Spaces: Kolkata, Mumbai and Singapore

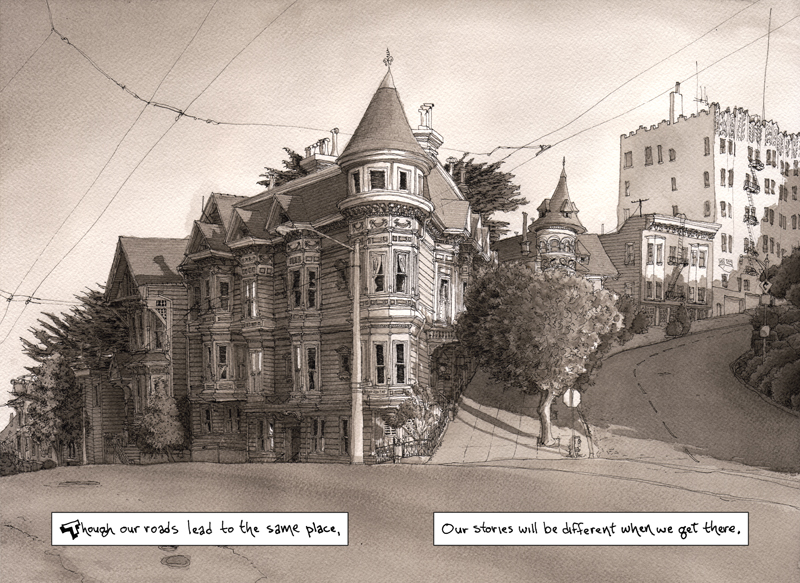

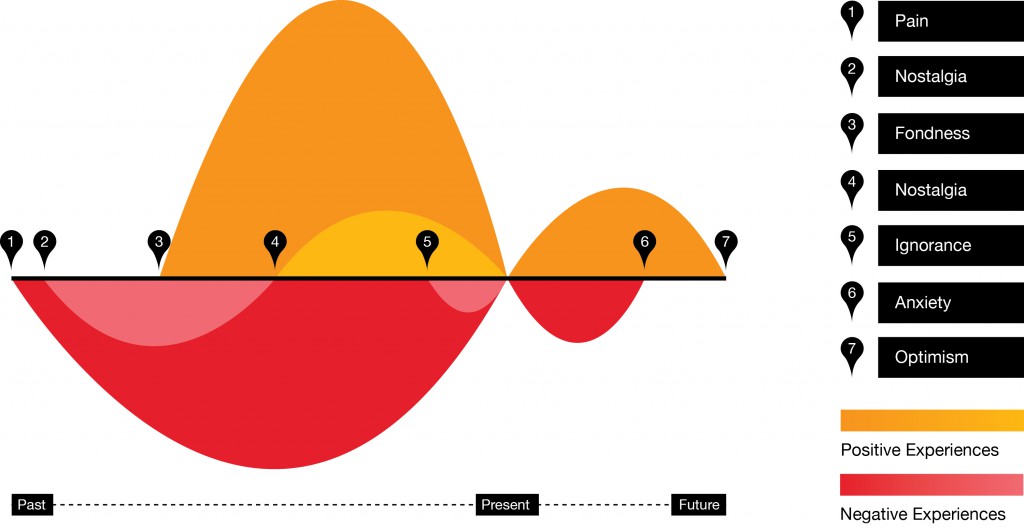

This project uses the idea of walking to express a personal yearning for home. It is the search for a home that is not just a physical space, but also an idea present within objects, people and experiences. Having lived in three cities for most of my life I have always struggled to define what is home for me – and which of the three spaces feel more homely to me. This project took me back to these three spaces. I tried to document these spaces geographically and emotionally – so that I could understand and record the aspects of the space that were significant to my wanderlust. I followed Thoreau’s philosophy and decided to revisit my memories through a walk that lasted seven days.

Kolkata (1992 – 2003)

676 Block O, New Alipore in Kolkata was my home from 1992 – 2003. The project got me to return to this space after more than ten years; upon returning I found that the space was frozen in time and that my memory of it was very accurate.

