DIWO and Artware

“As an artist-led group, Furtherfield has become progressively more interested in the cultural value of collaboratively developed visions as opposed to the supremacy of the vision of the individual artistic genius.”

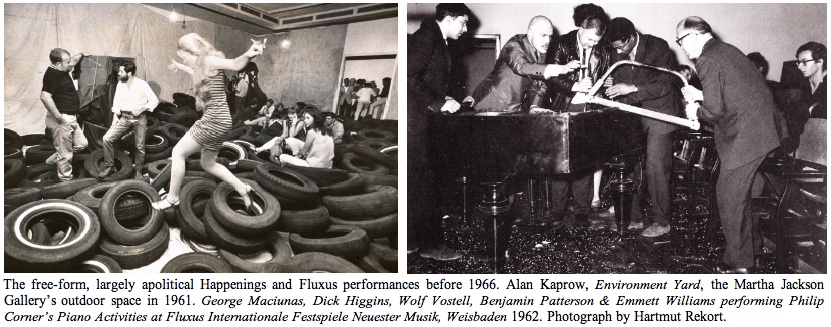

During the lecture, Garrett makes an indirect reference to this quote when he brings up how maker culture pushes creatives out of their comfort zone. Painters need not just work with painters, or media artists with media artists. He supported this with the example of how Picasso and Braque founded Cubism by looking at each other’s work. Another example that I could think of would be how Matisse and Derain, together, formed the basis of Fauvism. He is very for the narrative that an artist cannot just be an isolated genius. As with these gigantuan founding artists of indisputably important art movements who have worked together, it is intriguing to think that DIWO does have historical roots in these movements. Today, DIWO has taken on a new life and meaning with the advancement of technology.

This technology, here, would refer to a unique creation by Furtherfield: “artware”, which are software platforms for developing art that “rely on the creative and collaborative engagement of its users”. Unique “artware” created by Furtherfield include FurtherStudio and VisitorsStudio. This essay goes on to discuss projects that have come to fruition with the agency this artware brings, and how they relate to the concept of DIWO.

