With Cecelia, Jocelyn, Nadiah and Shu, Project Social Life (name as suggested by Shu’s mother) was carried out on 14 April.

OVERALL

Password: projectsociallife. Video may be subject to later revisions.

The overarching idea is of surrendering control of yourself to others. I’ll link to Shu, who, in my opinion, effectively wrote the most concise description possible.

Viewers are encouraged to send in suggestions in response to the question of “what should we do next?”. These answers would then be compiled, with 2 options being put into a poll on Instagram: viewers would then vote which option they’d like to see. After 10 minutes, the results would be taken, and the winning option carried out.

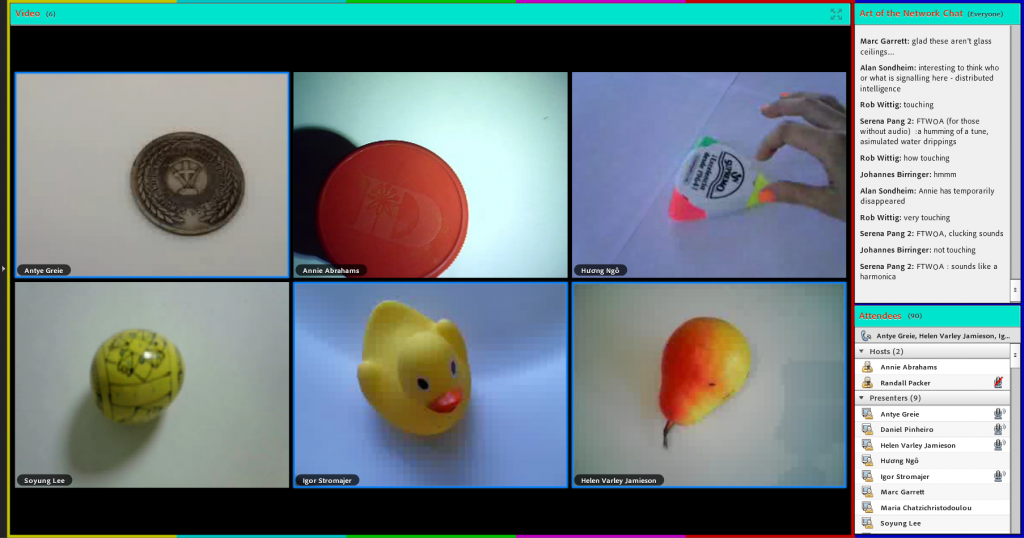

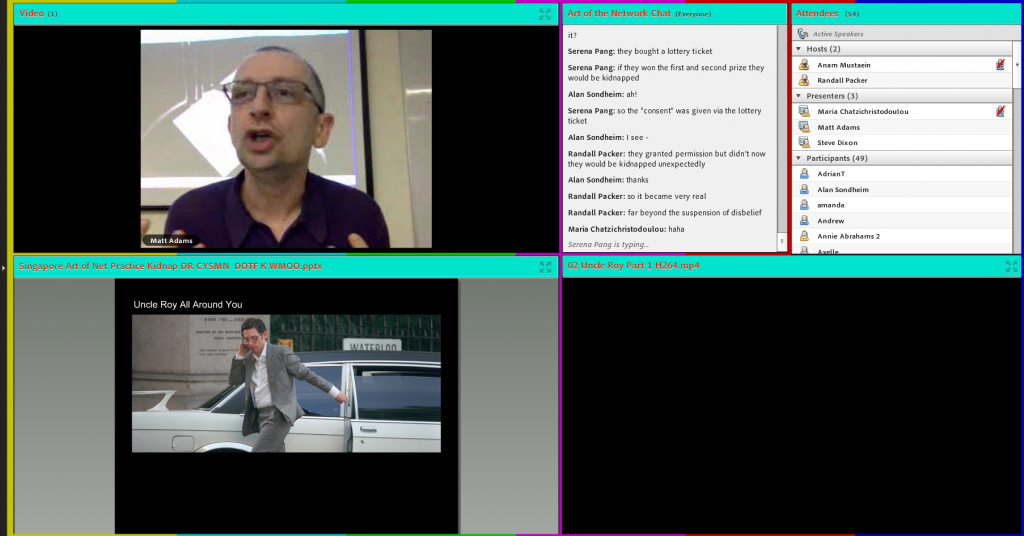

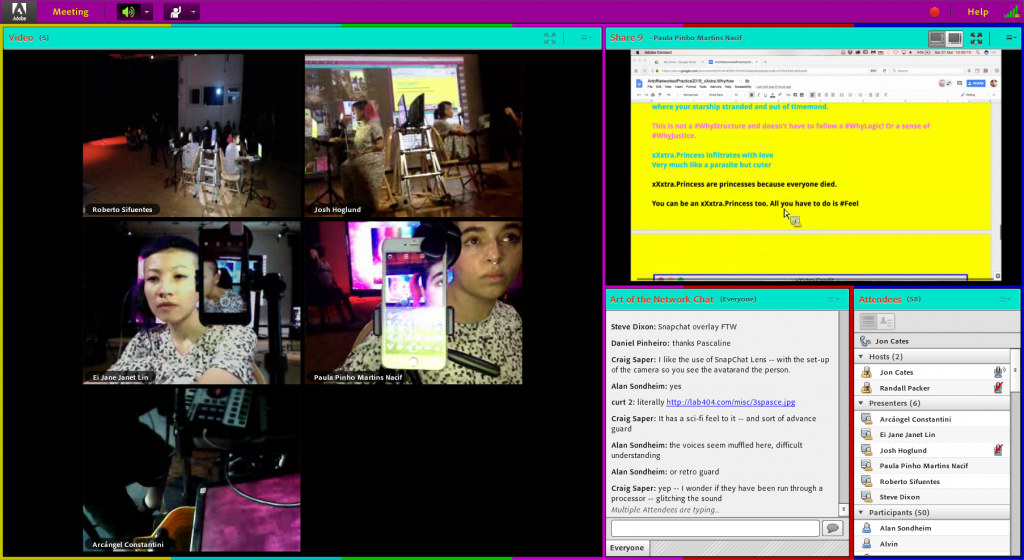

The Blast Theory style of mixing technology and physicality was employed, as was a common theme in their works, that of control and interdependence. Like A Machine to See With, there is an element of control by the external; like Can You See Me Now, there is an element of dependence on the online community. On a personal level, too, I felt that it resembles an Annie Abrahams work, in the setting of clear protocols without too much limitation on the possible inputs, leading to an outcome which may vary wildly.

PROCESS

The original idea had the same concept, but was more like this: Two teams allowing each others’ Instagram followers to control each other. While we would come up with each other’s options, viewers would vote on which option they wanted. Perhaps we would even throw dares at each other, which we’d have to complete.

Various other iterations of this concept went about, until we realised it was too convoluted, and that it didn’t particularly matter if we split up or not, or let each other’s viewers control us as opposed to our own. Additionally, it would be quite limiting if we came up with the questions and options on our own, leaving viewers to only decide the outcome.

Consequently, we made it better by relinquishing even more. The physical location and everything we did was entirely random, solely dependent on what voters in the third space wanted. No one in the first space particularly batted an eye at us, though, so unexpected elements mostly came from suggestions.

Since we were no longer splitting up, we essentially just took turns posting on Instagram, and executed orders together. On a personal level, it was difficult to know if someone else was already posting what needed to be posted, so I anticipated that we’d need B-roll shots (or at least just landscape-oriented footage, since everyone else was taking portrait-oriented shots for Instagram), and delegated myself to that.

The trailer, done by Shu, thanks Shu!, consequently featured a mix of the footage we had:

- B-roll shots (ex)

- Instagram story screen recordings (ex)

- Instagram direct message/feed screenshots (ex)

- Post-production interviews (as seen in trailer)

- Aaaand a lot of special effects and glitches

