Since its invention, the Internet was seen as a technological marvel that truly transforms our world into a McLuhanesque global village, where information gets from one end to the other in a blink. Moreover social media made it feel like we know the things that are going on in our friends’ and families’ life effortlessly. Yet people often talks about preferring face-to-face conversation and feeling lonely despite connected. Why so? What exactly is missing from a mediated human interaction?

The Big Kiss (2008) by Annie Abrahams, live Webcam networked art, performed by Abrahams and Mark River

In 2008, Annie Abrahams created a performance installation, The Big Kiss, which invites members of the public to kiss her telematically. Their imageries appeared in the same video space, but the participants are from different geographical spaces. The “kiss”, made of a string of code and number, was transmitted through wires, transmitters, satellites, receivers, and other electromagnetic systems, before finally landing on the other pair of lips. A much bigger group of “participants” are involved as opposing to the conventional kiss, thus a truly “big” kiss.

Out of some of the most famous imageries of kiss in art history, such as Marc Chagall’s painting depicting the happy couple kissing, the photograph of Kissing the War Goodbye, one of the most daring and intense representation is the performance piece Breathing In/Breathing Out by Marina Abramovic and Ulay. By sharing their breath until the verge of passing out, they question the physical and mental limits of the human body through a kiss. Anyone who has watched the performance felt that intensity. In a rather loosely constructed comparison, The Big Kiss, in which the act of the kiss appears to be much less passionate, more gestural, almost etiquette like, came short of intensity. Perhaps, because touch, voice, and body signals, which we know are important for communication from traditional psychology, are deprived in the machine mediated experience. Indeed it feels, like how Abrahams put it, “closer to a ‘drawing à deux’ session than to a real kiss.”

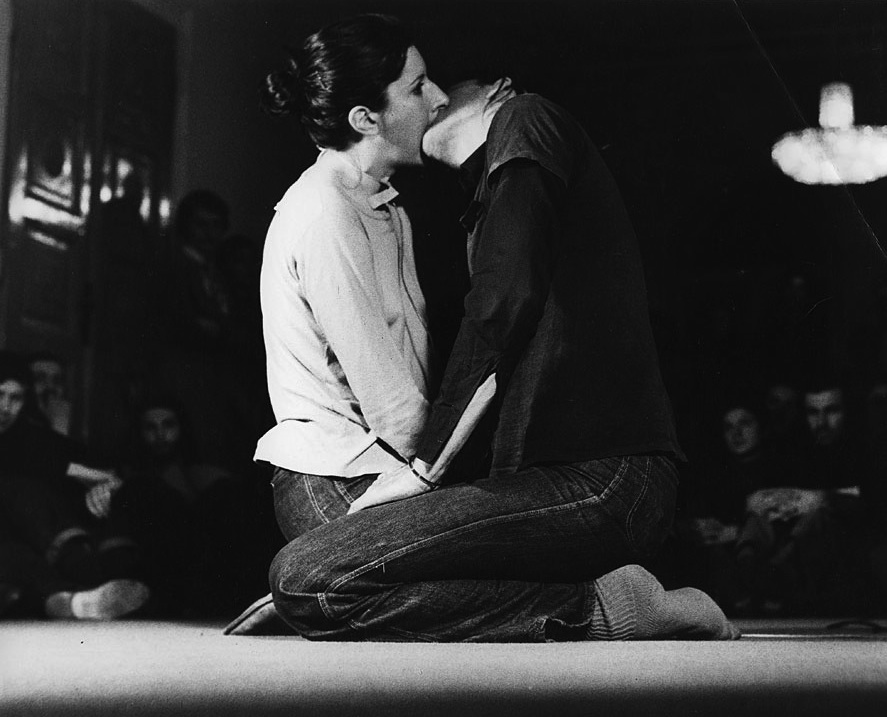

Breathing In/Breathing Out. Marina Abramovic and Ulay. 1977.

With The Big Kiss, Abrahams asks a crucial question, if the mediated kiss felt alienated for the missing of these senses, what would the disembodied human interaction lose in this machine dominated society?

Robert Plutchik, Wheel of emotions

One thing we are witnessing is the simplification of emotional expression in online communication. As seen in psychologist Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of emotions, emotions are complex conscious experience. This wide range of emotions are no where to be found in the generic response options provided, for instance, by Facebook.

Facebook reactions

Abrahams points to the same direction in the article that summarises her practise,it is likely human communication are made “easy, clean, and free of danger” to not to display the “ordinary, vulnerable and messy aspects of human communication.”

In summary, Abrahams suggests that technology at large might isolate people due to its disembodied experience and while this superconnected loneliness is experienced more and more, it is crucial to be skeptical “when people started discussing, dreaming of and glorifying the advantages of Internet collaborations“.