18 Points of View: SPACE

SPACE from the point of view of an astronaut is uncharted waters.

SPACE from the point of view of a passenger is that which leaves to be desired.

SPACE from the point of view of an alien is its normal habitat.

SPACE from the point of view of a plant/ nature is opportunity/territory.

SPACE from the point of view of a bubble is its existence (or is it?)

SPACE from the point of view of a designer is a canvas.

SPACE from the point of view of a performer is a stage.

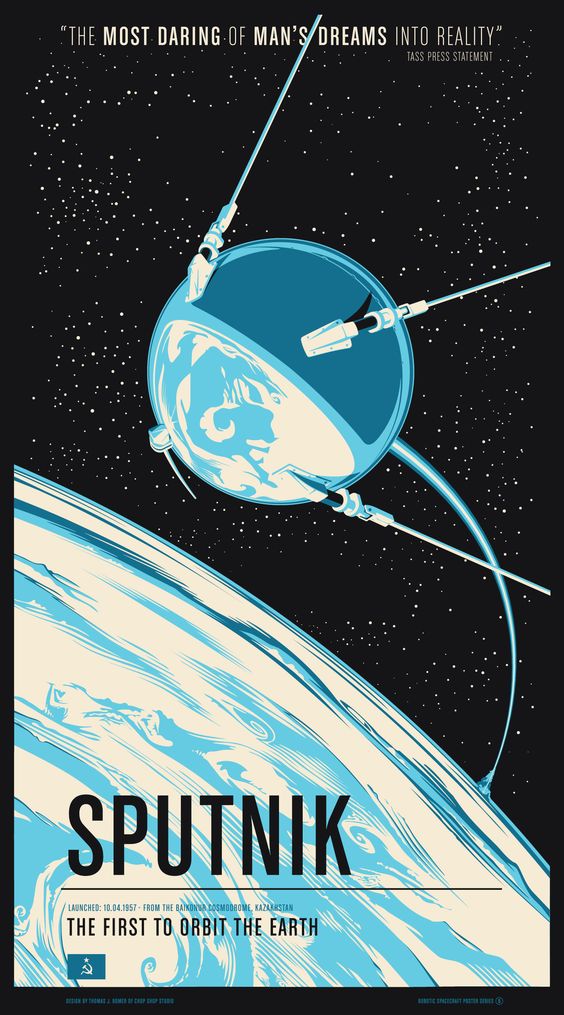

