Category: Narratives for Interaction

Your room: all questions done

A simple room. Images appear on the walls.

Does Minecraft have a narrative?

(Just a long ramble that came to me in the middle of class because I loved where the discussion was going.) As we discussed interactive narratives today, it began to seem to me that Minecraft was the one game I knew that bore all the features we seemed to so deeply crave–except for one problem: Minecraft doesn’t seem to have any narrative to speak of.

I am of the belief that as a game approaches maximum interactivity–that is, as the player’s will increasingly becomes the sole factor shaping the narrative experience–its structure must grow increasingly “porous”. There is no room for high contextualisation, because just as it is much easier to damage a smartphone such that it loses functionality than it is a chalkboard, narratives with high contextuality are extremely difficult to mold and adapt because any change threatens to damage whatever makes them tick.

The ultimate interactive experience is, of course, life itself, and to create a game so responsive without the developers having to account for every single choices in analogue (identifying discrete option paths and scripting out the individual outcomes), it needs to mirror real life in several ways. This implies that as a game becomes more interactive, it also necessarily loses elements that would qualify it to be a narrative, simply because that is the nature of interaction. That is why I’d propose that Minecraft is the closest thing to a model of a true interactive narrative that exists at present, being an excellent balance between both.

Is it a narrative? This is a game that, to me, straddles the boundary between narrative and pure organic experience. Being an open sandbox game where one can do practically anything one chooses with the materials made available, one might initially be tempted to believe that it is entirely absent of a narrative, but I would dispute that.

For simplicity’s sake let’s say that a narrative is an emotional thread realised through events involving characters, organised in the ternary structure of introduction, body, and conclusion, in which the conclusion offers a satisfying resolution to that which is troubled in the prior segments. This emotional core is what makes the story worth traversing, the resolution being the reward of the turmoil–and learning–that one endured throughout.

To me, Minecraft has a narrative, and that narrative is self-generating; it emerges as the player plays, within the framework supplied by the game. It has an emotional thread, and that thread is survival and discovery. The feeling of a story arc lies, I think, in the process of realisation one undergoes, as one comes to understand that the world is vast and that one is tiny, and that one’s thirst for exploration is endless as the world within which one resides

It is a very particular kind of “empty world experience” as described in class. The world bears evidence of a past and of outside influences–other consciousnesses shaping the landscape, building monuments outside of one’s notice–and within that framing, AI monsters and creatures are imbued with intelligence. Within the framing, the randomness becomes indicative of organic life appearing and morphing outside one’s control. The ever-present threat of death and the pressing need to survive, to move, maps a trajectory or various trajectories along which one’s self-generating narrative proceeds. One moves forward because 1) there are things one must discover, and 2) one is afraid to die.

And it would be wrong to say that there is no ultimate goal in even a concrete sense. There is a distant goal, an ultimate quest (the same way religion or existentialism supplies our lives with an ultimate quest, perhaps?), in the End, a realm that embodies the very concept of ending, a realm with as much psychological and philosophical dimensionality as it is has physical aspects, an abyss into which the very universe, and the reason for its existence, threatens to be swallowed.

But this ending is so impossibly difficult (probably requiring hundreds of hours of playtime on average), and it can be arrived at in so many different ways, that it never feels omnipresent in a way end goals tend to be in other games. Minecraft questions whether a game’s raison d’etre necessarily has to be the ending, the boss fight, by presenting us with an ultimate objective which one is free to ignore if one does not think it will improve the gaming experience (I mean, if you think about it, you could choose to ignore the plot or the ending in any game, in favour of indefinite exploration)–something that one will arrive at “someday”, a goal that oscillates between concrete and immaterial–a feeling of one, rather.

There is a reward to “completing” the game, however, and that reward is an explanation. As the credits roll, one is presented a short story that offers a troubling yet immensely moving ontological reflection on the meaning of one’s existence within the world of the game, and why one plays at all.

I think Minecraft has a narrative–perhaps in the loosest sense–but it has a narrative, because I decided to play it and inhabit its world as if it does, and yes, not everyone will. To me, it represents the closest thing to a truly interactive narrative.

