[On Social Broadcasting: A Communications Revolution]

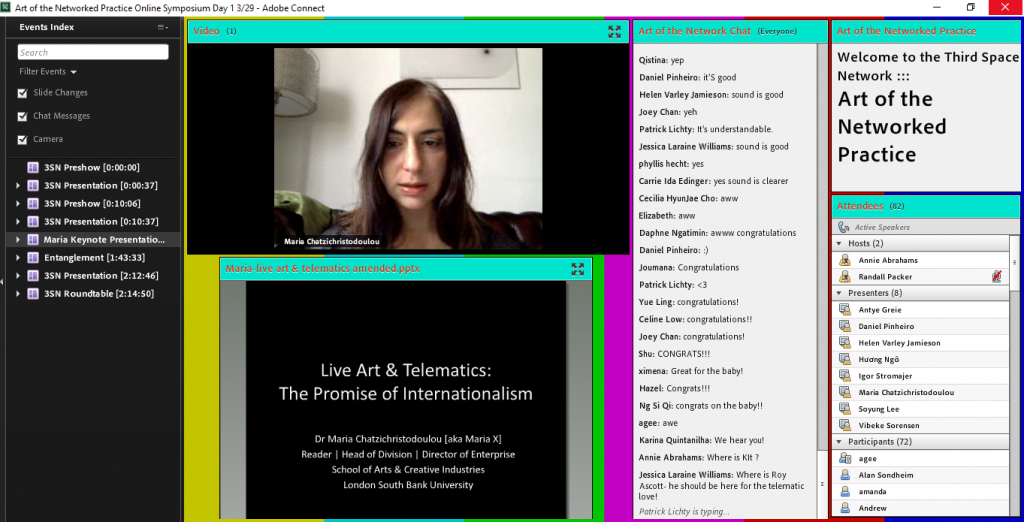

|| During the Art of the Networked Practice 3-day (or night) symposium that took place from 29th-31st March 2018, I got to listen to very insightful speakers and witness before my very eyes how far art has grew simultaneously with technology. It is amazing to think how unfathomable all of these works would have been way back when the social broadcasting tools and platforms were just made available.

https://videofreex.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/img_2520.jpg

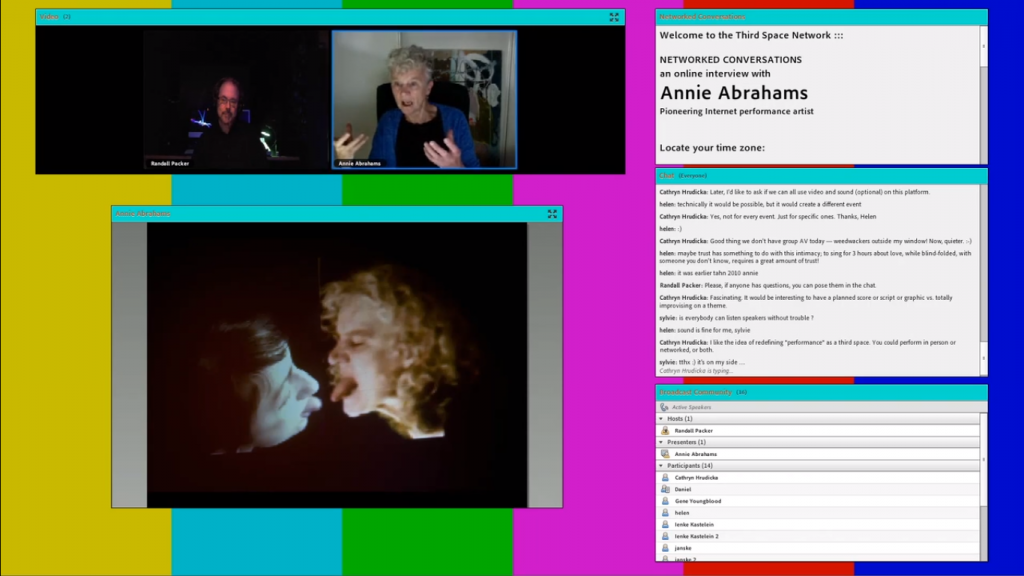

Since then, social broadcasting has been used as a medium by artists to explore how communication and interaction between people can be altered through it. Annie Abrahams mentioned about how this change is not necessarily better or worse, but rather, just different. In her keynote speech, Maria Christochatzidolou (MariaX) questions the development of social broadcasting art by sharing a myriad of examples of works that use social broadcasting to push the boundaries of art even further.