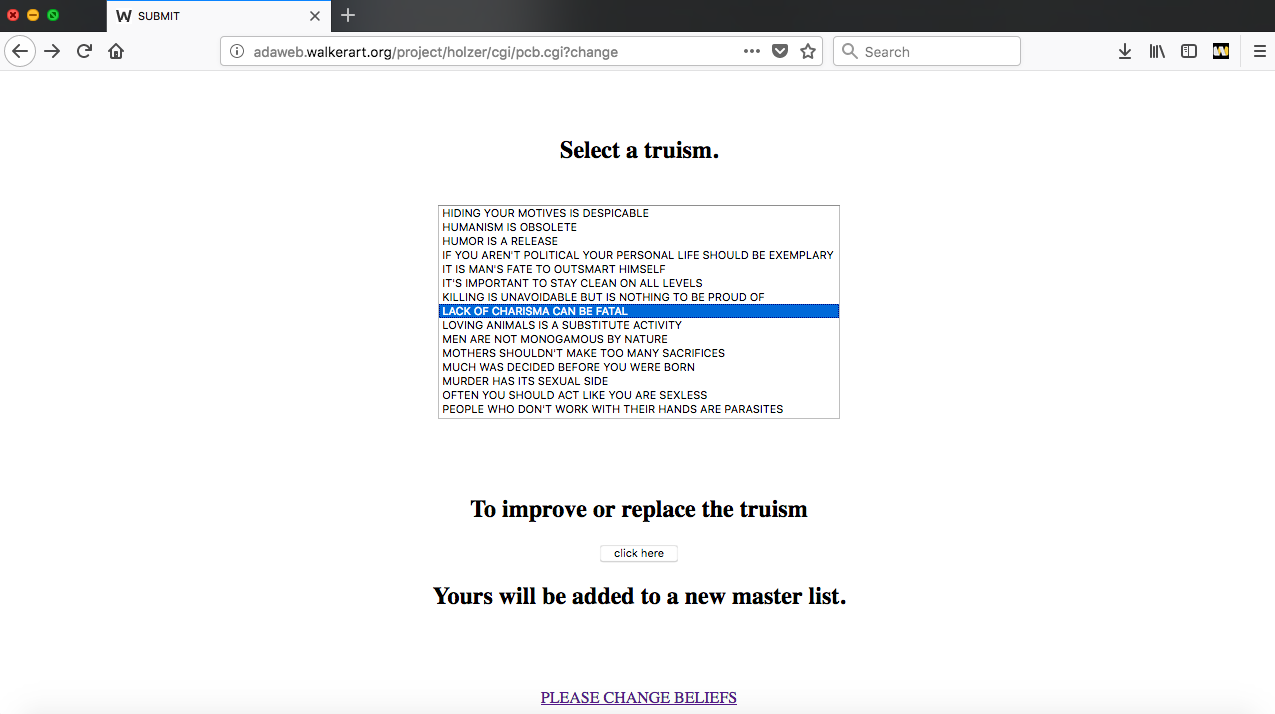

Of course, artware need not be specifically limited to that which Furtherfield has created – another example that would fit the criteria of “artware” would be the website built specifically for Jenny Holzer’s Please Change Beliefs.

Please Change Beliefs had a specific software platform built especially for users to modify truisms creatively and vote on truisms they agree with; in doing so collaboratively, DIWO is also brought to mind.

DIWO and the Third Space

In March 2006, 150 (Furtherfield) media arts projects took place in over forty London locations, as well as online in the form of exhibitions, installations, software, participatory events, performance-based work, and many other self-defining forms (from page 24, Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett “Do it With Others (DIWO): Participatory Media in the Furtherfield Neighborhood,” 2007)

Its structure was inspired to some extent by the scale-free networks of the Internet, which, the science of networks tells us, maintain high levels of connectivity regardless of size.

Here, the importance of the Internet and all the connectivity it has brought to us cannot be overlooked in the benefits – specifically, convenience – it has brought to DIWO. For example, the use of the internet in the Tele-Stroll micro-project, as well as Telematic Embrace project, enabled us to Do It With Others – a partner for the former, and a much larger number of 18 people for the latter – and create beautiful and innovative outputs we could not have done alone.

DIWO and Ownership

“BritArt’s dominance of the 90s UK art world-its galleries, markets and press-with a small number of high profile artists, delighted nouveau toffs but disempowered the majority of artists.”

DIWO supports the theory that there are no “supreme” artists, ala BritArt. This ties in directly to Open Source Thinking, where peer production leads to a multitude of talents working on a project, such as Linux. (See here for technological manifestations of peer production in an earlier essay).

Marc Garrett mentioned a piece that was particularly relevant to this section. Plantoid is a renewable, blockchain-based lifeform.

After scanning QR codes with mobile phones, the plant is fed with digital currency. Upon massing enough, it “enters into the reproductive stage”, in which artists physically make a plant (with instructions given). What is interesting here is that the artist does not have full control over the work – he or she follows a “contract … that stipulates the rules”. Another aspect of DIWO that we wean from this work is the concept of giving up ownership of the work.

Closer to home, we personally gave up ownership and collaborated with the Exquisite Glitch project.

In the same vein as its namesake, Exquisite Corpse, we continued glitching over an initial image consecutively in our groups. Here, no single person claims sole authorship over the final product; as a collaborative DIWO effort, all the group members claimed equal stake.

DIWO and the Collective Narrative

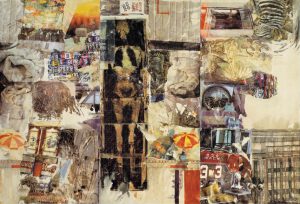

The collaboration we observe in Doing It With Others enables us to not only give up individual ownership. This collective ownership enables the co-curation of the artwork, breaking down the power relationships between artist and curators (to be discussed further in section below). What becomes a direct product of this is a collective narrative that could not have occurred with a singular person curating the work – the diversity that could not have come from one person’s thought process alone is what makes the collective narrative such a visual pleasure to look at.

The shift from material to immaterial culture, and the explosion in the rate of copying, duplicating and redistributing of cultural artefacts, means that this culture is now open to the influence of not just ‘professional’ cultural producers.

