Hypermedia

Description

Week 4: February 6 – 12

The non-sequential linking of information, events, and discrete media. A discussion of the evolution of hypermedia and the non-linear association of information resulting in the collapse of traditional spatial and temporal boundaries. We will begin with Vannevar Bush’s seminal investigation into the concept of the hyperlink through his design of the Memex in 1945, the prototypical multimedia workstation. This will be followed by Ted Nelson’s coining of the term hypertext in the early 1960s, in which non-linear associative thinking was applied to human-computer interaction, concluding with Alan Kay’s creation of the graphical user interface and the first hypermedia system for a personal computer at Xerox PARC in California in the 1970s.

Assignments

Due next week: February 13

Reading

- Ivan Sutherland, “The Ultimate Display,” 1965, Wired Magazine

- Scott Fisher, “Virtual Environments” 1989, Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality

Research Critique

Each student will be assigned a work to research and critique from the following list:

- Morton Heilig, artwork: Sensorama, 1960

- Myron Krueger, Videoplace, 1970

- Char Davies, Osmose, 1995

Write a short 300 word essay summarizing the assigned essays, and apply your understanding of the concept of immersion to the assigned work, and how it expresses ideas found in the readings. Use at least one quote from each reading to support your research and analysis.

The goal of the research critique is to conduct independent research by reviewing the online documentation of the work, visiting the artist’s Website, and googling any other relevant information about the artist and their work. You will give a presentation of your research in class and we will discuss how it relates to the topic of the week: Immersion.

Here are instructions for the research critique:

- Create a new post on your blog incorporating relevant hyperlinks, images, video, etc

- Be sure to reference and quote from the reading to provide context for your critique

- Apply the “Research” category

- Apply appropriate tags

- Add a featured image

- Post a comment on at least one other research post prior to the following class

- Be sure your post is formatted correctly, is readable, and that all media and quotes are DISCUSSED in the essay, not just used as introductory material.

Be prepared to synthesize and present your summary for class discussion next week.

Outline

Artworks for Review

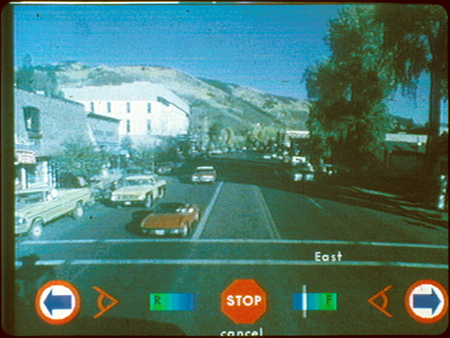

Michael Naimark, artwork: Aspen Movie Map, 1979

“It is my belief that computer and media technology will continue to have an increasingly profound effect on everyone on the planet… and if artists don’t jump in and proactively help shape these powerful new tools, it will be left by default to advertisers, the military, organized religion, and sex peddlers.” – Michael Naimark

Media artist and technologist Michael Naimark has always managed to be well-positioned in seminal developments of interactive multimedia and virtual reality.

During his graduate student years at MIT in the 1970s, Naimark worked on environmental art at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies and on interactive media at the Architecture Machine Group. In 1979, he collaborated on the Aspen Movie Map, the navigable laserdisc tour through Aspen, Colorado dubbed by MIT Media Lab director Nicholas Negroponte as “one of the first examples of interactive multimedia.”

Additional video:

*******

From the Website of Michael Naimark:

The first interactive moviemap was produced at MIT in the late 1970s of Aspen, Colorado. A gyroscopic stabilizer with 16mm stop-frame cameras was mounted on top of a camera car and a fifth wheel with an encoder triggered the cameras every 10 feet. Filming took place daily between 10 AM and 2 PM to minimize lighting discrepancies. The camera car carefully drove down the center of the street for registered match-cuts. In addition to the basic “travel” footage, panoramic camera experiments, thousands of still frames, audio, and data were collected. The playback system required several laserdisc players, a computer, and a touch screen display. Very wide-angle lenses were used for filming, and some attempts at orthoscopic playback were made.