For one, social broadcasting changes the way we perceive interactivity.

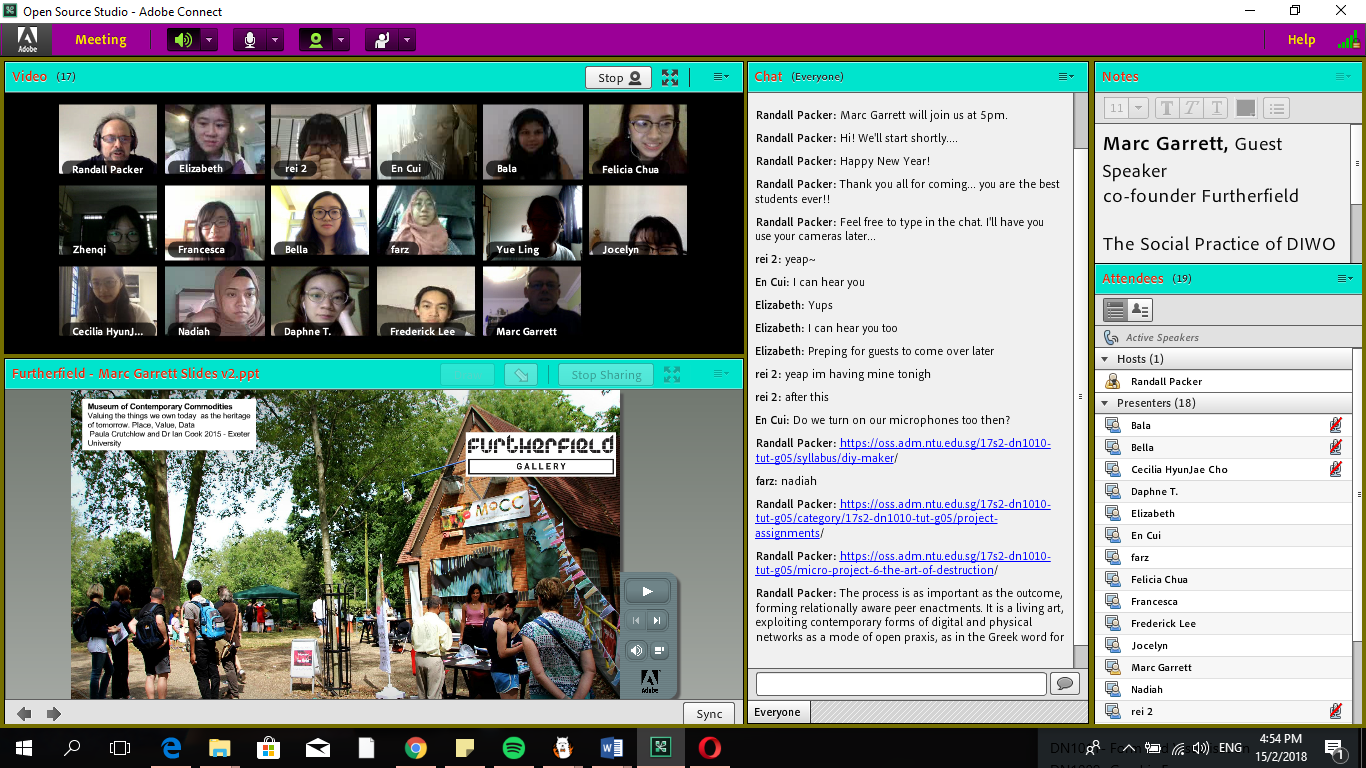

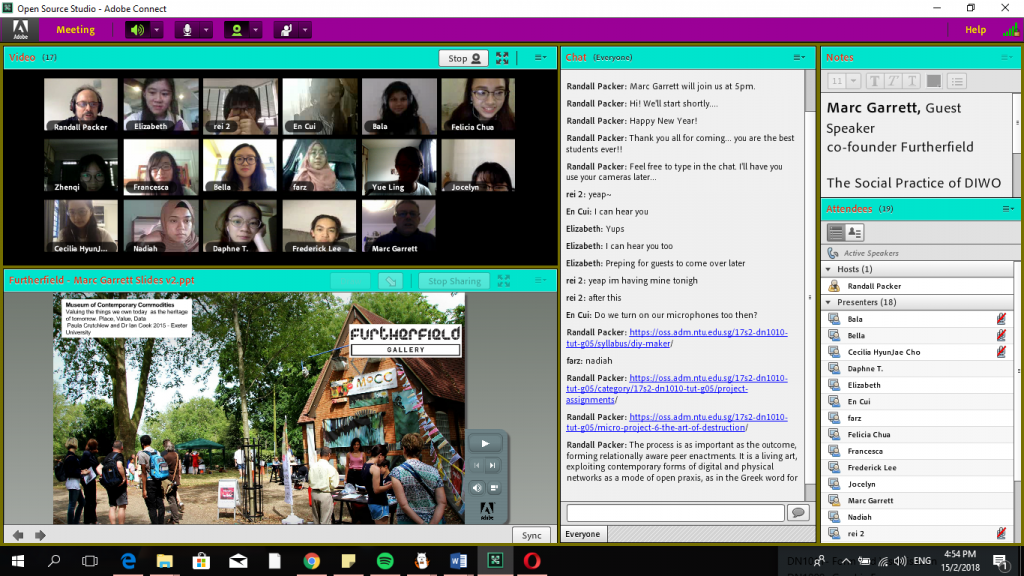

MariaX introduced the concept of the use of technology to bring people together into the same ‘Space-time continuum’, where people can transcend geographical boundaries and be brought together over the metaphysical ‘Third Space’ (coined by Randall Packer). This greatly enhances the opportunities for collaboration and allow more artists to practice the art of Do-It-With-Others (or DIWO), advocated by groups like Furtherfield and Blast Theory.

