The means of social broadcasting have been constantly evolving, and due to the various tools involved, the purpose of social broadcasting-conveying content to an intended audience-has gone through various challenges posed by the limitations of the tools themselves. Often with the emergence of the new tools, the limitation of the old ones are shattered, but the new model has its own restrictions. As we find ourselves increasingly submitting to a world of mediating experiences, and constantly being bombarded by various kinds of social broadcasts, it is essential to understand the history of the evolution of social broadcasting so as to understand a pressing question: What are the limitations inherent to today’s social broadcasting tools?

Under feudalism, the only communication channel is a top-down one-way announcement from the ruling class to its citizens. Early forms of newspapers were born as early as the 8th Century in China, called Kaiyuan Za Bao (“Bulletin of the Court”) publishing government news.

By the 1830s, high speed presses could print thousands of papers cheaply, so what we know today as newspaper-low cost daily papers-started to appear in major cities globally.

Since then, mankind has witnessed a series of technical explosion. In the field of social communications, there are new means becoming available every decade. More importantly, these messages now reach a massive amount of audience that is unimaginable in the past. For example, The Royal Christmas Message in 1938 is allegedly heard by “four out of five homes” in England itself by radio, and in 1957, 150 Million audience worldwide since it is first broadcasted on TV.

Technology keeps progressing, introducing to social broadcasting tools like VR and immersive cinematic environments, such as Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome, that make the “suspension of disbelief” almost becoming reality. However, up until this point in history, the model of communication remains one-to-many, which could hardly satisfy mankind’s pursuit of autonomy and freedom.

As the need for self-expression grows in a more globalised and decentralised world, our social broadcast starts to embrace a many-to-many scheme. The very first attempt is by Videofreex in the late 60s, who not only aired the first private TV channel from a communal house but also made it interactive by responding to audience’s feedback concurrently by telephone, marking the birth of Citizen Journalism.

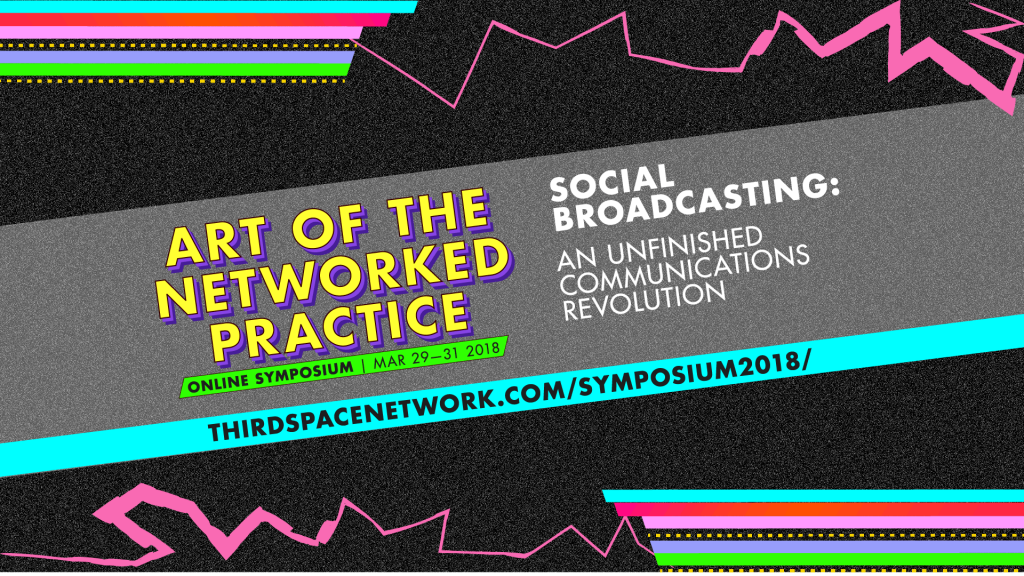

With the popularisation of many-to-many social broadcasting tools, such as social networks, podcasts, Youtube, in the face of this new democracy of social media, anyone can be a producer, sharing their stories and creating conversations with their audience. Upon close scrutinisation, we will realize the tendency of these tools expanded into becoming a “(many-to-many)-to-(many-to-many)” mechanism. This online symposium, which was hosted from the third space, inviting global participation and interaction, provided us a vigilant lookout to our multi-threaded social broadcasting model.