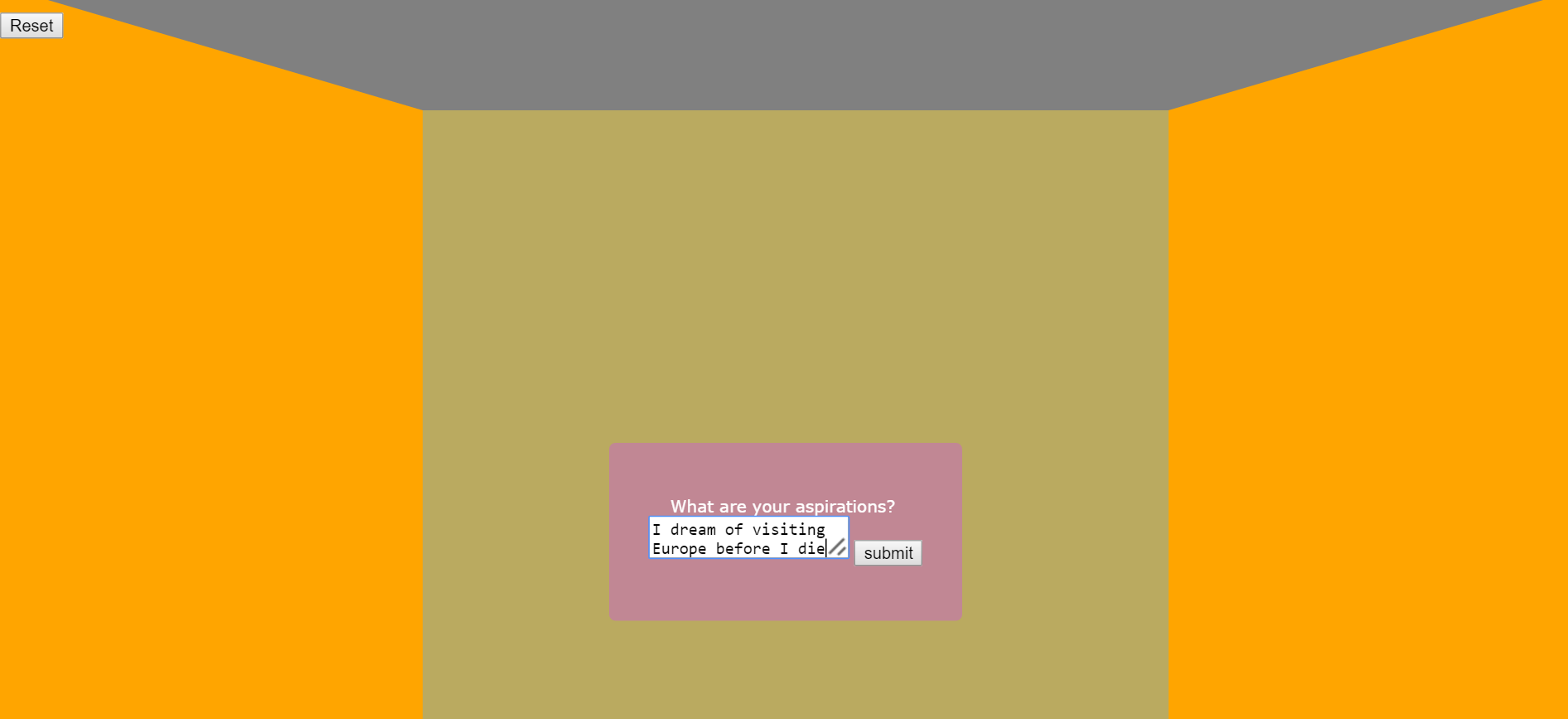

I’ve been working on something on and off over the weekend. This is as far as I’ve gotten (a “room” with poor perspective and three windows). Right now, only three room sizes and two window configurations exist.

your room

Idea 1: Personalised room

Personality quiz that populates “your room” as you answer questions.

Wide room, scrollable. A visual representation of one’s subconscious personality. Implying environment and world.

Save and share your room with a name and a password.

- Four paintings, variable sizes and positions.

- Windows, variable sizes and positions.

- Wall panelling material.

- Three overlayed sounds: ambient, possibly “diegetic” music.

Idea 2: Collaborative room

Everyone contributes to a single room, words that are frequently used in the room become features of the room. There is a live chat from which words are pulled.

A modified “chatbot” idea

In light of my musings while reading The Garden of Forking Paths, I have decided to modify my chatbot idea and possibly incorporate elements of my other two ideas into it.

Randomness, I believe is key to creating an interactive experience that is rich and possible to execute in a short time frame. It is humanly impossible for one to account for all the possible decisions made by the player and offering only discrete options that lead to discretely branching outcomes will inevitably cause the player to be aware of the fact that their decisions are leading them down definite paths, ruining the illusion of choice.