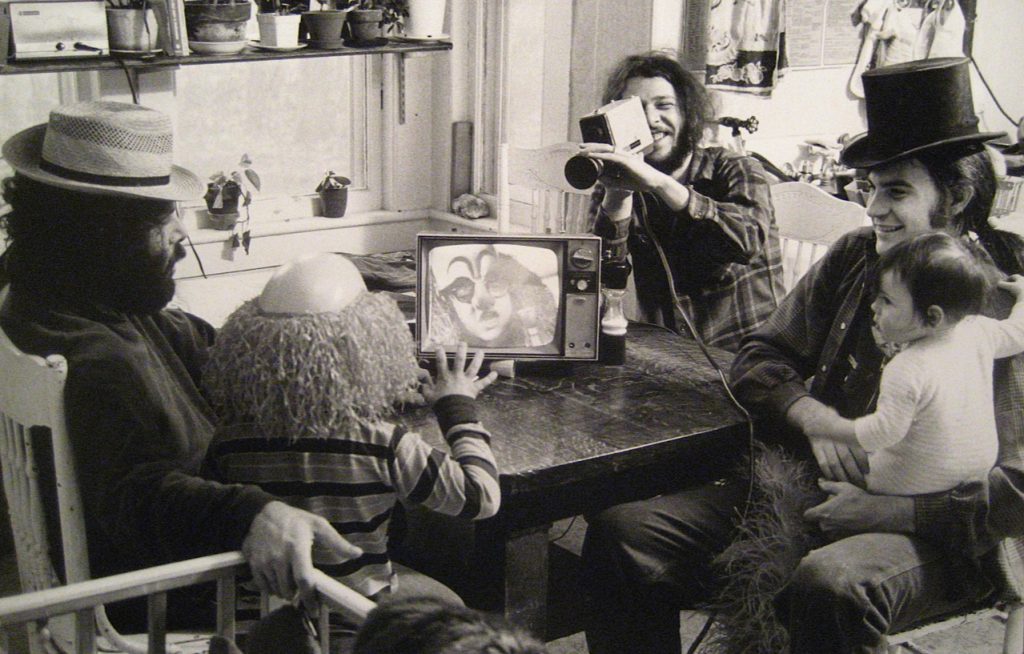

Together with DIWO came the concept of giving up the ownership of the performance partially, if not fully to audience members, such that they had the power to influence the outcome of it. One example of this is Kit Galloway’s and Sherrie Rabinowitz’s ‘Hole in Space’, which was part of their satellite art projects in collaboration with NASA. People from different cities were pulled together into the same metaphysical space through the ‘hole in time’ and the way they responded was completely unrehearsed, as with how some of them even started to organise meetings with their family or friends.