The Aspen Moviemap began as an idea by MIT undergraduate Peter Clay, in collaboration with graduate students Bob Mohl and me. Peter “movemapped” the hallways of MIT in early 1978, as the second videodisc demo made by the Architecture Machine Group.

The Aspen Moviemap was filmed in the fall of 1978, in winter 1979, and briefly again (with an active gyro stabilizer) in the fall of 1979. Many people were involved in the production, most notably: Nicholas Negroponte (Architecture Machine Director, who found support from the Cybernetics Technology Office of DARPA), Andy Lippman (Principal Investigator), Bob Mohl (who wrote his PhD dissertation based on it), Ricky Leacock (MIT Film/Video head), John Borden (Peace River Films), Kristina Hooper (UCSC), and people from the Architecture Machine Group, including Rebecca Allen, Scott Fisher, Walter Bender, Steve Gregory (faculty), and Stan Syzaki. Many more people at ArcMac were involved after production, including Steve Yelick, Paul Heckbert, and Ken Carson. I was at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies and was responsible for cinematography design and production.

*****

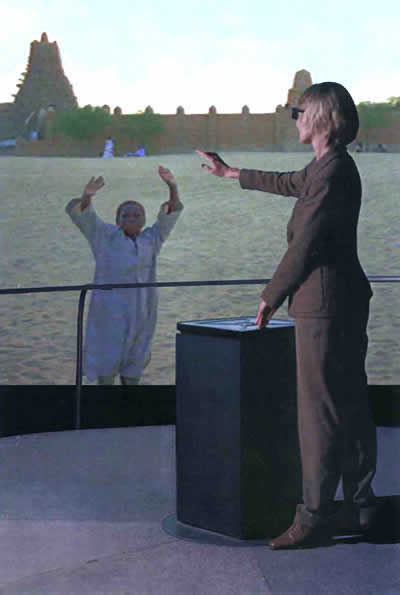

The Aspen Movie Map was Naimark’s first exploration into what he refers to as “surrogate travel,” in which the viewer is transported virtually to another place. The artist has since worked on a series of movie maps of such locations as the wilds of Banff, Canada, the Paris Metro, and the train system in Karlsruhe, Germany. Naimark eventually landed at Interval Research in 1992 – Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen’s Silicon Valley-based think tank – where he created his immersive virtual reality installation Be Now Here.

The work integrates the movement of installation visitors with a slowly rotating floor – spinning in sync with stereoscopic, panoramic film imagery – a surrogate tour of UNESCO World Heritage endangered sites from around the world.

Michael Naimark’s Bio:

Michael Naimark is a producer, inventor, and scholar in the fields of virtual reality and new media art. He is best known for his work in projection mapping, virtual travel, live global video, and cultural preservation, and refers to this body of work as “place representation.” His work has been seen in over 300 art exhibitions, film festivals, and presentations around the world, and he has been awarded 16 patents relating to cameras, display, haptics, and live. Michael has directed projects with support from Apple, Disney, Atari, Panavision, Lucasfilm, Interval, and Google; and from National Geographic, UNESCO, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Exploratorium, the Banff Centre, Ars Electronica, the ZKM, and the Paris Metro. Since 2009, he has served as faculty at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, USC Cinema’s Interactive Media Division, and the MIT Media Lab. In 2015, Naimark was appointed Google’s first-ever “resident artist” in their new VR division, and for Fall 2017, he is Visiting Associate Arts Professor at NYU Shanghai, to teach VR / AR “Fundamentals” and learn about VR / AR in China.