First of all, a multi-threaded model rejects concentration. For as long as there have been words and pictures, the people of the world have been consuming media. However the overall media consumption has immensely increased over time, from the era of the introduction of motion pictures, to the age of social networks and now the internet. This symposium took place on the platform Adobe Connect, whereby multiple conversations between hosts, host and audience, audience and audience co-exist in one setting. One has to constantly make conscious decisions as of which channel takes precedents over others, while digesting information concurrently from that channel, reserving a fraction of the brain to process the rest.

Secondly, participation is never predictable. Often in today’s social broadcasts, audience are expected to provide feedbacks and this interaction generates new content as the event unfolds. For instance, in the performance piece Online En-semble – Entanglement Training: Directed and performed by Annie Abrahams and others, NTU students are credited as collaborators for their input in the chat section. In this case, the unpredictability of the participation is favourable to the completion of the artwork. However, while the contribution from spectators are encouraged, it is crucial to be alert that it has happened a few times in social broadcasting platforms such as Facebook Live and Periscope, people committed suicide on camera after receiving assault and encouragement from online audience.

Last but not least, this multi-threaded model tends to produce more phatic expression, resulting in unwanted simplification in communication. In linguistic, A phatic expression is communication which serves a social function such as small talk and social pleasantries that don’t seek or offer any information of value. For example in the case of online communication, one can often spend too much time in meaningless conversation such as, “hello?”, “can you hear me?”, “I can hear you, can you hear me?”, “How do you do?” caused by network issues such as bandwidth, latency and the feeling of alienation. Annie Abrahams’ performance directly addresses such concern by having each performer reading out loud their network latency. Additionally, the Internet performance work, igaies, by internationally renowned Chicago glitch artist Jon Cates (US) and collaborators that took place on Day 3 of the symposium, also criticised the hyper-mediatising and phatic expression generation nature of the current multi-threaded communication today, by carefully orchestrating fragmented visuals, audios, and the occasionally dropping off and coming back of the collaborator to form a poetic performance of “small miraculous mistakes and moments of beautiful brokenness.

Drawing from historical experiences, the break-through in communication tools occurs with the advancement in technology; but the way the tools are being utilised, are anticipation made by visionaries even before the technology existed. The challenges social broadcasting faces today are immense, with rejection of concentration, unpredictability of participation, and generation of phatic expression being the top three among others. To deal with these challenges, Susan Sontag’s advice from Against Interpretation in 1966 may still be relevant.

Think of the sheer multiplication of works of art available to every one of us, superadded to the conflicting tastes and odors and sights of the urban environment that bombard our senses. Ours is a culture based on excess, on overproduction; the result is a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience…What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation, 1966

With the amount of information available to us from social broadcasting, it is time to sharpen our senses to commit to concentration, to the provision of better guidance to participation from content producers, and to promise more conversations that are cordial and substantial.

Vanessa, you make an excellent point about the “unfinished” nature of the communications revolution, or as you point out, the promise of social broadcasting. Countering your argument about phatic expression, as I understand small talk that doesn’t really amount to much, how does in fact the online viewer engage more deeply in what I refer to as creative dialogue. So you point you make at the end that I think is very important, is how the artist designs the experience to engage the viewer in interesting ways.

If you look at Hole in Space, for example, which many would consider the classic work of telematic art and viewer participation: would we consider the reaction of the audience to be phatic? If you were to read a transcript of the back and forth interaction in Hole in Space, it all may sound somewhat everyday and trivial. However, that was the point, I think. To create a free and open space for people to engage. The quality of that engagement was quite dynamic even if the what was said did not have very much useful information. It was the act of communication that was so important.

So with the chat space in the Symposium, where there was a great deal of intellectual and phatic discourse, I wonder if we can look at the quality of engagement as an important indicator of its purpose and content. Personally, I felt that the chat was very dynamic, lively, playful, active, encompassing a full range of expression.

So I think it would be quite interesting to open up a discussion tonight to examine exactly what constitutes meaningful audience participation in the context of a telematic live performance. I’m not sure anyone has a clear answer but we can certainly discuss!

Thank you for raising such important points.