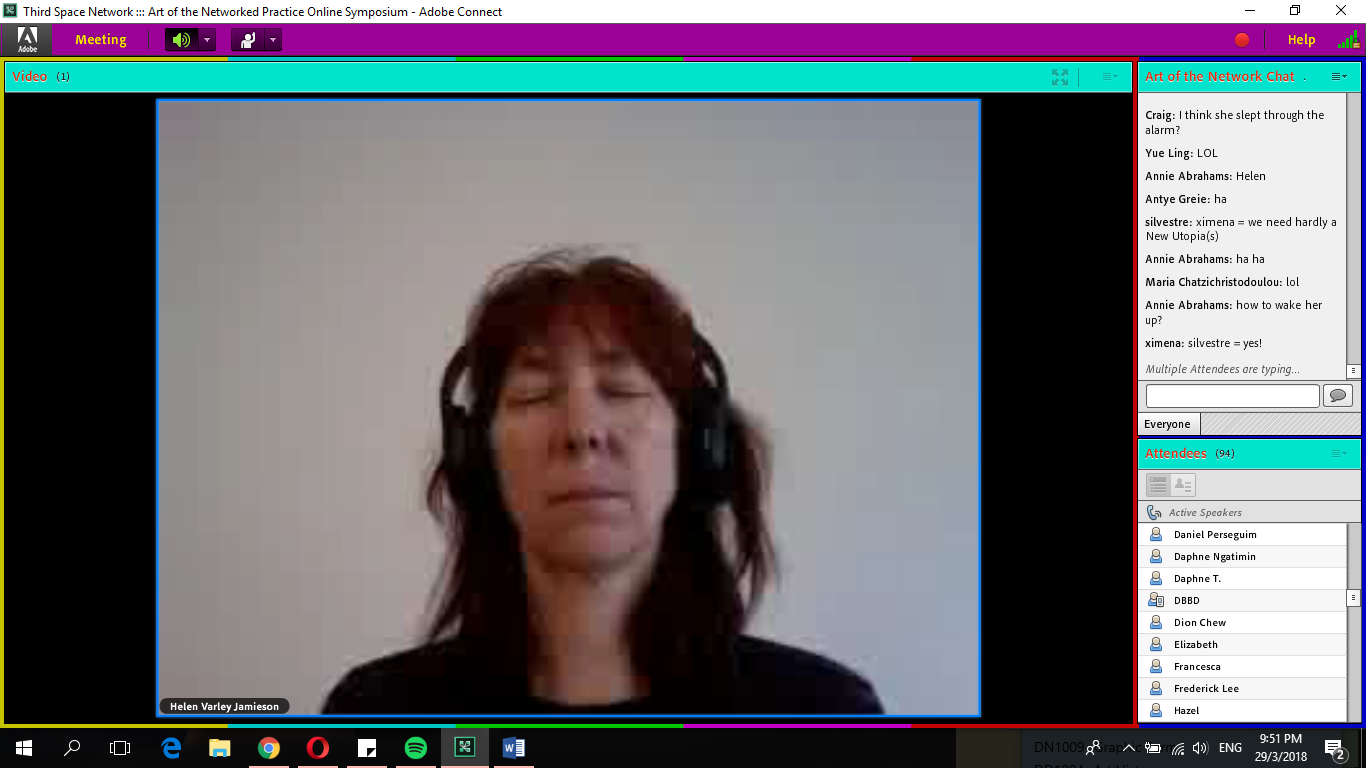

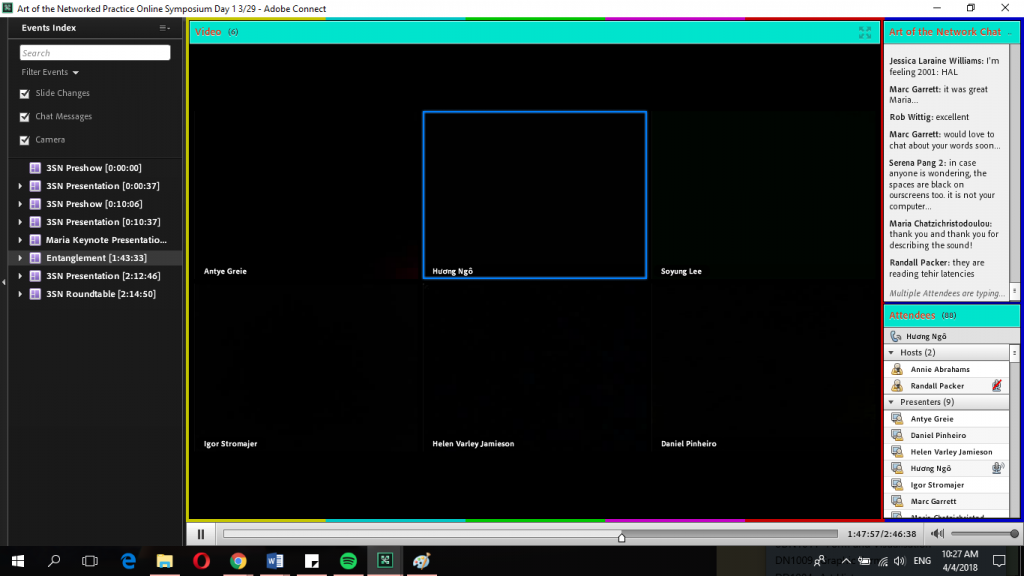

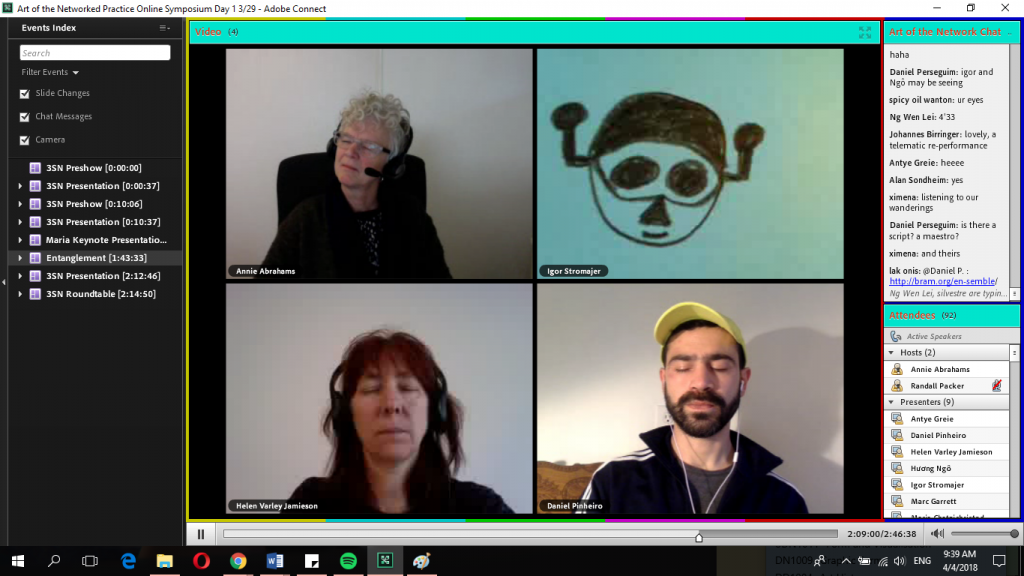

MariaX defined the interactivity of social broadcasting as ‘the performer being affected by the audience, and the audience affecting the performer’.Annie Abraham’s Entanglement Training performance was also a far cry from a passive delivery, rather, performers (some of which she has never met) were able to work alongside her.

In the case of the symposium, I was participating in the act of DIWO literally just by typing in the chatroom. The performers were able to interact with the online audience and this allowed for a collaborative act of helping each other understand the works and the intentions behind them. Essentially, this flattens out the hierarchy between performers and audiences and changes the way we perceive artists to work and interact with their audiences (contrary to the idea that artists worked in isolation in their own studio space).

Next, social broadcasting has changed the expectations of human interaction as new dynamics are introduced with this new medium.