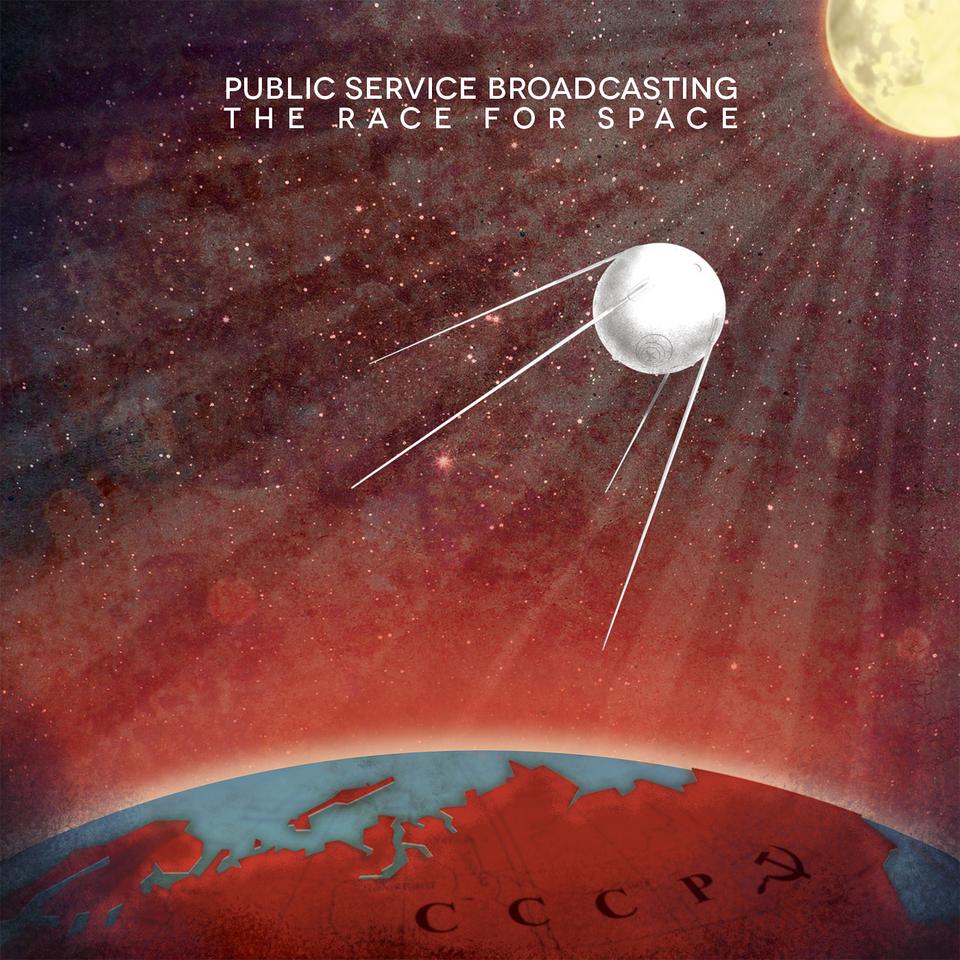

SPACE from the point of view of history is political (space race).

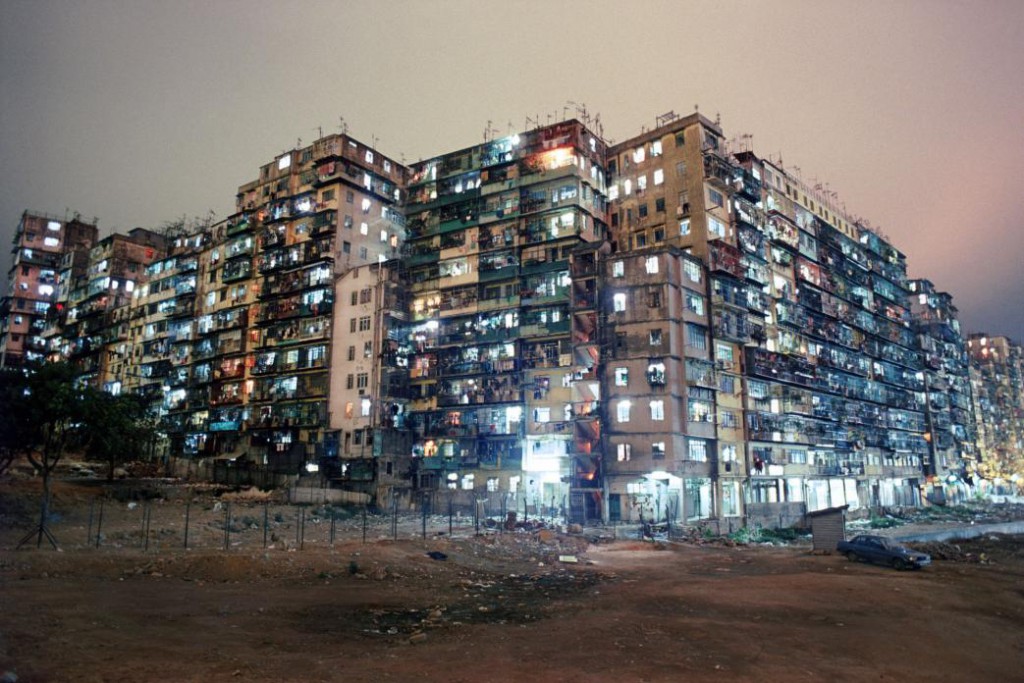

SPACE from the point of view of Kowloon Walled City is impossible.

SPACE from the point of view of a wormhole is non-existent/ irrelevant.

SPACE from the point of view of me is consciousness (headspace).

SPACE from the point of view of strangers is comfort.

SPACE from the point of view of music is a break.

SPACE from the point of view of Michael Jackson is a walk (in the park).