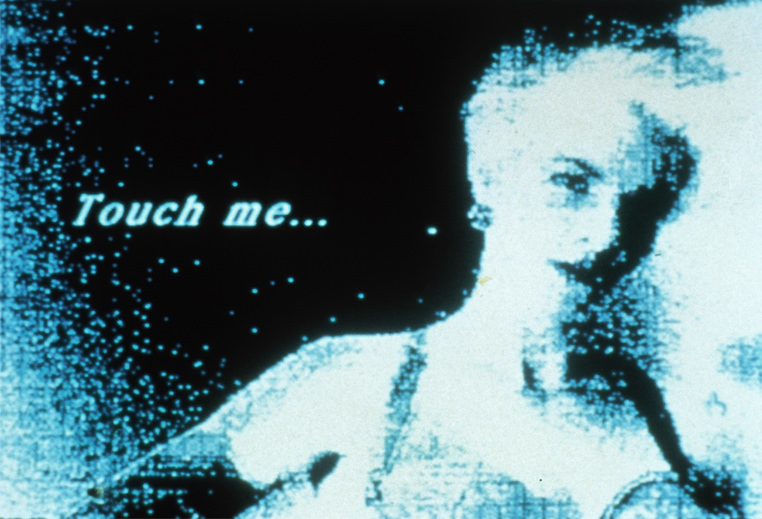

Lynn Hershman, artwork: Deep Contact, 1989

“Traditional narratives are being restructured. As a result, people feel a greater need to personally participate in the discovery of values that affect and order their lives, to dissolve the division that separates them from control, freedom… ” – Lynn Hershman

Media artist Lynn Hershman divides her work into two categories: B.C. (Before Computers) and A.D. (After Digital). The line of demarcation occurred around 1980 as interactive technologies, including personal computers and laserdisc players, became commercially available. In her early performance works and site-specific installations (B.C.), Hershman had begun exploring themes that focused on issues of identity, alienation, and the blurring between reality and fiction.

The first of her interactive works was Lorna (1982), the seminal art videodisc; a labyrinthine journey through the mental landscape of an agoraphobic middle-aged woman. Lorna’s passive relation to media and life is juxtaposed with the viewer’s new found agency to select and reassemble the narrative’s branching themes, stories, interpretations, and conclusions.

In Deep Contact (1984-89), Hershman uses a touchscreen interface to suggest that the viewer can reach through the work’s glass surface, the computer’s “fourth wall.” This type of interactivity constitutes a transgression of the screen, transporting the viewer into virtual reality.

Deep Contact directly involves the body of the viewer/participant who were required to touch the computer screen. Viewers choreograph their own encounters in the vista of voyeurism by actually putting their hand on a touch sensitive screen. This interactive videodisc installation compares intimacy with reproductive technology, and allows viewers to have adventures that change their sex, age and personality.

The leather clad protagonist invites “extensions” into the screen and the screen becomes an extension of the viewer/participant’s hand. Touching the screen encourages the sprouting of phantom limbs that become virtual connections between the viewer and the image. A surveillance camera was programmed to be switched “on” when a cameraman’s shadow is seen. The viewer’s image instantaneously appears on the screen, displacing and replacing the image.

An erotic, interactive touch sensitive videodisk Deep Contact compares intimacy to technology. Viewers can have adventures with the guide and have options of changing sex or personality.

[Deep Contact was created In collaboration with Sara Roberts.]

From Lynn Hershman’s Website:

In this interactive videodisk installation, users are invited to use a Microtouch monitor to directly touch the body parts of a female character named Marion. A surveillance camera registers the visitor’s presence, triggering Marion to entice him or her to begin the action. Depending on what body part is touched, a complex web of episodes unfolds.

Deep Contact, the first interactive touch screen videodisk invites users to touch the guide’s body. Adventures develop depending upon which part of the body is touched, showing 57 segments into the deep parts of the disk.

From MediaArtNet:

Deep Contact: The First Interactive Sexual Fantasy Videodisc

Deep Contact invites participants to actually touch their ‹guide› Marion on any part of her body via a Micro Touch monitor. Adventures develop depending upon which body part is touched.