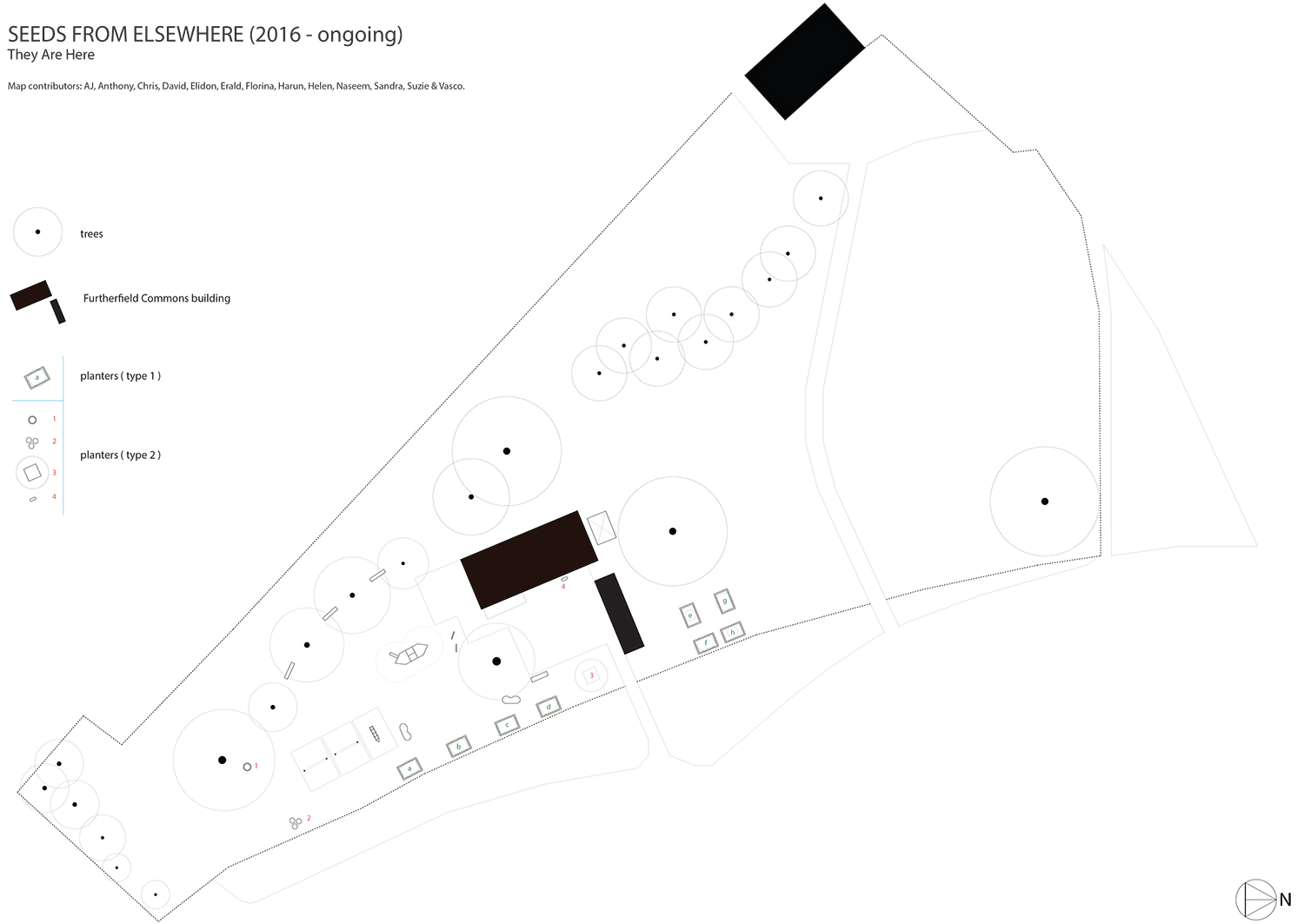

Another point that this quote brings up about the collective narrative is this narrative is now open to the vernacular as well. The Furtherfield work, Seeds from Elsewhere, is a prime illustration.

