hindsight.

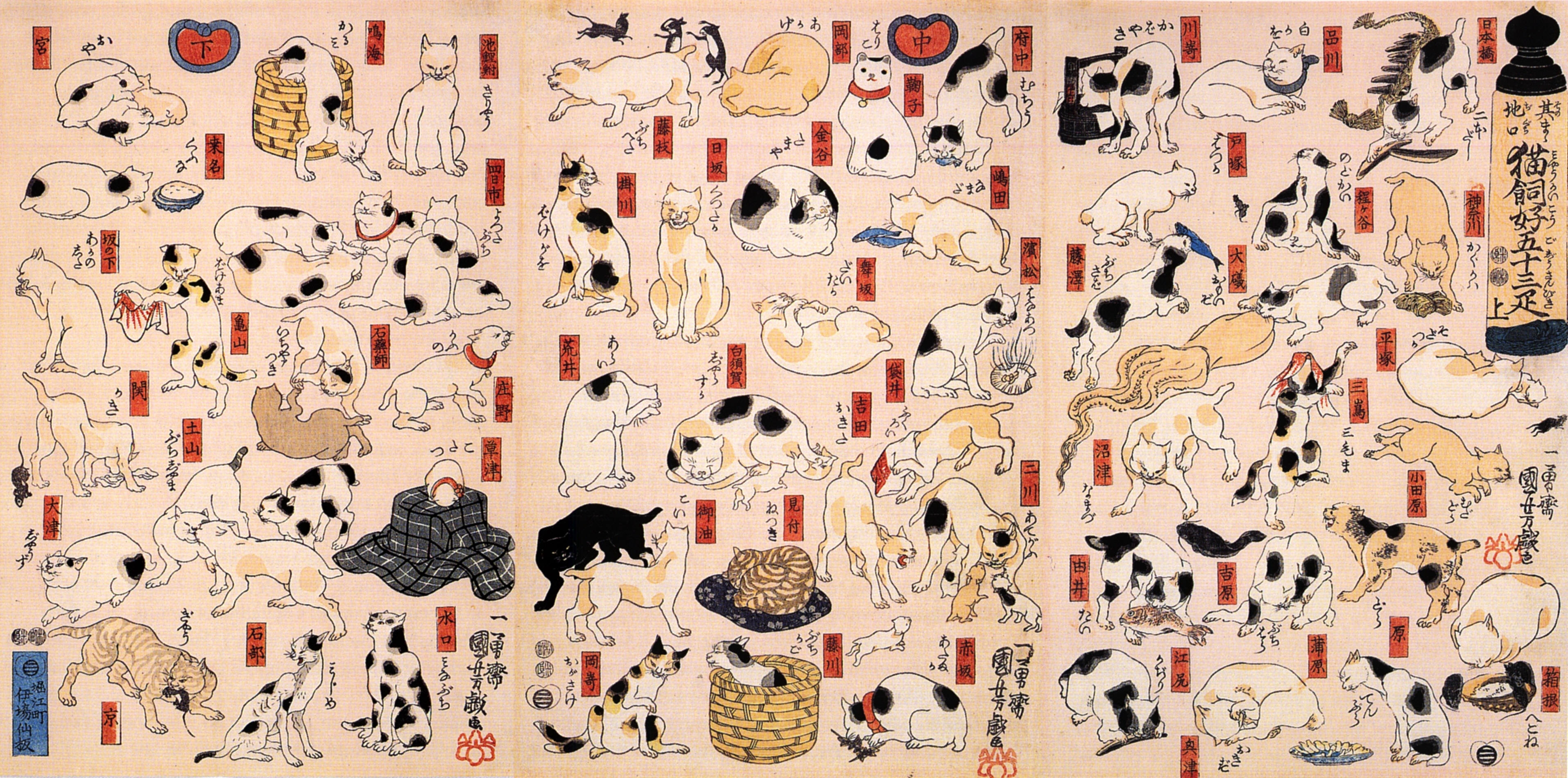

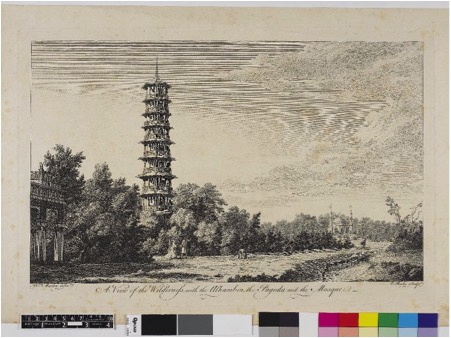

From the project, I learned that it was important to play to everyone’s strengths. I also learned that working on a topic that several other groups were doing as well wasn’t always a bad or unoriginal idea. As seen in the final submission of everyone’s projects, there were very different aspects of Chinoiserie that each group explored and in different ways. This just speaks as to the resonance that this topic had with me and many of my other course mates.

As a whole, this course taught me more than just the art that was produced under colonisation. It gave me an overview of how colonial powers affected the societies that they colonised, for better or for worse. It gave me a concrete idea of the trade that was happening on a global scale, and how it was very similar to trade patterns now despite its slower pace. I learned that foreign trade was a diplomatic art in some cases, and in others, a knife at one’s throat when push came to shove. I gained some idea of organising exhibitions, from conceptualisation to the actual writing of content for it, and overall, had a good time assuming the role of curator.