Marion knocks on the projected video screen asking to be touched. She keeps asking until parts of her body rotate onto the touch sensitive screen and actually are touched. […] In order to truly make the viewer a part of the installation, the Hyper Card was programmed, via a fair light and a small surveillance camera, to be switched ‹on› when the cameraman‘s shadow appears on the screen. Transgressing the screen and being transported into ‹virtual reality› was an important element.

From the Archive of Digital Art:

The next interactive piece, DEEP CONTACT (1989), directly involves the body of the viewer/participant who were required to touch the computerscreen. Viewers choreograph their own encounters in the vista of voyeurism by actually putting their hand on a touch sensative screen. This interactive videodisc installation compares intimacy with reproductive technology, and allows viewers to have adventures that change their sex, age and personality. Participants are invited to follow their instincts as they are instructed to actually touch their guide Marion on any part of her body. Adventures develop depending upon which body part is touched. The leather clad protagonist invites “extensions” into the screen and the screen becomes an extension of the viewer/participant’s hand. Touching the screen encourages the sprouting of phantom limbs that become virtual connections between the viewer and the image.A surveillance camera was programmed to be switched “on” when a cameraman’s shadow is seen. The viewer’s image instantaneously appears on the screen, displacing and replacing the image… An erotic, interactive touch sensitive videodisk DEEP CONTACT compares intimacy to technology. Viewers can have adventures with the guide and have options of changing sex or personality.

From the Thoma Foundation Website:

Since the 1970s, Lynn Hershman Leeson has been a major voice of Cyberfeminism, a field of art that critiques the role of technology in the representation of women’s bodies and identities in our digital era. The first artwork to make use of touchscreens, Deep Contact implicates the viewer as an active participant in manipulating characters within the artwork. Emergent personal technologies such as video dating, video games and the desktop computer in the mid-1980s prompted the artist to respond with Deep Contact, which makes a statement about the ways electronic telecommunications alter the structure, speed and objectives of human desire.

The video narrative begins with a seduction: “Try to reach through the screen and touch me. Touch me! Try to press your way through the screen,” says Marion, knocking on the screen. The hostess Marion guides viewers through a navigable, choose-your-own-adventure-style journey through different scenes and characters such as a garden, a tavern and virtual TV stations. There is no clear end to the narrative. One meets a Zen master and a demon as representations of good and evil, as well as the artist playing herself. Touching different parts of Marion’s digital body leads you to different video chapters. There are seventy-one segments to choose, with a map on the nearby wall to help guide you.

Mark Amerika, artwork: Grammatron, 1997

From the project Website:

The GRAMMATRON project is a “public domain narrative environment” developed by virtual artist Mark Amerika in conjunction with the Brown University Graduate Creative Writing Program and the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Graphics and Visualization Center as well as with the support of many individuals without whom none of this would be possible.

The project consists of over over 1100 text spaces, 2000 links, 40+ minutes of original soundtrack delivered via Real Audio 3.0, unique hyperlink structures by way of specially-coded Javascripts, a virtual gallery featuring scores of animated and still life images, and more storyworld development than any other narrative created exclusively for the Web. A story about cyberspace, Cabala mysticism, digicash paracurrencies and the evolution of virtual sex in a society afraid to go outside and get in touch with its own nature, GRAMMATRON depicts a near-future world where stories are no longer conceived for book production but are instead created for a more immersive networked-narrative environment that, taking place on the Net, calls into question how a narrative is composed, published and distributed in the age of digital dissemination.

The essential parts of Grammatron:

Grammatron “high bandwidth” version, consisting of an automated slide show of text and image.

Grammatron “low bandwidth” version, consisting of a hypermedia, non-linear story environment.