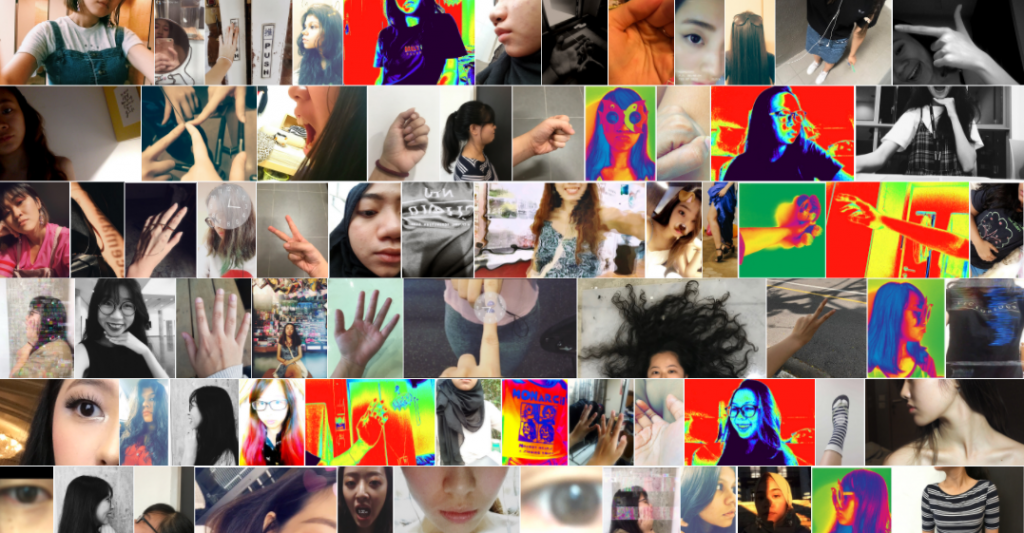

Social broadcasting nevertheless allows us to be hidden behind our screens in a safer environment that in real life where physical confrontation is a possibility. We discover this and over time, we find ourselves trying to paint the most ideal picture of ourselves online, trying to polish our ‘Digital Identity’, which is a re-imagination of ourselves, and our tele-presence projected into the ‘Third Space’.

In actual fact, the use of the Third Space encompasses the technical issues such as connection that come with it. To have the ‘Third Space’ in co-existence and seen in totality with the local and remote spaces would be to also accept the faults that comes with it, just like how we do not act in a perfectly rehearsed manner in real life, for that would be way too unnatural (the word in itself suggests that it is not characteristic of a living creature).