Stylistically, it drew reference from Carla Gannis (in terms of illogicality) and xxxtraprincess (girlishness).

POSSIBLE IMPROVEMENTS & REFLECTIONS

All in all, it was a surprisingly tame experience. Although we had to do various things we usually didn’t do, such as going to the arcade, there was nothing particularly intense. Personally, I feel that this might have been a result of improperly set protocols.

- We actively chose which options to present

- e.g. “go to a museum”, as opposed to “climb a tree”

- By avoiding putting wackier suggestions up, it limited the amount of wildness

- Options were often linked together

- e.g. “go to town” / “go to Boon Lay”, as opposed to “go to town” / “dance”

- By establishing a “common ground” between options, it limited the amount of unpredictability

- Assumptions were made on the context-sensitivity

- e.g. not putting up “pet a dog” if we were in a location where dogs were unlikely to be found

- By avoiding what we thought impossible, it limited the notion of being forcefully controlled

- Only major decisions were decided by viewers

- e.g. heading to locations, doing certain things

- By not letting viewers control every single detail, we still retained freedom

In a sense, we weren’t supposed to enjoy ourselves, but did anyway, because we still retained a rather large degree of control. For example, it would have been interesting to see us have to execute an order even if it’s difficult or humiliating. (It’s not impossible to be told to pet a dog while on the train. Just alight, get out, and run around till you find a dog. Painful, but possible.)

Alternatively, it would have been interesting to see us being utterly controlled, not just in terms of being told where to go, but also every single detail. This might seem masochistic, but what if we couldn’t even do anything unless we were instructed to? If no instructions come in, we’d have to just stand there, staring at our phone, until someone says something. If we’re not told to, we can’t ever wipe our sweat, or rub our eyes, or breathe.

Of course, this didn’t happen, which is an interesting phenomenon.

Even when told to control someone else, we form assumptions as to what degree of control we can have. No incredibly specific suggestions came in, nor illegal suggestions. Even when we thought we had relinquished control of ourselves, we ourselves assumed a degree of freedom. We went to the washroom without being told to, PLAYED at the arcade though we were only told to GO to the arcade, etc. And no one questioned our freedom to do that.

In any case, though, I still think that we were able to bring out that idea of being controlled, where the artists become the puppets of the community, although only when the suggestions didn’t clash with our natural instinct to protect ourselves. In fact, the blatantly obvious protective measures make an interesting statement on self-preservation and assumed freedom as well.

(On a related note, I am compelled to recommend On Liberty as a good read on the relationship between authority and liberty.)