In his lecture, Marc Garrett mentioned that the project arose out of the interest in understanding the cultures of refugees living in the park. What conversations could arise? The project formed a collective narrative in the various different plants and produce grown, “contributing to a horticultural portrait of the group”. As an organization interested in grassroot culture, this project was socially conscious in being decisively inclusive – which Garrett mentions being an important quality – and not just art for the market.

DIWO and the Power Relationships

Between Artist and Viewer

VisitorsStudio, created in parallel to FurtherStudio, “gave visitors an insight into some of the artistic processes and concerns of resident artists by creating a social space online where they could experiment and learn together using some very simple audio-visual media mixing tools.”

This breaks down the hierarchical relationship between the artist and the viewer, instead, placing the role of the artist as mediator so that both artist and viewer could DIWO. By providing a creative space that connected more experienced practitioners with novices, Furtherfield supports learning on both ends. Another example of this would be Cut Piece (see here for notes on Cut Piece and DIWO).

Between Artist and Curator

Maker Culture breaks down the power relationships between the artist and curator, as well. We see this exemplified in the collaborative exhibition put on by Gretta Louw and aboriginal artists from Australia, mentioned by Marc Garrett in his lecture.

These Warlpiri artists could not get curators and galleries to show their work in the UK, but Furtherfield worked together with them to put on a media art exhibition, a first in the UK. Here, they took over a space that showed their own artwork on their own terms, and have come to exhibit in other countries like Germany and Spain.

We, as students, get a taste of this co-curation with the Collective Body project as well. Source: https://www.flickr.com/groups/2128661@N24

DIWO and the Open Source Thinking

The fact that Furtherfield’s core activities (“of review, criticism and discussion”) have been sustained by its team, and its international group of users, on a mainly voluntary basis, truly encompasses the spirit of the open source model that I have written about previously. Indeed, the strength of peer production lies in its matching of human capital to existing information such that new information can be produced – “(exploiting) human capital as opposed to monetary capital”.

Open source encourages the opposite of this, as discussed by Randall Packer. He has written that the open source way may be viewed as a quasi-utopian form of peer production – it is amazing to realize that this utopia has actually manifested in such a tangible way in Furtherfield. It then becomes not such an unrecognizable ideal, but a reality that we are able to access.

It is even more impressive is that Furtherfield has grown from a humble network to even receiving regular core public funding for some of its work. Furtherfield holds agency, here, which is what creators (myself included, as an art student), aspire towards one day. Open source culture need not be one that is viewed as against status-quo (as it has been historically) and that status quo can even come to support it.

DIWO and the Future

It was fascinating to hear about how DIWO has been taken even further, and interpreted incredibly differently, in the Blockchain community. Marc Garrett mentions that after the major bank crash in 2008, people explored other means that were less dependent on specific economies.

A brief overview of Blockchain: Blockchain is a decentralized database secured by different servers. Now, it is used to make art as well. As a very young piece of technology (around 10 years old), Blockchain is still a mystery to many people. For comparison, Marc Garrett specifies that the Internet has been around since the 60s, whilst the World Wide Web has been around since the mid 80s. Evidently, there is much potential in Blockchain, and artists have much to explore.

Back to Blockchain and DIWO, it is incredible to see how people have come together to create entire communities. Marc Garrett mentions that in Barcelona (and other countries), 600 people have created their own country, and alternative economy with their own currency, Faircoin. This very strongly reminds us of Linux and Open Source Thinking, where undoubtedly, a number of people would have collaborated to create an entire community on their own.

He also mentions that China is setting up workshops around blockchain because of what it can do for communities – in the future, this could definitely create real alternative physical communities. In this sense, blockchain is not just seen as new economies, but as an entire Renaissance occurring, even more so because these technological tools carry with them the possibility to make art, not just money.

Marc Garrett also mentions that Furtherfield is going to work with Fair Co-op, and is thinking about making a currency for Furtherfield called the Culture-coin, purely for interaction with one another as part of Furtherfield. This is a very DIWO concept – this is about pulling everybody up with one another and creating a fairer society, and art.

Word count: *sweats nervously*