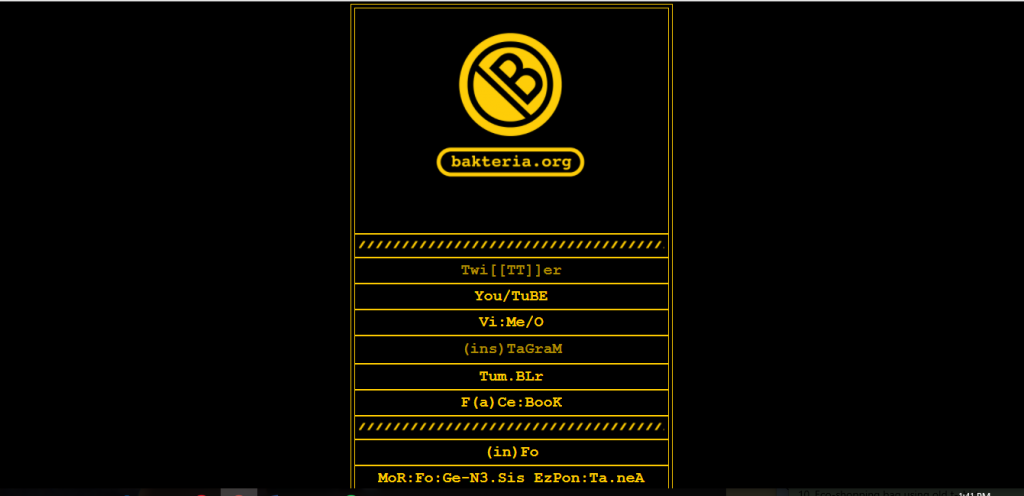

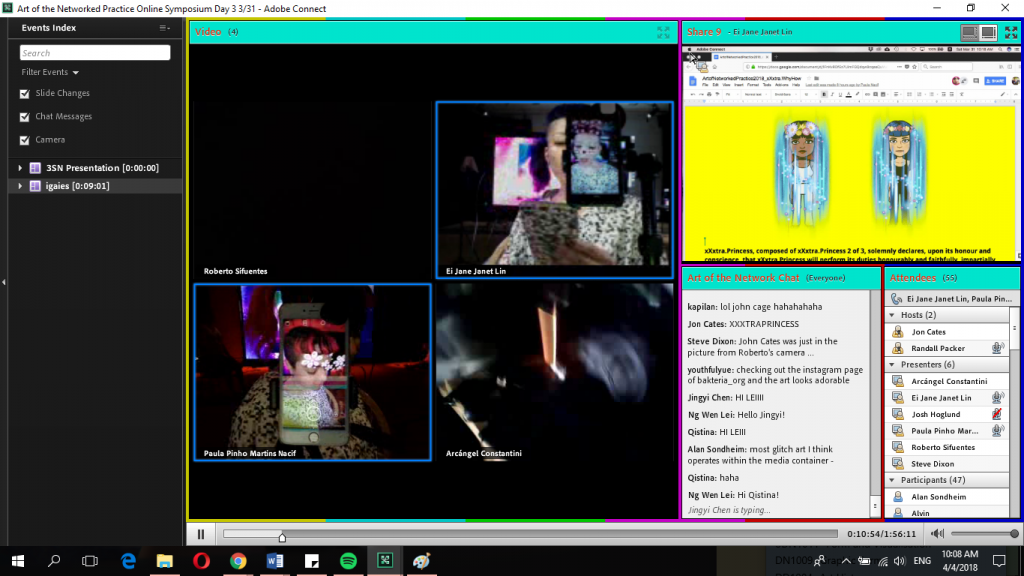

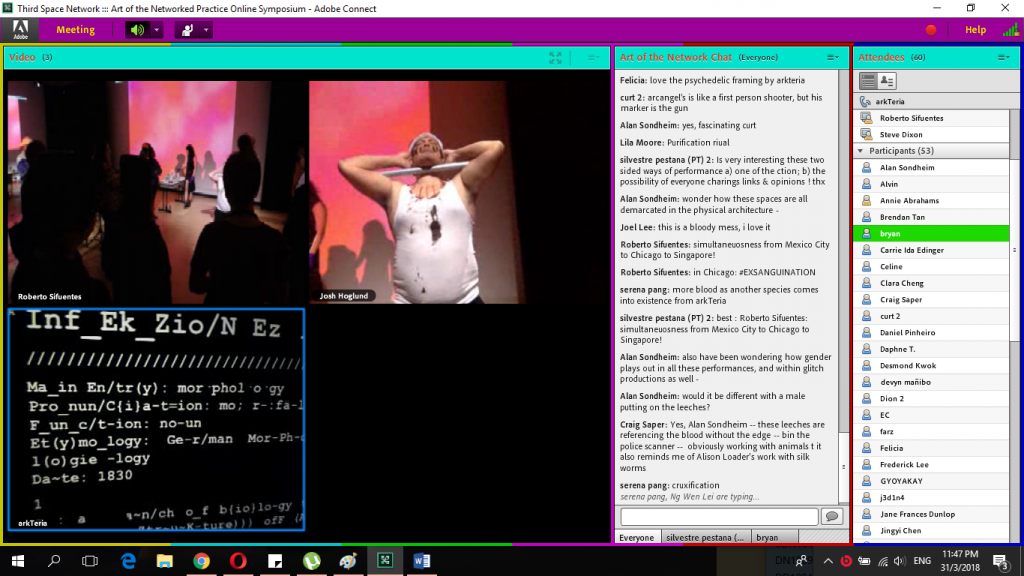

Arcangel Constantini also showcased one of his newest projects ‘bakteria.org’ that makes use of technical fault as a style, with the noise distortion soundscape and code glitch as a font type that gives rise to a unique and recognisable style. His little bacteria illustrations also represent how information is spread across the Third Space just like how bacteria spreads amongst people.

Annie Abraham’s works are quintessential to this very theme. In Entanglement Training – Ensemble, her co-performers followed her protocol to read out the latency in their connections, indicating how all of them are never really existing in the exact same moment in the Third Space, which may be a state which technology could ideally bring us to. However, she makes the latencies the very subject of her work and in turn explores the beauty of this imperfection of the medium to create a rhythmic, choreographic performance that really enchants the viewer.

“one millisecond”. “138”

“Excellent”

“Status”

“Connection status”

Annie Abrahams’ works are about the ‘sloppy’ side of people online and the intimacy between people. She likes to trap her co-performers in a state of ‘No Exit’ such that they are forced to expose their “messy and malleable” sides, prominent in her other works such as The Big Kiss and Angry Women. This shows how the digital medium is far from perfect and by making these faults the main subject of her works, we are continuous exposed to them and they are more normalised. In this way, we learn how to accept and embrace these imperfections more.

As the saying goes: ‘to err is human, to forgive is divine’. Then, following this train of thought, artists that work around the concept of the fault in human behaviour and technical glitches have already achieved a certain level of divinity. They have the power to change the way we anticipate the way our interactions online will proceed, and encourage us to embrace these imperfections as part of our newly established communication medium.