However, I must also think about managing all the information players add to the database and how the player experiences the game. Instead of having the player type sentences into a text input field (which can be mechanical and dull), I have been contemplating other easy ways by which they may convey something personal but not private: a link to an image they like, a word they like, answers to a personality quiz, “select which one(s) you like most”?

I just started learning AJAX today and if I am able to finish learning it in time, I could create a real-time feed of these submissions, and this could be extremely exciting.

Reflections on The Garden of Forking Paths

I’ve always held a fascination towards branching narratives. Oddly enough, however, I rarely derived much enjoyment from experiencing Choose Your Own Adventure stories (I own one such book and I found it frustrating more than anything) and Twine stories, much less creating them.

As I was reading The Garden of Forking Paths, and particularly towards the climax, the story exploded at once into a thousand; I felt like I was experiencing so many concurrent timelines, because the story demanded that I imagine them–not only in Doctor Albert’s creation, and not only within the life of the fictitious Doctor Yu Tsun, who perhaps knew that his story could have gone a billion other ways, but also within my own: how, at every second, a thousand options lie open to me, to advance any one of countless stories that I could potentially live.

And then it hit me that the reason linear narratives are so exciting is suspension of disbelief. The reader places oneself within the shoes of the main character, causing them to forget that the events of the story are predetermined. As in real life, the story suddenly becomes a garden of possibility, every single branch as possible as every other, and moving forward in the narrative merely feels as natural as living one’s life.

The reason actual branching narratives are rarely satisfying is that the act of traversing the branching paths calls attention to the act of reading or experiencing the story. One becomes aware of the artificial attempt to recreate the sense of possibility, when the effect is the reverse: the reader realises that the possibilities are finite because suspension of disbelief is broken and the reader realises that all the possibilities exist in physical form somewhere, and that that indeed means that they are finite. I have never seen any branching narrative succeed properly in its execution. There are often too few branches–and I, as the player, can easily access all of them in a single sitting, causing the story to feel nearly as finite as a linear one would be.

Doctor Albert’s story within the story is an attempt to crystallise that experience, but I do not find the concept of the story in itself very appealing. What I do find appealing is how the concept of the branching path manifested in Yu Tsun’s narration, as he killed Albert, how he suddenly saw all the possible outcomes of his act fanning out before him.

I believe the only true way to capture the idea of branching possibilities in a narrative form that can be experienced is to introduce randomness into the setup, such that there truly were an infinity of different stories one could experience. This is why games succeed in a way hypertext stories do not where branching narratives are concerned.

Puzzle ideas

- All puzzles are linked to one of four topics, equivalent to a branching narrative: the player gets to decide which thread to pursue first (a “thread” being a series of puzzles that must be solved in sequence as each either unlocks or is key to solving a subsequent one), even though all four “routes” are available for solving all the time.

-

- Four seasons?

- Signs of the zodiac?

- Four elements?

- Clues in plain sight: A list of news article titles that are actually mini-riddles; they will share a common theme so that the player can figure everything out by finding the relationship between them. For example, each riddle might refer to a cardinal direction–north, south, east, west. One might use the sequence to solve a different puzzle, like moving across a grid.

- Hidden clues: the player must do creative things to discover them, like run some JS code in the console. Risky, because this might tempt them to read the source code.

- Could use simple code to replace clues.

- Encoded clues: messages or directions converted to less direct forms, like converted to binary and then encoded in black and white squares, like a punch card.

- The marquee at the top of the page serves as a consistent source of notifications and updates on puzzle progress. It informs the player that they’ve completed particular milestones.

Today’s presentation

The Hero’s Journey in Undertale (True Pacifist)

The Call to Adventure

The hero begins in a situation of normality from which some information is received that acts as a call to head off into the unknown.

Frisk falls and lands in the Ruins inside Mount Ebott.

Refusal of the Call

Often when the call is given, the future hero first refuses to heed it. This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the person in his or her current circumstances.

Frisk meets Flowey, who pretends to be kind initially, but then attempts to kill Frisk, gloating about the fact that it’s “kill or be killed” in this world. They are incapable of defending themself. A moment of despair ensues as death approaches.

Supernatural Aid

Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously, his guide and magical helper appears or becomes known. More often than not, this supernatural mentor will present the hero with one or more talismans or artifacts that will aid him later in his quest.