SPACE from the point of view of Star Wars is a setting.

SPACE from the point of view of a clock is time.

SPACE from the point of view of a child is fantasy.

SPACE from the point of view of Nietzsche is the void.

SPACE from the point of view of a key board is the space bar.

SPACE from the point of view of teeth is a cavity.

SPACE fom the point of a city is a luxury/expensive.

Visual references

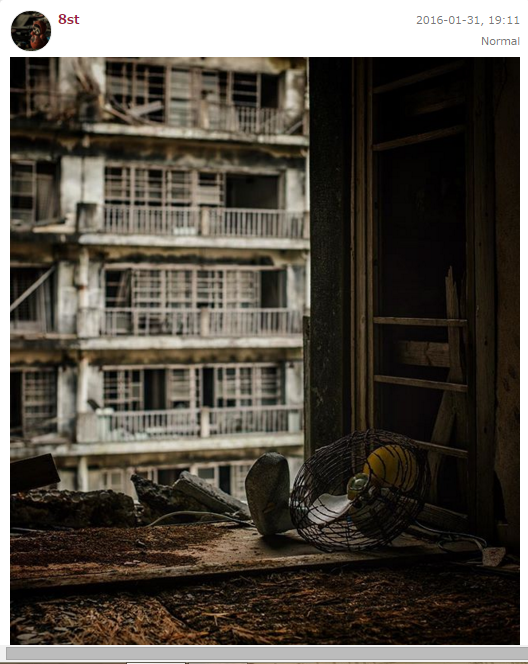

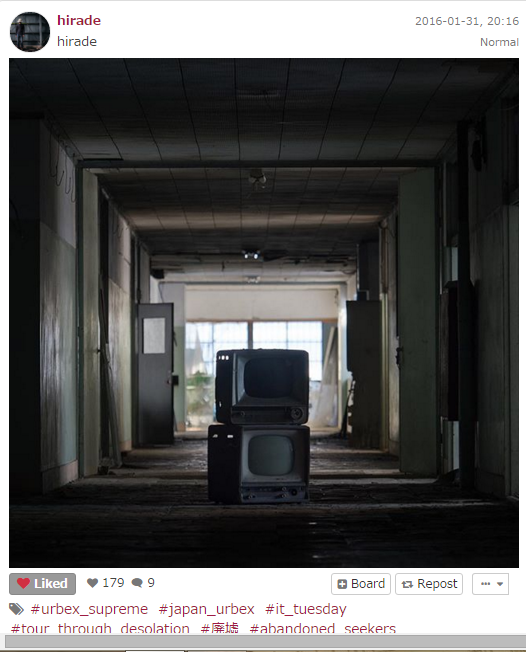

On spaces: Interesting/ abandoned spaces in urban dwellings

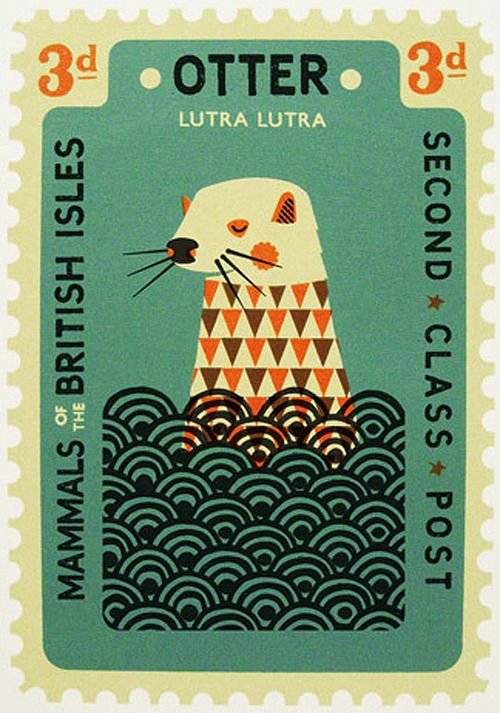

Vintage Graphics

Album Covers

Other visual references

Focus on:

illustrative style

narrative in the composition

minimalist/emptier compositions – giving space

muted/ controlled colours