Hypertextual Consciousness, a theoretical artistic statement on the concept of Grammatron

Reconfiguring the Author, a theoretical artistic statement on the author of Grammatron, Mark Amerika

Reconfiguring the Author: The Virtual Artist In Cyberspace is many things at once including a research paper, a pseudo-autobiographical narrative, a technical “white paper”, a textual documentary, a survey of the state-of-the-art of contemporary writing, a self-reflexive metafiction on the “public domain narrative environment” called GRAMMATRON and, last but not least, an exploration into the science of writing as it gets teleported into the electrosphere. It is an elaborate extratext that attempts to challenge the critical strategies employed by most academic theorists confined to the print-publishing model and, as such, is intimately connected to the network-distributed milieu the GRAMMATRON project circulates in.

Readings

Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think” 1945, Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality

This has not been a scientist’s war; it has been a war in which all have had a part… What are the scientists to do next? … Now, as peace approaches, one asks where they will find objectives worthy of their best.

Vannevar Bush, the great original thinker of information technology and chief scientist to President Roosevelt during World War II, makes reference to the military-industrial complex which he helped put together under President Roosevelt during World War II. He now issues a call-to-action to use the technology for the betterment of mankind.

There is a growing mountain of research. But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends.

Bush acknowledges the need to cope with increasingly complexity and abundance of information: foreshadowing the emergence of information technology and computers.

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record.

He suggests here there is a need to aggregate, consolidate, provide access and ultimately to interconnect this increasing information in the form of papers, journals, books, etc.

He walks us through a history of computing, which in 1945, had still not produced what was necessary:

Two centuries ago Leibnitz invented a calculating machine which embodied most of the essential features of recent keyboard devices, but it could not then come into use.

Babbage, even with remarkably generous support for his time, could not produce his great arithmetical machine.

He doesn’t mention the ENIAC here, but this would have been the latest computing machine, created in the same year 1945, that pointed to the future of information technology.

The camera hound of the future wears on his forehead a lump a little larger than a walnut. It takes pictures 3 millimeters square, later to be projected or enlarged…

This reminds us in many ways of the built in Webcam on our computers and mobile devices, which we now use to capture documents, ourselves, and the world around us as many times as we like.

It may well be stereoscopic, and record with two spaced glass eyes, for striking improvements in stereoscopic technique are just around the corner.

Not did he look ahead at the miniaturized camera, but also stereoscopic images, the basis of virtual reality. Now we can imagine Google Glass, etc., for capturing and seeing the world in 3D.

Often it would be advantageous to be able to snap the camera and to look at the picture immediately.

He saw the shift from film photography created with wet solutions, to dry photography, which would ultimately be digital: instant imaging as he predicted.