Last but not least, social broadcasting changes the way we want our new form of interaction to grow towards.

After being aware of these faults and learning how to embrace them, where do we go from there?

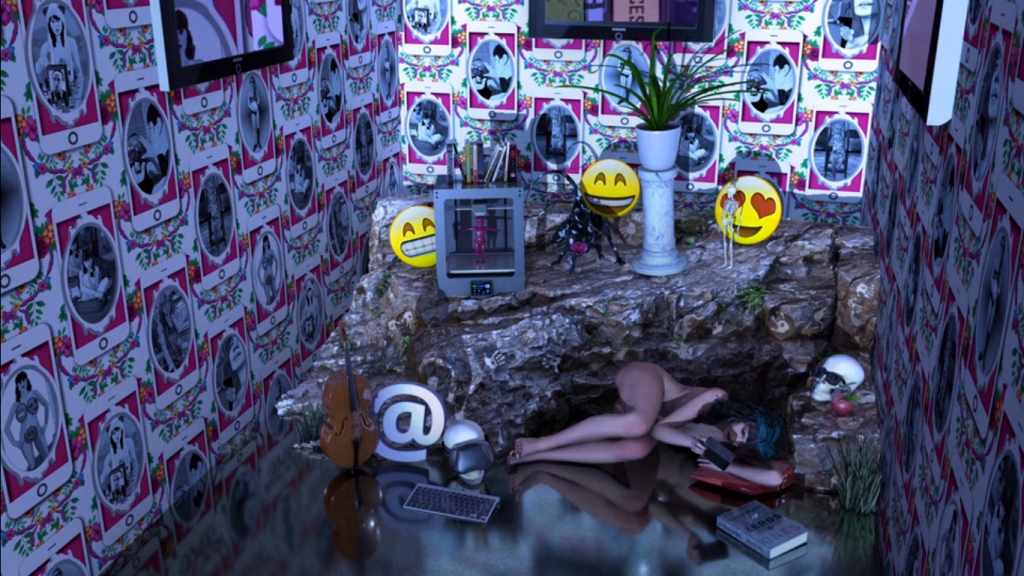

With a new world comes new laws to maintain some sort of order. New morals and ethics will arise and they will definitely be different from that of the real, physical world. MariaX brings up the issue of “Telematic Abuse” experienced by a performer where although her physical body was not abused, the abuse was directed towards a fictional existence of her real corporal body. How will we define laws that resist this sort of acts? Can they even be counted as legitimate abuse? These are definitely new questions that will arise as we continue to develop in telematic arts.

During the symposium, the ethics of respect was questioned when audience members were conversing in the chatroom while the performance was ongoing and apparently some people thought it was rude was others did not. Whereas, it is expected that people stay silent when watching a performance in real life since they are occupying the same space and may affect the performance.

#exsanguination, the audience members were discussing about the significance of the leeches in the performances.

Social broadcasting also gives people the ability immortalise a moment, as seen in from works like Ant Farm’s Blast Theory. This can be wielded as a tool to call for action by the wider public. We can see this in The Pixelated Revolution 2012 by Rabih Mroue, where a victim continues to film a sniper who is hunting him down and eventually shoots him. The very fact that he does not stop filming shows that he believes that the recorded video will be able to serve as a form of evidence later on. The way that we use this form of evidence is even prevalent today in court legislation.

Station House Opera also staged At Home in Gaza and London (2016) which also uses the technique of ‘dissolving’ to impose two images together to form a mutual performance space, where people could occupy each other’s’ homes, streets and social spaces, such that it focuses on the situation of people in Gaza, contrasting storytelling of Gaza versus theatre in America. This highlights the political isolation of people in Gaza and acts as a coping mechanism with the temporary relief of technology for them.

In conclusion, social broadcasting has revolutionised the way we communicate. It has changed our perception of interactivity, our expectations of interaction on this new medium and the direction where we want these new developments to head towards. Whether we like it or not, the ‘Third Space’ has already invaded and influenced our real world; whether we want to maintain its position as a partially isolated platform, separate entity, or continue to learn about it and embrace its faults to assimilate our physical world with the Third Space seamlessly is up to us to decide. We must continue to seriously consider the limitation of each form of interaction and find a way to strike a fine balance so that we can enjoy the best of all spaces.

Resources:

————–