Tag Archives: essay

Protected: Cadillac Ranch: A Pop-Art Stonehenge

[EI] Telematic Dreaming and the Third Space

Randall Packer asserts that “The laws of the known world have been all but abandoned in the third space: it is a space of invention and possibility.” Indeed, Telematic Dreaming brings two people, thousands of kilometers apart, together. While it should not be possible that they would both be able to interact with each other simultaneously in a shared space, Paul Sermon makes this possible through the usage of the ISDN network and the Third Space.

What is most striking about watching a video of the installation is how aware the audience is that they are on a bed whilst interacting with the artist. The connotations that being ‘in bed’ bring do not go unmissed. As a space in which we sleep and be with our partners and loved ones, the gestures between the bedmates are tender and intimate: we witness this from the 2 min 50 second mark in the video below.

With the work having been exhibited in the 21st century since its conception (most recently in 2011), it is not a far reaching statement to assume that the audience would be well acquainted with the third space. As Randall Packer writes, the “digital natives”, a group that the audience is part of, “are the standard bearers (of the third space)”. With all the (possibly unknowing) familiarity with the third space, it is interesting to see how the audience member reacts to this third space.

The user physically inches away when the artist makes sweeping motions across the bed, like they are almost scared to intrude on that space, even though they most definitely, physically can.

The artist then moves to the right side of the bed, and the audience member takes the opportunity to scramble to the left side (lest the artist start making sweeping gestures again, I believe). Even the psychedelic background of the projection does not take away from how real it is. In fact, coupled with the trance-like music playing in the background, and the fact that the participants cannot audibly communicate with one with another, the whole situation becomes almost too real: the experience of laying in bed with a projected person, next to you becoming heightened.

Moreover, we take note that this action of laying in bed need not be physical – as the artist himself writes, “the user exchanges their tactile senses and touch by replacing their hands with their eyes”. This begs the question: Can we feel through our eyes? With the above analysis, I would say that we can, to an extent, at least. We cannot physically do so, but we can materialize what we see as the feeling of being touched. This translates into our everyday lives – we feel a rush of happiness when we see our loved ones, and feel frustrated when we see what we planned for not working out. Subscribing to Cartesian Dualism, I would say that immaterial reality manifests in the virtual body that the artist projects in ‘Telematic Dreaming’.

Sources referenced:

- Packer R. “The Third Space,” (2014) in Reportage from the Aesthetic Edge

- http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/staff/sermon/telematic-dreaming

- http://v2.nl/archive/works/telematic-dreaming

- https://www.digitalartarchive.at/database/general/work/telematic-dreaming.html

- https://www.leonardo.info/gallery/gallery332/sermon.html

[EI] Open Source: An Introduction

We had our first experimental interaction class today! I decided to record down my notes from class and conduct some further research on the works we discussed, as Mr Packer mentioned that Cut Piece was a classic (it was mentioned again in the reading he gave us).

What we discussed in class

Yoko Ono – Cut Piece (1964)

- The artist gives up control of the work – as a result, the role of the artist and viewer are reversed.

- The work could be a commentary on women being objectified, and the male gaze.

- How is the work social? It requires the active participation of the audience. The role of the artist and audience is reversed, in a sense – the audience takes on a much more active role than Yoko Ono, who sits passively (although her facial expressions do show how uncomfortable she is with how aggressive the audience is towards the end of the piece)

- DIWO in the sense that the audience is doing it together, taking turns, and having a collective experience

- Indeterminate: the piece is indeterminate in its outcome; you could have a rough idea but don’t know what exactly

Jenny Holzer – Please Change Beliefs (1997)

- Art that requires the internet

- The role of the artist is to be a designer of interactivity

- The content of the work? Language, words, and communication

- Space is global, not confined to a room, hence encouraging global communication

- In terms of time, it is available 24/7

- This piece also led us to a discussion about The Third Space, in which the local and remote can be together in a shared network space e.g. on skype, or the telephone.

I did some reading up on Cut Piece, too. The work remains a key piece within the Fluxus art movement due to how it engages with an artist’s body, as well as the way in which it mirrors life – with an obvious political gesture. I found that by the audience being implicated in the (potentially) aggressive act of revealing the female body bit by bit, Yoko Ono further challenges the neutrality of the relationship between viewer and art object. It does, in fact, depend on the audience’s willingness to participate – something to think about for my future projects, I guess – it’s important to consider how the audience would receive certain instructions as well.

