Upon Kim’s suggestions on understanding the physical and social dimension of a place, I reflect on my understanding of sidewalk as a Vietnamese. This reading is particularly interesting to me because it challenges my views and understanding of the place I call my motherland.

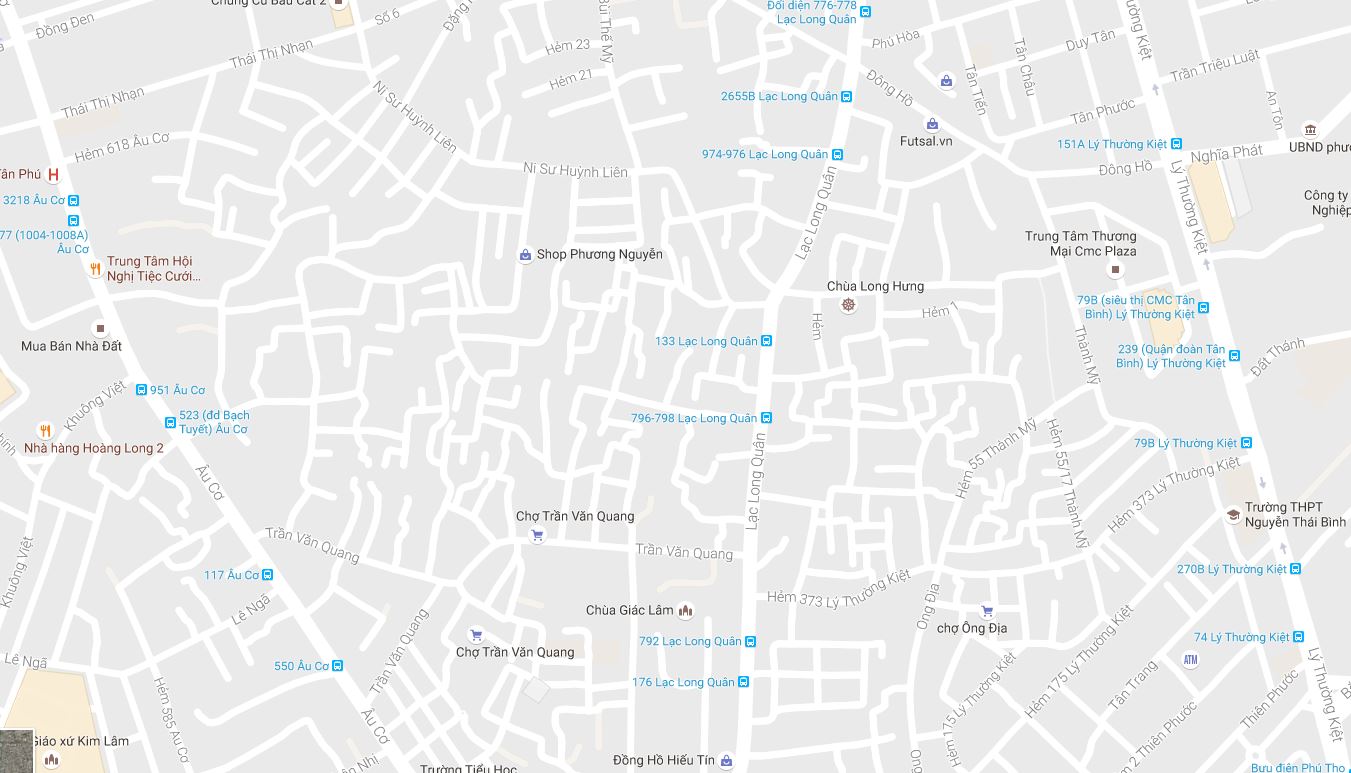

In my opinion, the commonly assumed purpose of the sidewalk as a pedestrian path does not completely apply in Vietnam.In this case, the reality of social activities does not match with the expectation of the sidewalk’s physicality that affords flow of people walking. Firstly, urban sprawling and lack of coherent planning make city roads highly complicated, resulting in long commute distance (fig1). Secondly, it also lacks public transport system such as trains and buses that usually require walking to access the stations. As such, people naturally turn to motorbikes, the most affordable, convenient and physically easy to commute between places. This might have led to under usage of the sidewalk and subsequently attracts lower income groups for other activities rather than walking. Also, the open-air and flexible nature of street vending makes it highly accessible for both motorbikes on the road (buying on the go) and pedestrians. At this point, I think that Kim’s strategy on mapping spatial ethnographies should be applied because the sidewalk is not a separate element of the city. Its dynamics are results of interactions with other elements such as the street or residential houses, economic activities in the area and its people…etc Understanding the relationships between different spatial elements will result in more informed design mindset.

Fig.1 HCMC map vs New York map (captured from Google map)

Secondly, the difficulty of policing sidewalks could be a result of cultural and moral conflicts within the mind of Vietnamese, including police officers. While many wish to see a more order and formal sidewalk that creates a better image of the city, we still linger on the cultural and emotional values of street vending. The practice of open-air market is deeply rooted in the agricultural background and clustered layout of many cities. As people used to walk long distances to work on landlord’s paddy fields and houses were far apart, it was common and logical practice to stop and buy things along the roadside. This could be the motivation for open-air markets in the past, and eventually evolves into vending carts for higher mobility we see nowadays. While post- war development in Vietnam has been radical, there is a large group of the middle age and older population who still very much relates to the society with open-air and road-side vendors. Many of those people are frequent patrons of street vending as they are used to this kind of lifestyle. Youngsters in Vietnam, no matter rich or poor, on the other hand, turns to street food as it is believed street vendors have the best-kept recipes and the food they sell is value for money. As such, while street vending could appear to be unhygienic and obtrusive, its value is not only for the livelihood of vendors but also building social fabric between classes. The questionable legitimacy of street vending is not only about its economic proposition but also emotional and social values that Vietnamese cannot deny, whether they are rich or poor, modern or outdated.

Fig.2 Patrons of street vending includes both rich and poor.

Thirdly, in Vietnam, property rights is a highly versatile concept and many times commonly agreed upon by people sharing the space, despite conflicting with proper laws by the government. Complying and resolving conflicts with the law is a strenuous and costly process which might be corrupted anyway. As such, often people sharing the space compromise and come to an agreement on how that space should be used, whether implicit by social hierarchy or explicit in the form of contracts and monetary trade. In such cases, it is a win-win situation for different stakeholders despite it being against the political regimes’ regulations and this behavior renders property rights irrelevant. For example, some street vendors act as security watchers for the neighborhood, spotting strangers, and alert crimes. Also, the idea of public spaces is not well defined and educated when it comes to pavements as compared to landmarks such as parks, library or schools. From my own experience, is many house owners assume the pavement in front of the house is theirs, and sometimes even rent it out to vendors or open up their own business. This kind of issue results from the lack of education and accessibility of information on properties rights, also the lack of transparency rather than the nature of property rights itself. While lawmakers should certainly consider ethics and inclusiveness of the law, the way the law is communicated or enforced is equally important.

The main question I have for the reading is that how do urban designer evaluate needs of different groups of people and negotiate the conflicts between groups? Also, designing and implementing public infrastructure or regulative laws is highly time-consuming and costly, while needs change as social conditions change. At some point, the original intention of a place might be irrelevant to the society it serves. How do designers then make sure the space they design is adaptable to changing needs?

Note : this reflection was originally submitted via email on Saturday 27/08/2016 due to inaccessibility to OSS. It was re-posted on 28/08/2016