The timelessness of this space represents the timelessness of the entire city – Kolkata is a city that moves at a slow pace – architecture in this city is also caught in time, things look old and decaying. The most interesting feature of my return was that the house that I grew up in was being demolished that week. The physical disappearance of my home was a source of grief but at the end of my seven-day walk around the space I experienced closure as the documentation of the space brought about a kind of catharsis that helped me rise above my feelings of nostalgia and discomfort.

Mumbai (2003 – Present)

Having moved to Mumbai at the age of 13, at the brink of adolescence, I grew up in this city that never sleeps. Revisiting the space gave me a sense of familiarity that comes through constant engagement with the space. And even though I constantly transit between Singapore and Mumbai, I would say that I still live in Mumbai for my family is there. The human body has to move to accommodate itself in the space and this is something that I realized during my seven-day walk in Mumbai.

Singapore (2010 – Present)

Singapore is a city with an ever-evolving landscape – the permanence of physical spaces is a luxury that people in this country cannot afford to have. In this city, I feel like I am constantly displaced as the space that I live on campus changes every year. The end of each academic year marks my departure from this city, leaving no physical trace behind – almost as if my time here did not exist. The sense of passage of time in Singapore is also very skewed because of the lack of seasons therefore one perceives time to pass based more on personal milestones than environmental change.