In preparation for the essay, I printed the readings out, annotated them, and summarized them into this Google Docs document: do check it out for a summarized version!

Assignment 1

Sida Vaidhyanathan gives us an overview of the history of the proprietary model from the 1970s. Software vendors asserted control over their source code – Richard Stallman, in response to this, established the Free Software Foundation to fight for software rights to protect hackers and open source enthusiasts. Linux and the World Wide Web are other projects that arose from a community working together – prime examples of peer production.

The first minute of the above video explains why Linux, for example, is preferable to the proprietary model, which tends to be a closed system. Indeed, the strength of peer production lies in its matching of human capital to existing information such that new information can be produced – “(exploiting) human capital as opposed to monetary capital”.

Sida Vaidhyanathan mentions that the proprietary model asserts that innovation would not occur without monetary benefits, and that “fencing off” innovations is vital for firms to establish markets. A negative aspect of this would be that this model locks in the advantages that technologically advanced states have over less advanced ones, creating a stagnant culture.

Open source encourages the opposite of this, as discussed by Randall Packer. He writes that “Open source way may be viewed as a quasi-utopian form of peer production that inspires transparency, collaboration, collective process”.

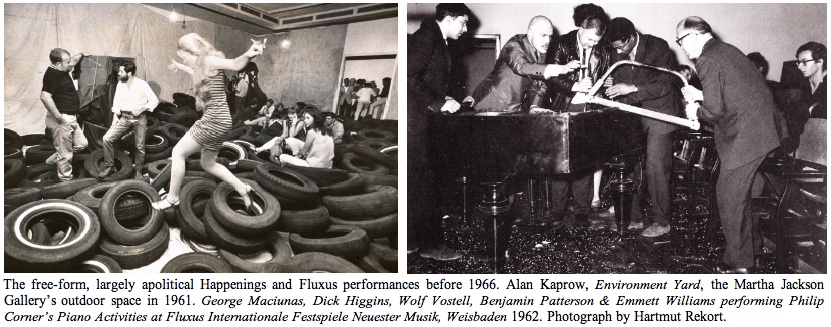

An important concept in the history of open source is the evolution of the gesamtkunstwerk (total art), found in 20th century Art avant garde movements. Allan Kaprow as part of the Fluxus pioneered performance art through the “Happenings”.

The “Happenings” integrated all forms of media, action, gesture, spoken word, and artifacts. Decentralization of authorship, location, and narrative unstratifies forms of interactive media that expand and reorient the boundaries of time, space, viewer and artist to create new kinds of collective experience and social engagement.

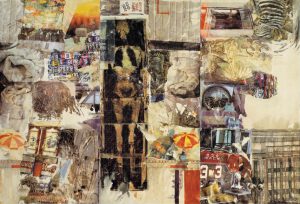

The discussion of open source need not be limited to peer production. “Open source” techniques, such as appropriation, freely borrow from mass media. Its history is long, starting with Robert Rasuchenberg, who overlapped appropriated newsprint with painting and drawing.

Rauschenberg made mixed media collage work, using silkscreen process to overlay appropriated newsprint with painting and drawing,

Soon after, Nam June Paik used appropriation for his video work. More recently, the web has made it easy for artists to appropriate online materials. For example, Mark Napier’s The Shredder used the web as a vast open source archive.

In relation to open source thinking, the collective narrative is an open exchange leading to creation of voices. This can be traced back to the 20th century avant garde, for which social interaction was essential, for example, the Exquisite Corpse Surrealist game. More recently, the concept of trending (and social media sharing), whilst not a traditional narrative, is another type that is “compressed, often playful and multithreaded”.

Possibilities of peer to peer authoring of the collective narrative manifest today with Google Docs, Microsoft Word, and WordPress, all of which differ from the traditional act of writing with their potential to collectivize writing, which is often an intimate act on its own. Furthermore, they make it publishable, worldwide, immediately.

The open source model has expanded into other realms – the music and scientific spheres have attested to their commitment to openness with cultivating open-access journals. Programming, today, also often takes collaborative forms such as DIY events, hackathons, maker fairs, residencies etc.

440 words (I really tried to make it 250 words, I really did)

Other references:

http://uk.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2015/may/18/yoko-ono-s-cut-piece-explained/

https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/yoko-ono-cut-piece-1964

https://images.huffingtonpost.com/2011-12-28-2Happenings.jpg