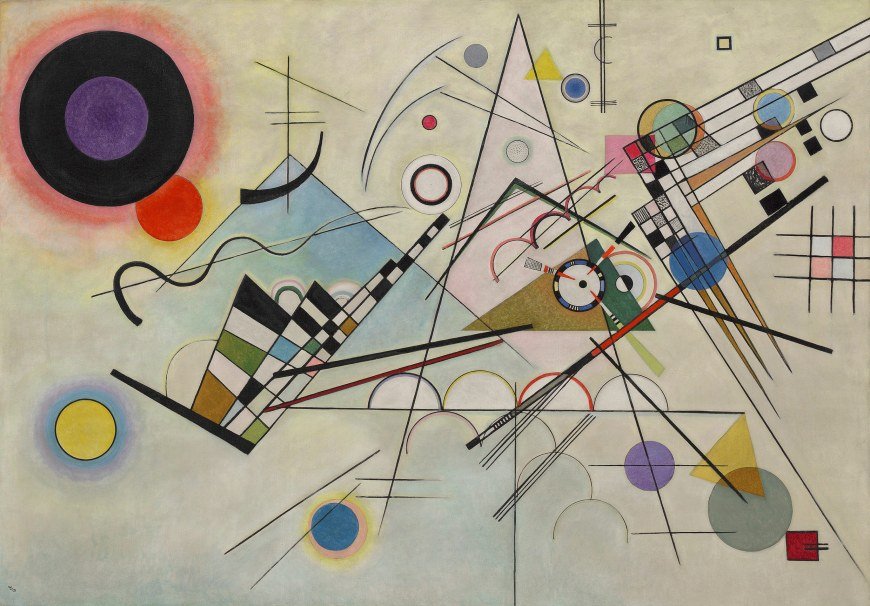

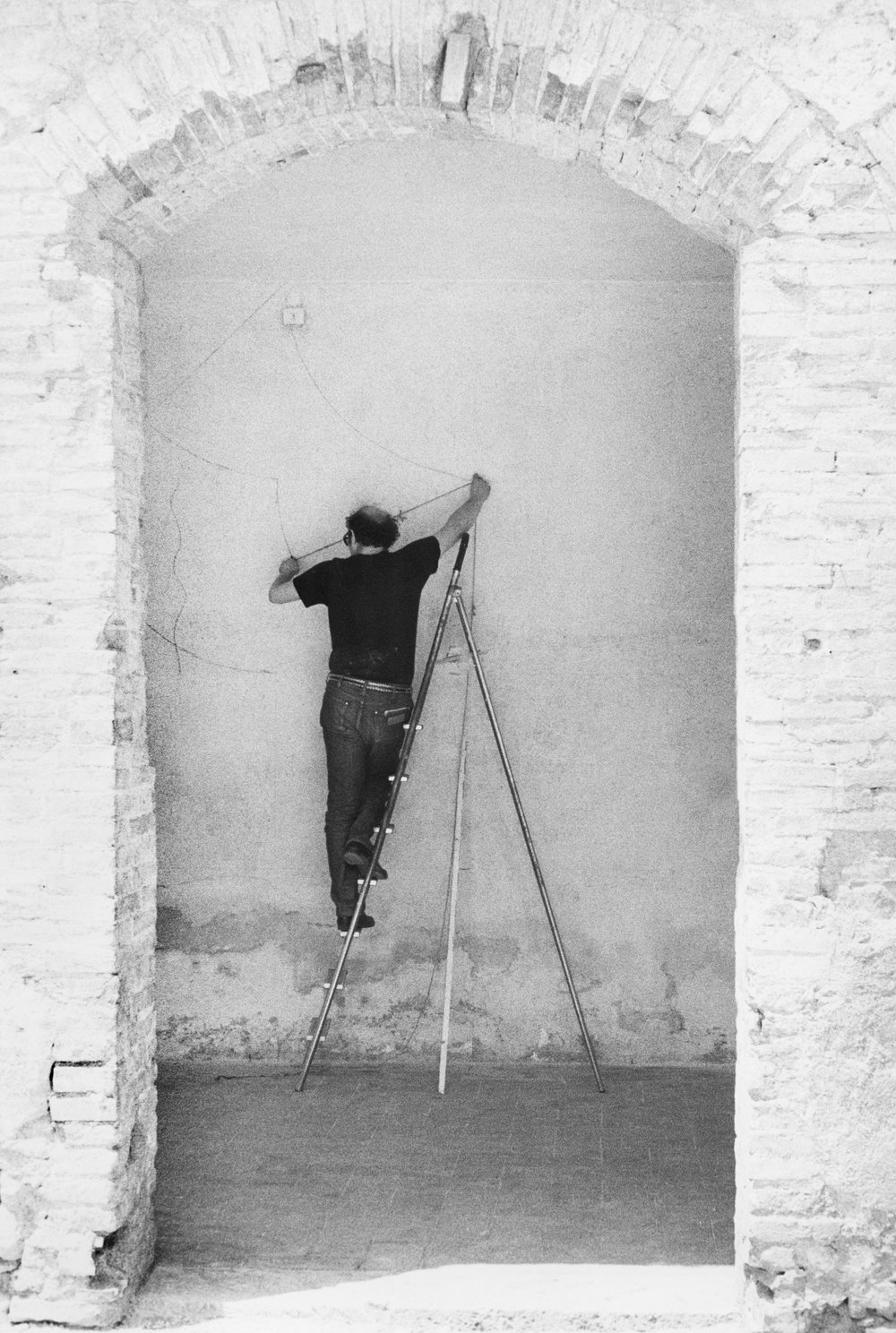

One of the ideas that i was drawn towards from the exhibition was the idea of works that are recreated by the artist studio in a space. Some of the works are recreations of the original concept which are recreated through specific instructions. The primary example would be Sol Lewitt’s wall drawings that consists of huge panels created by colour pencil lines on the gallery wall. The work required draftsman locally to carefully draw layers of coloured lines on top of each other creating a soft pastel wall of which was a spectacle in size. While I adore the idea of instruction-based installations, a few fun questions were running in my head.

the medium is not the end

Lewitt’s approach on the wall drawings was firstly to focus on the idea of communication between the artist and the audience. This idea was expressed in one of his earlier inspirations by Seth Siegalaub’s project The Xerox Book where Siegalaub invited various artists to contribute pieces to a book that would be cheaply reproduced by the Xerox machine. Siegalaub described the Xerox process as ‘such a bland, shitty reproduction, really just for the exchange of information’ . I felt this statement resonated with the concept on instructional based work of which the medium is transient and temporary. It’s just taking in form of a messenger to communicate the idea across to the audience. The importance of the work then lies more on how specific and detailed the instructions are. On how after various reiterations of the work, it’s still identical in technical execution.

the context of the space

The medium of drawing with colour pencils is relatively accessible to the common man. So if I get my hands on the instructions of one of the drawings, does the work still hold it’s integrity if i attempted to recreate it in my own wall at home? Ignoring the ideas of legal ownership and representation by recreating the work as is questions the context of the work. Would the work still communicate the same message if it isn’t in a gallery or art space? Would it still work without it’s monetary value that justifies it’s credibility as art?

recreations are always different

The curator mentioned due to the nature of how sol lewitt’s wall drawings are permanent on the gallery walls, they can’t be removed but will be painted over after. This results in each drawing being unique to the space and in such, there is no constant piece to be referenced as the benchmark. Therefore you never actually know what is the original and intended piece of the artists. This state of change in ideas are more prominent in the Trisha Brown dance pieces that I was watching a week before where the dance was restaged by local dance students. The transmission of the idea through the work is always different in the context it is staged in despite how much you can control the creation of the work. It encourages the timelessness of the piece as there is a new life to each iteration of the work, with a new collaborator or artist coming from a different time and place putting a part of them into the process.

External readings:

https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/14/ideas-in-transmission-lewitt-wall-drawings-and-the-question-of-medium