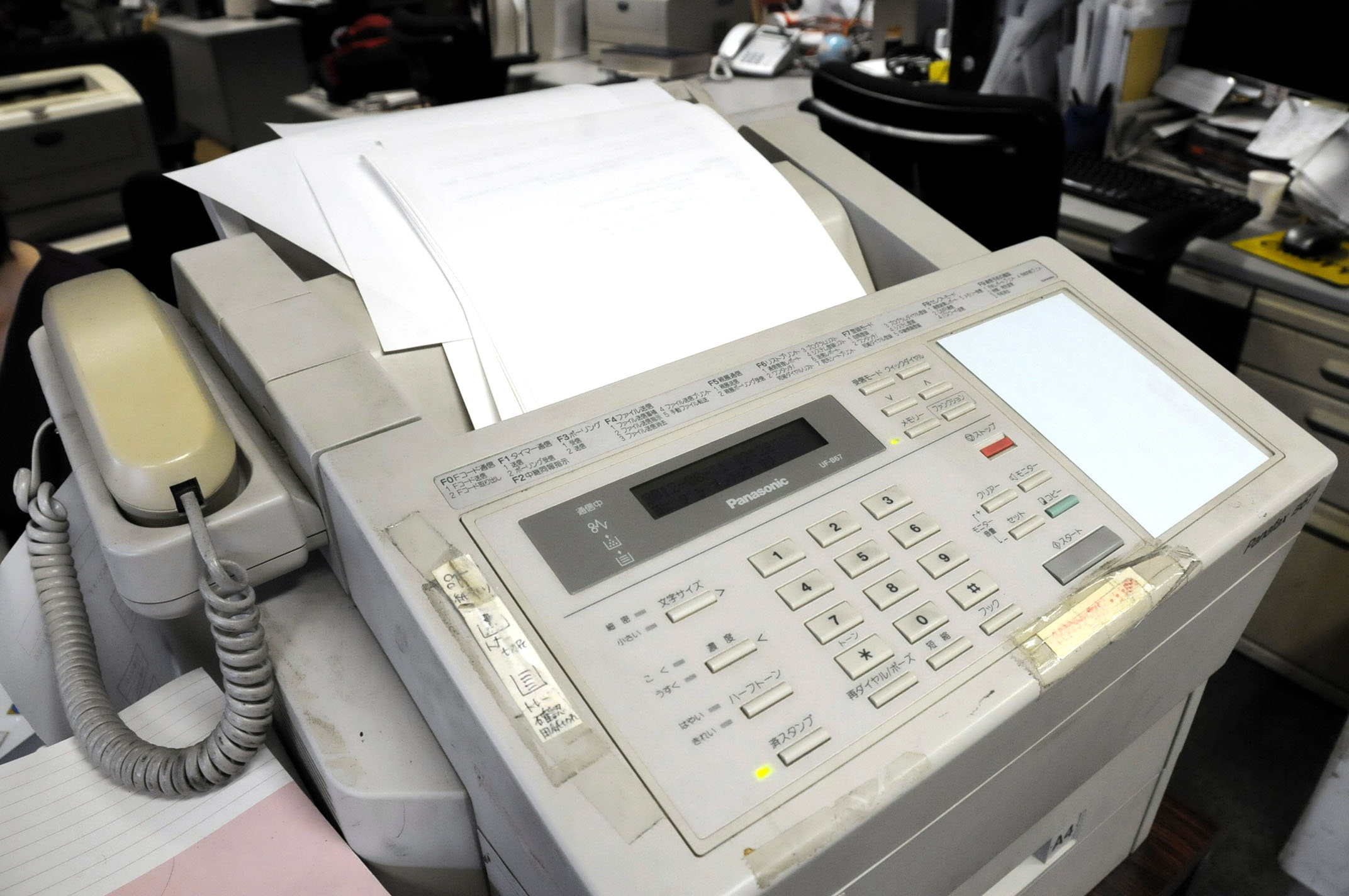

This scheme is now used in facsimile transmission. The pointer draws a set of closely spaced lines across the paper one after another.Thus, when the whole picture has been covered, a replica appears at the receiving end.. of making its picture at a distance.

He he foresaw the fax, phone line transmissions, and ultimately networked forms of tele-communication as an extension of the image and document making process.

Like dry photography, microphotography still has a long way to go. The basic scheme of reducing the size of the record, and examining it by projection rather than directly, has possibilities too great to be ignored…The Encyclopoedia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox..

Here we see the miniaturization of information, data, so that it can be stored in large quantities and retrieved quickly: the essence essentially of the database and its records, which can be enlarged for purposes of viewing on the screen.

Even the modern great library is not generally consulted; it is nibbled at by a few.

This means with the abundance of information we have at our disposal, we need new systems for their documentation, access, viewing, sharing, and distribution.

In the Bell Laboratories there is the converse of this machine, called a Vocoder. The loudspeaker is replaced by a microphone, which picks up sound. Speak to it, and the corresponding keys move. This may be one element of the postulated system.

He foresaw voice recognition as an essential part of the information storage and retrieval system, today we have Siri and forms of artificial intelligence that enable recording and access.