Mapping

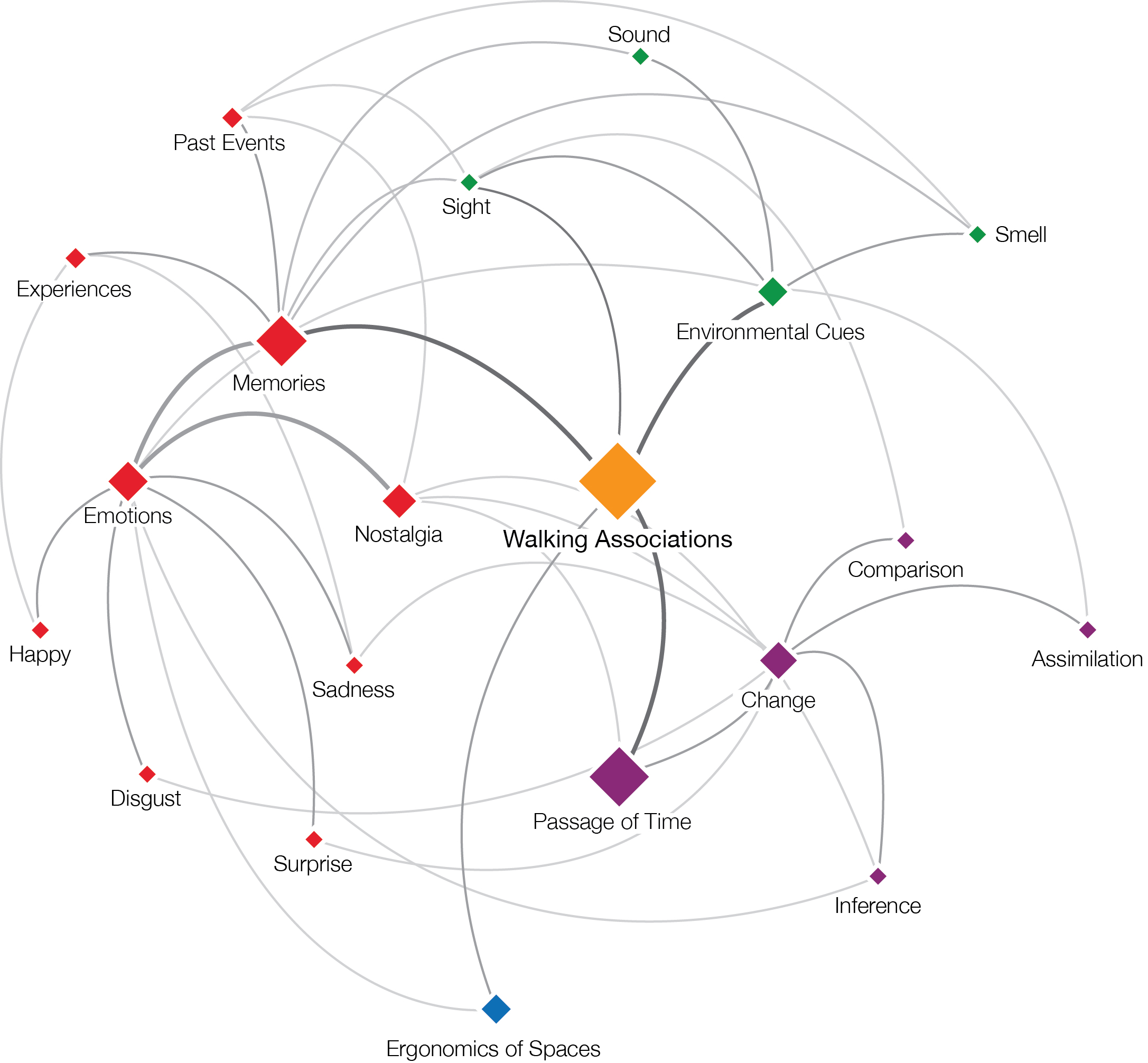

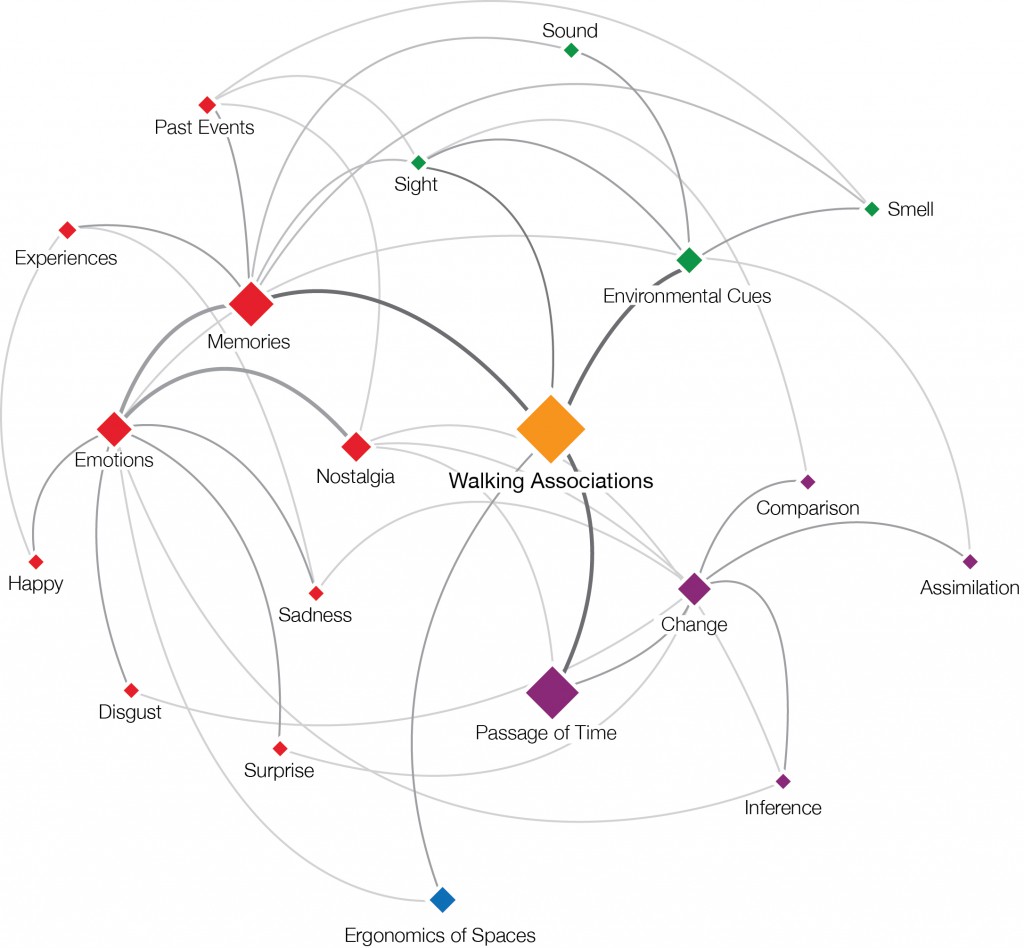

Walking brings the mind and the body together in a manner that can only be described as ephemeral and surreal. The physical mapping of places helps to map the emotional associations with the space. Therefore I walked the areas around my homes in all three cities for a time period of seven days, while documenting the space and my interaction with it.

I recorded the walking data using a GPS device. Each city has its own characteristics and this can be seen in the manner that the human body navigates the city space. The GPS maps showed a lot about the pace of the city and the interaction a pedestrian had with them. The Map of Kolkata looks very organic and leisurely; it consists of slow strolls that don’t give a sense of urgency.

The Map of Mumbai looked chaotic, much like the ambience of the city itself. A pedestrian in Mumbai has to learn to navigate and manoeuvre their bodies in accordance with the space; the moving cars, street vendors and the occasional cattle on the road all affect the way one navigates through this city.

Singapore on the other hand is a much more pedestrian friendly city when compared to Kolkata and Mumbai. Therefore the amount I walked in Singapore in seven days is a lot more than Mumbai and Kolkata combined. There are straight roads and clear pathways, the movement of the body through space is very orderly – frantic yet orderly.

The Making Process

To aptly explain the concept of a personal wanderlust I decided to explore three different avenues. The first is to physically create the GPS maps using screws and thread. Over 1500 screws were used to create the three maps; they were then manually screwed onto a 40 x 60 inch foam boards. The GPS data was projected onto the boards and then the strings were tied so as to make the maps accurate. The process of developing these GPS installations is documented in the images below.

To make the installation more interactive and to give it more meaning, I decided to project the geographical map of the space onto the Kolkata map along with information about the spaces and the emotions they evoked in poems (Appendix A) that I wrote as my response to revisiting the space that once used to be my home.