Toriel kills Flowey at the last moment, and offers to guide Frisk. She takes them in as a foster mother, and teaches them how to deal with monster encounters—by befriending them—and shows them how to solve puzzles. She also give them the mobile phone, an important item in their quest.

Crossing the Threshold

This is the point where the person actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of his or her world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are not known.

After entering Toriel’s home, Frisk attempts to leave the Ruins via an underground passageway, but Toriel insists on keeping them inside the ruins, where it is safe.

Belly of the Whale

The belly of the whale represents the final separation from the hero’s known world and self. By entering this stage, the person shows willingness to undergo a metamorphosis.

Frisk faces Toriel, wherein they are challenged to take on the person who taught them how to navigate this world. They convince her to let them leave the Ruins. She is moved by their determination and lets them go. The belly of the whale manifests as a long underground passageway, at the end of which lies the decisive fight. Frisk passes through a gate into the outside world.

Initiation

The Road of Trials

The road of trials is a series of tests that the person must undergo to begin the transformation. Often the person fails one or more of these tests, which often occur in threes.

Frisk is stalked by various servants of the king, all tasked to capture them. They encounter various puzzles and must solve them to proceed. They also encounter increasingly powerful (and bizarre) monsters, whom they handle in the same way–by befriending them–and in so doing learns that every single monster has the capacity for kindness.

The Meeting with the Goddess

This is the point when the person experiences a love that has the power and significance of the all-powerful, all encompassing, unconditional love that a fortunate infant may experience with his or her mother. This is a very important step in the process and is often represented by the person finding the other person that he or she loves most completely.

Frisk meets various characters—some of them former enemies—with whom they establish friendships. This game doesn’t concern itself overly with romance; it is friendship that is the world-saving force in this story.

Woman as Temptress

In this step, the hero faces those temptations, often of a physical or pleasurable nature, that may lead him or her to abandon or stray from his or her quest, which does not necessarily have to be represented by a woman. Woman is a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life, since the hero-knight was often tempted by lust from his spiritual journey.

Frisk enters the True Laboratory, where they learn the story of King Asgore and his son Asriel, and the horrifying things that were done in the name of breaking the barrier between the Underground and the human world. They may begin to doubt the rightness of their quest.

Atonement with the Father

In this step the person must confront and be initiated by whatever holds the ultimate power in his or her life. In many myths and stories this is the father, or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving into this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity, it does not have to be a male; just someone or thing with incredible power.

A moment before what seems like the end of the journey, Flowey appears, furious at the friendship and camaraderie being displayed by the people around him. He then reveals himself to be the king’s son, Asriel, and absorbs the souls of every single creature in the world to become a powerful and homogeneous collective of souls: the God of Hyperdeath. A terrifying, world-rending battle ensues.

Apotheosis

When someone dies a physical death, or dies to the self to live in spirit, he or she moves beyond the pairs of opposites to a state of divine knowledge, love, compassion and bliss. A more mundane way of looking at this step is that it is a period of rest, peace and fulfillment before the hero begins the return.

In the middle of the battle, Frisk remembers what they learned during the adventure. They call out to the souls within Asriel, and help each one regain their memories through the bonds of friendship that they once shared.

Then they reach out to Asriel himself, whom they discover also has a soul. In speaking to him, they help him come to terms with the grief that led to his seizure of power.

The Ultimate Boon

The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is what the person went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare and purify the person for this step, since in many myths the boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a plant that supplies immortality, or the holy grail.

Asriel breaks the barrier. The monsters, as well as Frisk, are free to leave the Underground and return to the surface world.

Return

Refusal of the Return

Having found bliss and enlightenment in the other world, the hero may not want to return to the ordinary world to bestow the boon onto his fellow man.

Frisk lingers in the Underground for a long period more (perhaps out of a sense of attachment), reuniting with the friends they made during the journey. None of the monsters leave the Underground before then.

The Crossing of the Return Threshold

The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how to share the wisdom with the rest of the world.

Frisk speaks to Asriel, now waiting to become a flower again. They reconcile with each other. Asriel asks that they leave him behind. All is resolved within this world and Frisk is untethered to return. Frisk goes back to the Barrier, and returns to the surface together with the friends they made.

Master of Two Worlds

This step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or Gautama Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds.

They discuss their future plans for life in the surface world, and Frisk accepts the proposal that they be the ambassador of the monsters to humans.

Freedom to Live

Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live.[citation needed] This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past.

End credits sequence: Characters doing what they dreamt of doing.