If we recorded them positionally, simply by the configuration of a set of dots on a card, the automatic reading mechanism would become comparatively simple. In fact if the dots are holes, we have the punched-card machine long ago produced by Hollerith for the purposes of the census, and now used throughout business.

He saw the need for memory and storage media, long before floppy discs, CD’s, DVD’s and hard drives. He was aware of the Hollerith punch card at the time, an early form of programming and memory storage.

It is a far cry from the abacus to the modern keyboard accounting machine. It will be an equal step to the arithmetical machine of the future.

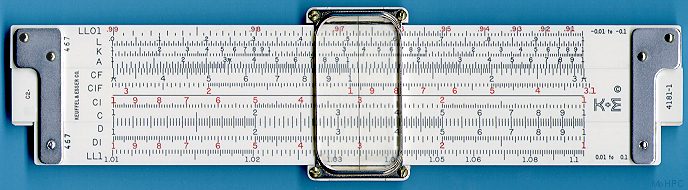

In his time, there was no market for computing machines, because they didn’t yet exist, even electronic calculators, at the time, the slide rule was the primary means of mathematical calculation.

We may some day click off arguments on a machine with the same assurance that we now enter sales on a cash register. But the machine of logic will not look like a cash register, even of the streamlined model…for we can enormously extend the record; yet even in its present bulk we can hardly consult it..

He realized that the machine of the future must be capable of advanced forms of logic, not just speed, with algorithmic solutions for computation and problem solving. It’s not enough to just store information, it needs to be properly aggregated, filtered, searched, selected, and interpreted, such as we do in OSS with taxonomies.

Section 6

Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing.

The idea of indexing, the organization of data, the systems of linking data is at the heart of Bush’s invention of hypermedia.

The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain… Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

Here he makes the connection between indexing and the associative ways in which the mind works. This is absolutely fundamental to our understanding of hypermedia, and the way in which we link and association information for purposes of retrieval.

Selection by association, rather than indexing, may yet be mechanized.

So here he pulls together the hypermediated concept of association with its mechanization, as he has built up to at this point.

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.. Most of the memex contents are purchased on microfilm ready for insertion. Books of all sorts, pictures, current periodicals, newspapers, are thus obtained and dropped into place.

At this point he conceives of the memex, the extension of memory as a system for storing all of our historical and cultural information.

Section 7

This is the essential feature of the memex. The process of tying two items together is the important thing.

This is the idea of the hyperlink, in a nutshell.

Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item… Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.

This idea of building a trail of associations is directly related to the browser history of links. Perhaps even today, we fall short of the ability to adequately create and publish these booklink histories?

He has built a civilization so complex that he needs to mechanize his records more fully if he is to push his experiment to its logical conclusion and not merely become bogged down part way there by overtaxing his limited memory.

A call-to-action, which is the precise result of this essay, having inspired generations of scientists leading up to the invention of the personal computer to the mobile devices of today.

They have enabled him to throw masses of people against one another with cruel weapons. They may yet allow him truly to encompass the great record and to grow in the wisdom of race experience.

To turn military technology into information technology that benefits mankind.

***********

Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg, “Personal Dynamic Media,” 1977, The New Media Reader

Several years ago, we crystallized our dreams into a design idea for a personal dynamic medium the size of a notebook (the Dynabook) which could be owned by ever one and could have the power to handle virtually all of its owner’s information-related needs.

Like the Memex, the Dynabook was a later prototype that became what is now the standard for the laptop computer and tablets. A “dynamic book” that would contain all of our information and creative work.

“Devices” which variously store, retrieve, or manipulate information in the form of messages embedded in a medium have been in existence for thousands of years.

We can think of the Abacus as one of the earliest calculators, or the stone tablets, the illuminated manuscripts, etc., which preserved and rendered information before the digital age.

For most of recorded history, the interactions of humans with their media have been primarily nonconversational and passive in the sense that marks on paper, paint on walls, even “motion” pictures and television, do not change in response to the viewer’s wishes. A mathematical formulation—which may symbolize the essence of an entire universe—once put down on paper, remains static and requires the reader to expand its possibilities.