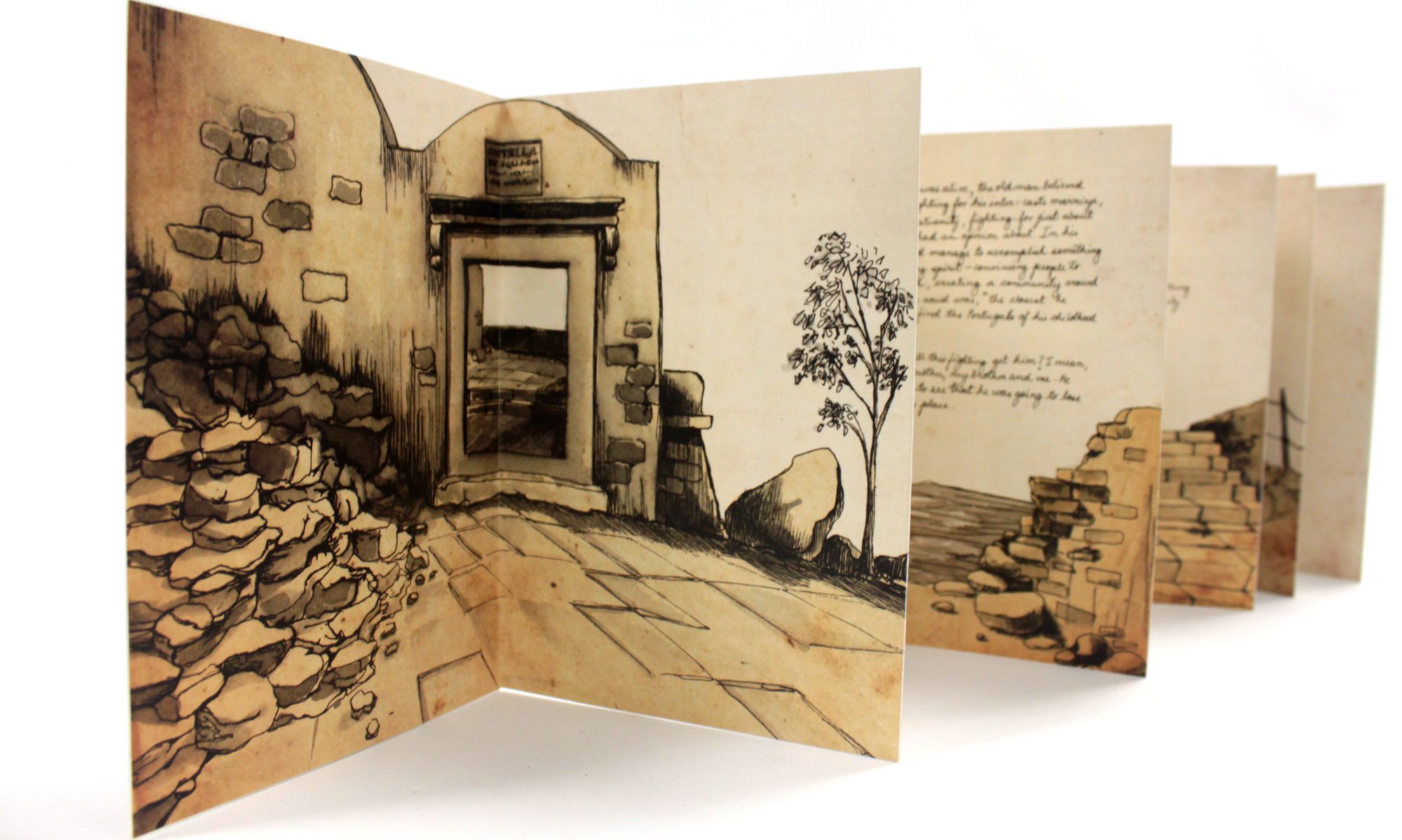

The second deliverable to explore my personal wanderlust is a book. This book features the ten words that are associated with these living spaces and the poems I wrote about these spaces. It is a book of expressive typography – that tries to capture the essence of the space.

The choice of typefaces in the book comes from the most commonly read newspapers of the specific cities. The main newspaper of Kolkata is The Statesman and the dominant typeface in this paper is Baskerville. The most read newspaper in Mumbai is The Times of India, which is printed mostly in Times New Roman. Singapore has the Straits time that uses Miller as its primary typeface. Using these three typefaces I designed a book that expresses the context of the poetry using minimalistic expressive typography.

The visual style of this book is cohesive with the style of the maps i.e. the book is black and white with ample white space. To show the movement of the body through the thoughts on the page, I decided to string the book together with the same string that I used to indicate the walked area on the GPS maps in the installation. This string directs the eye of the reader and also pieces together the narrative.

The third deliverable to really give context to the project is a video documentation of all the spaces around my home from all three cities. The video has an old run down feel to it to signify decay and reminiscence. The voice over in the video is the poetry that I use to describe the spaces – the narrative in the poems is what ties the book, the video and the installations together.

Layout and Planning

In order to successfully show my journey through these three spaces it was decided that the work be shown in an installation space with three walls. Each wall (1.8m wide) would have the map of the GPS walk from the different cities – the central map of my walk in Kolkata would have the interactive projection on top – describing the space and giving it context. To accompany that, I plan to have the video streaming on an iMac to give context to my walk in the other two spaces.

The installation space was carefully planned so as to create a feeling of awe when seen from afar and the proximity of wonder when seen up close. The biggest challenge I faced was to be able to align the projection with the physical map on the wall as the details needed to be precisely matched so that all the points on the installation corresponded to where they were placed geographically on the map that was being projected.