Thus, these previous media were not interactive, they were not electronically or digitally linked, and thus the information was not easily accessible or retrievable, but it was well preserved!

The ability to simulate the details of any descriptive model means that the computer, viewed as a medium itself, can be all other media if the embedding and viewing methods are sufficiently well provided. Moreover, this new “metamedium” is active—it can respond to queries and experiments—so that the messages may involve the learner in a two-way conversation.

With the Dynabook and the work of Alan Kay, they conceived the idea of the “metamedium” as a device that could do all things, many mediums integrated together, which we can associate with Wagner’s concept of the gesamtkünstwerk.

Imagine having your own self-contained knowledge manipulator in a portable package the size and shape of an ordinary notebook… we should investigate the possibility of giving each person his own powerful machine.

This is essentially the description of the laptop computer, which did not come into vogue until the 1990s. This device was based on the concept of the Dynabook.

… we became interested in focusing on children as our

“user community.”

The research at Xerox PARC was focused on children, how they learn, their intuitive abilities, and how to design computers that were simple enough to be used by children.

children really can write programs that do serious things… Second, the kids love it! The interactive nature of the dialogue, the fact that they are in control, the feeling that they are doing real things rather than playing with toys or working out “assigned” problems, the pictorial and auditory nature of their results, all contribute to a tremendous sense of accomplishment to their experience.

The idea of the interactive experience was much more in tune with the child’s sensibility of play in the act of learning through doing, what Kay considered kinetic learning using graphical symbols or icons.

The Dynabook can be used as an interactive memory or file cabinet. The owner’s context can be entered through a

keyboard and active editor, retained and modified

indefinitely, and displayed on demand in a font of

publishing quality.

We can see how much the description of the Dynabook emulates the Memex, as a “file cabinet” and storage device with keyboard and editor for storing and retrieving information.

The non-sequential nature of the file medium and the use of dynamic manipulation allows a story to have many accessible points of view.

Here we see the associative thinking as also expressed in the Memex.

Multiple windows, as shown above allow a document (composed of text, pictures, musical notation) to be created and viewed simultaneously at several levels of refinement.

With the Smalltalk operating system, it became possible to view multiple windows and documents on a single screen, bringing with it the possibility of multi-tasking and displaying multiple views simultaneously.

The many small dots required to display high-quality

characters (about 500,000 for an 8-1/2″ × 11″ sized display) also allow sketching-quality drawing, “halftone painting,” and animation.

The Dynabook can act as a “super synthesizer” getting direction either from a keyboard or from a “score.” The keystrokes can be captured, edited, and played back.

The early computing at PARC transformed the device into a synthesizer for the programming and creation of real-time music.

In a very real sense, simulation is the central notion of the Dynabook. Each of the previous examples has shown a simulation of visual or auditory media.

The Smalltalk system was designed to simulate sound, motion, cel animation, imaging, fonts, graphics, etc., as a multimedia device capable of all forms of media manipulation.

Animation can be considered to be the coordinated parallel control through time of images conceived by an animator. Likewise, a system for representing and controlling musical images can be imagined which has very strong analogies to the visual world. Music is the design and control of images (pitch and duration changes) which can be painted different colors (timbre choices); it has synchronization and coordination, and a very close relationship between audio and spatial visualization.

Like Wagner’s gesamtkünstwerk, we can see how the Smalltalk system was intended to synthesize visuals and music into a single integrated form in the digital realm.

What would happen in a world in which everyone had a Dynabook? If such a machine were designed in a way that any owner could mold and channel its power to his own needs, then a new kind of medium would have been created: a metamedium, whose content would be a wide range of already-existing and not-yet-invented media.

We now live in a world where everyone has a Dynabook (or at least many people), so what has the world become in the context of a hypermediated global constellation of multimedia computers?